Glass Road shows off the lighter side of Uwe Rosenberg’s repertoire

Most board game fans have heard of the legendary Uwe Rosenberg, however he is mostly famous for games like A Feast For Odin, Agricola and Patchwork, rather than some of his less well known titles — which happens to include Glass Road. As with almost all Uwe games, Glass Road is a reasonably thinky eurogame with a lot of tiles, resource and engine building features — but unlike most of his games, it uses a card-based action selection mechanism and a couple of roundels.

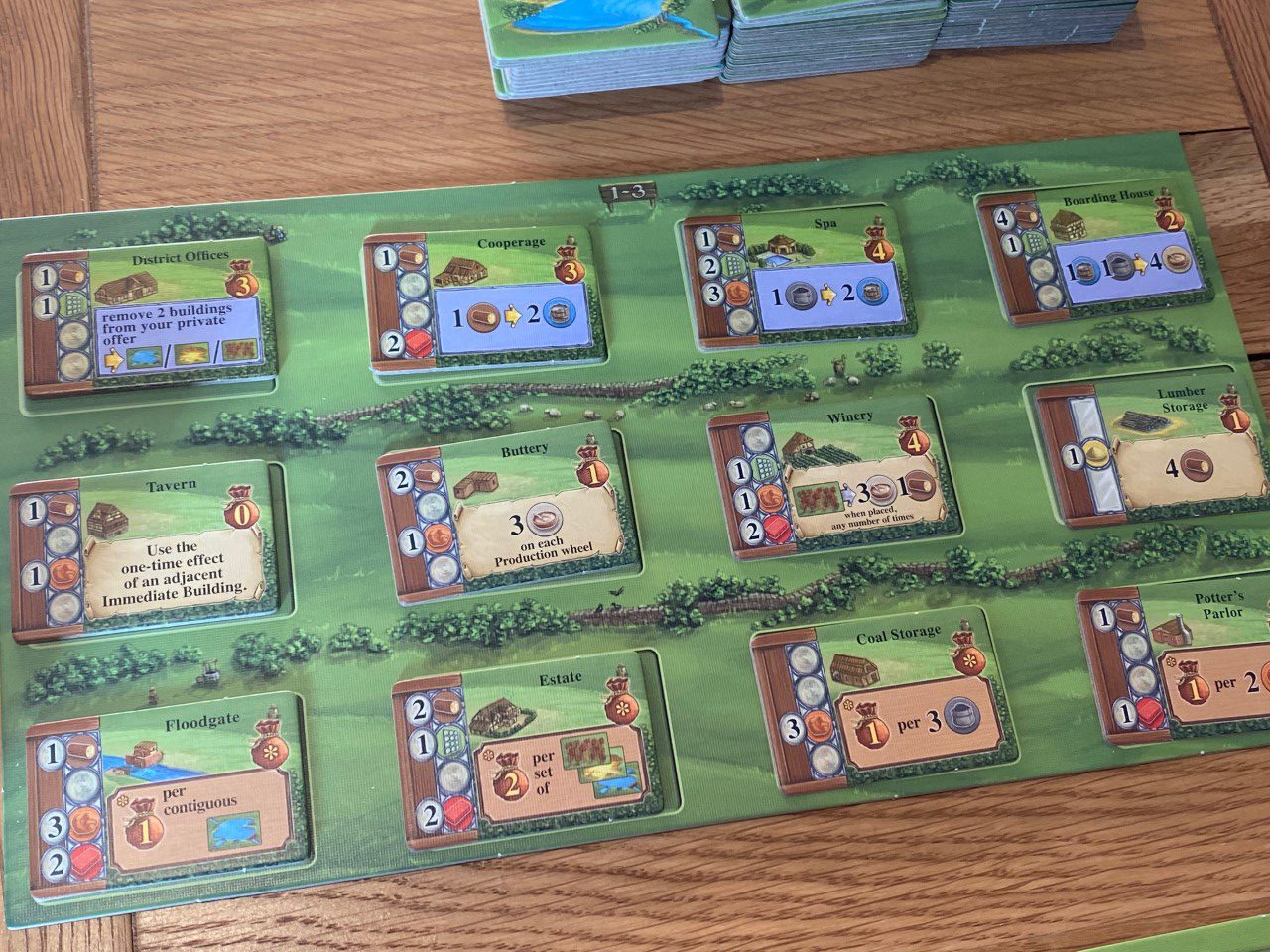

Thematically, Glass Road aims to recreate a period and place in German history where artisans gathered to make glass and brick along the German/Czechoslovakia border. The winner is not necessarily the best glassmaker (which is what I had expected), but rather it is the player who scores the most points across all of the building tiles on their own player mat — and this may or may not include glassmaking proficiency.

