Ecos: First Continent — Populous Thinking

Ecos: First Continent is the second of John D. Clair’s designs that we’ve reviewed here at B3, with the first one, Mystic Vale, being a game that we enjoyed immensely thanks to its unique gameplay. Ecos, whilst having a completely unrelated theme and set of mechanics, is perhaps an even more individual design. With this game having sold out in minutes at the recent Essen Games Fair, we’ve been eager to see what all the fuss is about.

The aim of Ecos is to win the race to scoring either 60 or 80 points, depending on whether you want a short game, or a slightly longer one. Ecos supports up to six players out of the box, and how long it takes ranges between about 45 and 90 minutes, depending on the points total you’re aiming for and the number of players.

Each player will begin the game with a hand of twelve cards, usually comprising of one of the six prebuilt decks. Whilst it is a little opaque to new players at first, each of these decks has a different focus — such as land based predators, manipulation of the board spaces, populating the water, or simply on creating specific kinds of environmental situations.

The game also includes draft rules for experienced players that lead to a very different kind of game. Where the pre-built decks have specific starting cards, the draft mode requires players to have an understanding of what each card does (since there’s too much information to assess whilst actually drafting) and to work towards a specific plan.

Whilst not a good mode for beginners, this draft mode will lead to some seriously competitive high level play once more people understand how Ecos is played. You can also assume that drafting will add about twenty to thirty minutes on to any game as a minimum, depending clearly on the experience of the players and the number of them.

With nine of their cards in hand (and assuming you’re playing the normal variant) the players will have three starting cards on the table. A small number of Ecos‘ hexagonal map tiles will be placed onto the table, and the game will begin. One player will be chosen to lead the round by drawing thick wooden runes from a bag, each of which will show a single symbol such as grass, plants, animals, water or similar.

The players will also notice that they are each given a square piece of card with text on three of its edges, which will begin with the ‘start’ text facing the correct way up, as well as seven wooden cubes. When a rune is drawn from the bag, the players will assess the cards in front of them, and if one or more has a space on it that matches the rune that was drawn, then the player may cover that space with one of their cubes.

If a player chooses not to do so, or if they cannot, they will instead rotate their square onwards from the ‘start’ text. When the card reaches its third side, the player will be able to draw a new card from one of the two decks (red backed or blue backed) and then reset back to ‘start’. If the card reaches its fourth side, the player will be able to either play a card from their hand (there’s no cost for doing so) or take an additional wooden cube, again resetting their card.

Should a player choose to use the rune on one of the cards already played, they simply take a wooden cube from their supply and place it onto the matching space. If all spaces on that card are now covered, the card will activate and the player must call out “Ecos” which is always good fun when you’re playing in a crowded pub. If multiple players make the call, then each shout is resolved beginning with the player drawing runes and heading clockwise.