To produce glass and brick, players will have in front of them a pair of roundels which have a set of funny little fixed hands on them. One of these roundels shows how much glass a player has, with their glass marker trapped in the “smaller” space between the two hands. On the “larger” side of the hands, the player will find resources like water, charcoal, sand, food and wood. On the brick roundel, the setup is similar, but there are fewer resources — just clay, charcoal and food — on the larger side.

The relevance of the larger and smaller sides of the hands on these roundels is not immediately apparent. Simply put, though, if you look at the numbers in the centre of each roundel, you’ll see that each side tracks the amount of resource a player has in the opposite direction. When a player moves all of their “production” resources off zero, the roundel moves clockwise (up until it takes any one, or more, resources back to zero) and for each space it moves, it adds one glass or brick. So in short, as soon as you have at least one of each production resource on either roundel, you will produce glass or brick, like it or not.

But how do you produce resources? Well, that’s another big part of Glass Road. In a standard two to four player game, each player has their own set of fifteen worker cards — and all sets are the same. At the start of a round, each player chooses five worker cards to use and keeps them secret. Then, each player plays one worker at a time in turn. If a player plays a worker and no one else has that worker in their hand, that player can take both actions on the card. If one or more players have the same card as the one played, then each player must take just one action on that card.

This process then continues until all players have played all five of their cards (whether that be as a consequence of their own turns, or by copying another player.) After this the next round begins and the game continues until the fourth round of cards has been played. There are a couple of nuances that players should understand here, which are that in three or four player games, the “follow” action can (and must) be used if possible, but once two cards have been played in this way, any further potential duplicate cards are simply ignored and will then be played normally — this is to ensure that no player(s) fall too far behind due to losing half the value of too many of their cards.

One thing to note about this part of Glass Road is that it’s quite slow, and in particular with three or four unfamiliar players, it can slow things down a lot. With fifteen cards in hand, planning your own turn is difficult enough, let alone considering what cards your opponents may (or may not) want to play. Actions include all kinds of things and have various costs (some of which are free) and I found a lot of my games with new players involved either a lot of referring to the cards appendix, or with me helping people understand symbology.

That said, with just two players at the table, as a solo game, or with three or four experienced players, Glass Road runs very smoothly and actually comes across as one of the less opaque Rosenberg games. The worker card interaction is a key part of the game, and players often find themselves trying to work out how to optimise their decision both within the context of their own deck and player board, whilst also hoping not to land on the same card as one of their neighbours.

This actually leads to some interesting scenarios, and in most cases (the solo game aside, where cards have to be exhausted for one round before they can be used again) there are two or three ways to get a particular resource, clear a forest, or build a building, which does mean that considering opponents’ strategies is a valid thought stream. In most complete rounds of card play, a player will usually get enough actions to do all — or almost all — of what they want, but will usually have to think flexibly. Huge turns where everything goes to plan are rare, and I generally found that I enjoyed how well balanced Glass Road felt to play.

I did briefly mention a solo mode earlier, and whilst solo play is not really my thing, I would say that Glass Road does a good job of it. The latest printing includes a promotional “Harlequin” card which randomises the experience slightly (though no rules are included and you’ll have to go online to find them) and whether you play with that card or not, the experience is fun, quick and simple.

Whilst I wouldn’t say that Glass Road is up there with A Feast For Odin by any stretch of the imagination, it does take some of Uwe Rosenberg’s core concepts — production chains, simplicity, decent levels of player agency with some randomness – and delivers them in a compact and interesting way. The roundels are probably the stars of the show, but the worker cards (once you’ve learned them) and the buildings that are varied and capable of creating lots of different possibilities are also excellent mechanical additions to the formula.

You can find Glass Road on Amazon.

Comments are closed.