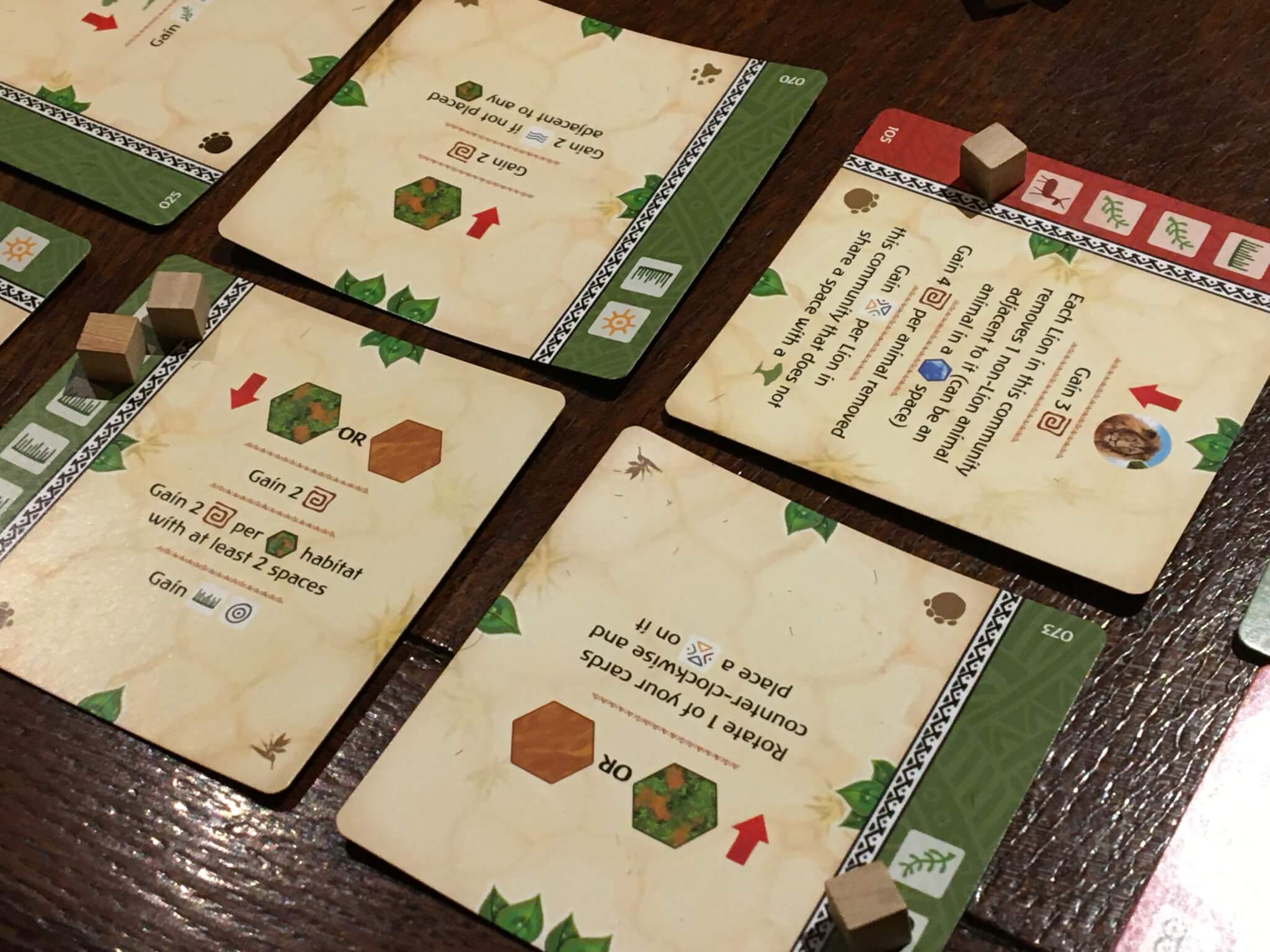

Resolving cards in this way is really the meat of Ecos, with combos chaining off each other being the goal of higher level play. Cards have a huge number of effects, and about two thirds of them focus on building up the terrain and affecting the animals there, whilst the remaining third allow players to fine tune their scoring. To put it another way, whenever a player draws a card, they’ll be choosing between a deck of cards that help them set up the world to their advantage, or in actually trying to capitalise on what has been built so far.

When I mention cards combining with each other, that’s because often, you’ll find cards that work exceptionally well together. Examples include cards that when completed allow the player to do something like place a desert space, then score two points, and then claim a wild rune (which can be used on any symbol) for each water tile adjacent to the desert that was placed.

In this example, let’s say that the desert tile was placed next to three water spaces, generating three wild runes. The player would then place those wild runes onto other cards, potentially triggering up to three more cards, which in turn generate their own actions, point scoring opportunities and perhaps even more runes. As each card is used, it is then rotated once until it has no leaves left on the side facing upwards — this means that it has been spent and must be discarded.

If we step back momentarily to the idea that the lead player is drawing runes from the bag, this will continue (even after someone shouts “Ecos”) until the wild rune is drawn, at which point any final shouts are resolved and then all runes are placed back into the bag. The bag then passes clockwise to the next player, who leads in the drawing of runes for the next round, again until the wild rune is produced.

Once one of the players reaches the point limit chosen at the beginning of the game (either 60 or 80) then the endgame is triggered, and the current round of bag pulling, plus one more will be completed. At this point, the game ends and whichever player has the most points, wins. It’s worth noting that triggering the endgame is by no means certain to indicate victory, since there may be ten runes or no runes drawn in the next round, before the next wild appears.

Ecos is a simple game to teach and the rules and structure are straightforward enough that even a relatively inexperienced board gamer can play it, but with that said, it ramps up to a high level of complexity very rapidly. With five, six or more cards on the table, each of which interacts with the others in some way or another, the need to analyse each move becomes considerable.

Add to this the real time nature in which each player reacts to a rune as it is drawn, and there’s no doubt that players will feel pressured into making decisions, which can lead to mistakes. There’s a temptation — and indeed a need — to use your wooden cubes judiciously, since having them tied up on cards means you’ll run out quickly. Activate cards in the wrong order, however, and you can seriously damage your point scoring potential, or even your long term prospects for scoring on future turns.

Ecos is the classic example of a game that is simple to learn, yet hard to master, but in this case the term doesn’t really go far enough. It’s simple to learn, tough to get to grips with from about halfway through your first three games until close, and then very challenging to truly master. What I mean by this last comment is — to play the game at full speed, and in particular to be competitive in the draft mode, you’ll need to know it inside out, and that simply takes time (or an exceptional brain.)

Even despite the slight health warning that comes with a game that leads to such potential for analysis paralysis and overall complexity, Ecos is the kind of fantastic new design that should be celebrated. Much as he did with Mystic Vale, John D. Clair has taken some common concepts (card management and tile placement in this case) and made a game that feels incredibly unique out of them. The environmental theme serves well to enhance the experience, and the AEG component quality, as always, is exceptional.

You can purchase Ecos: First Continent through 365games.

Love board games? Check out our list of the top board games we’ve reviewed.

Comments are closed.