Preview | Sengoku Jidai: Shadow of the Shogun.

Sengoku Jidai: Shadow of the Shogun.

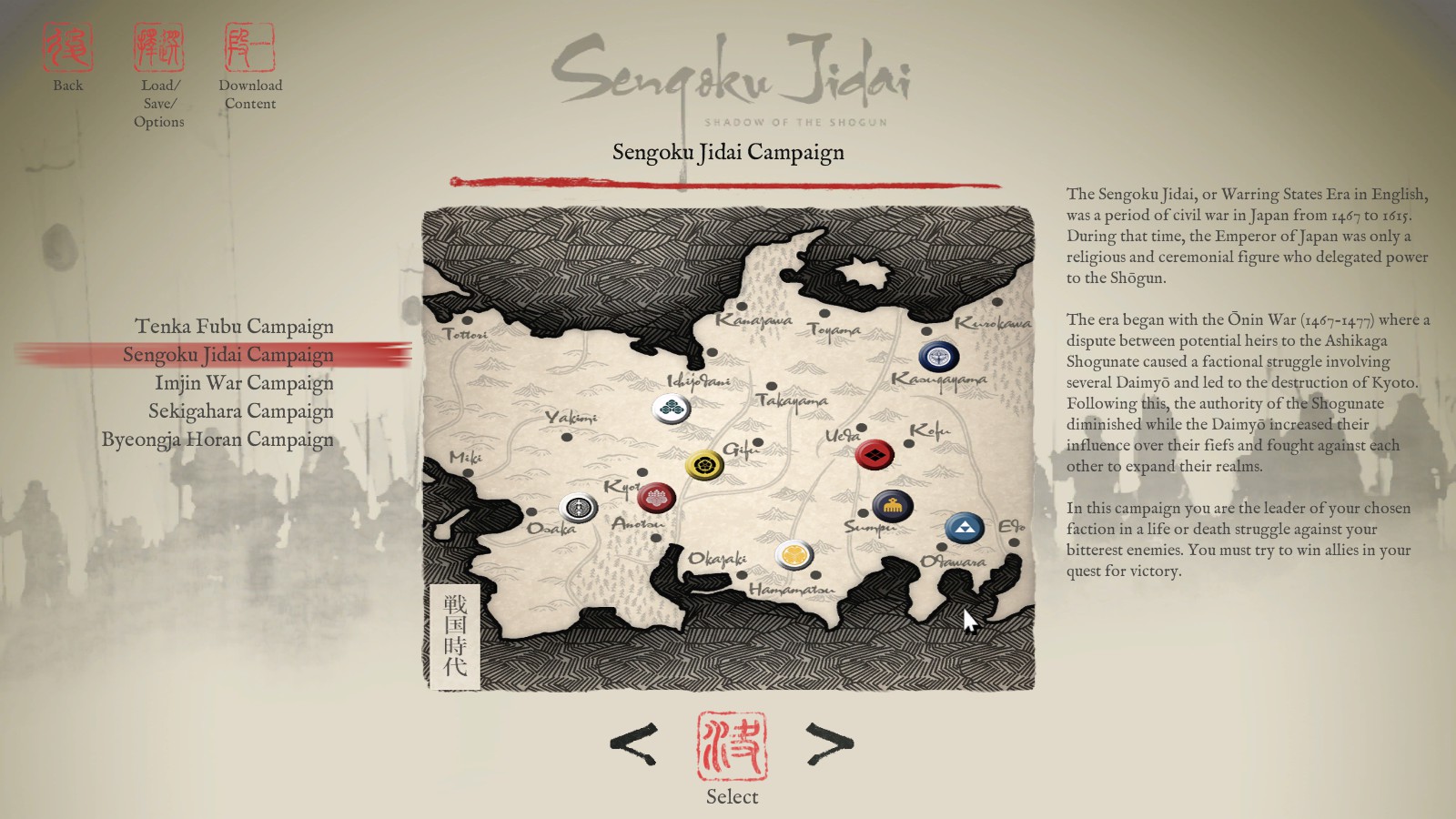

From the 15th until the early 17th century, Japan’s Shogunate was heavily contested by powerful lords from around the country. With both the rank of Emperor and Shogun, formerly with unchallengeable power, declined in their influence and control, the power and control of the nation became highly contested. The ruling lords, Diamyo, had grown stronger and began to question and challenge the leadership of the nation. This period, Sengoku Jidai – Age of Hostile Country – would go on to become one of the most renowned civil wars of human history.

“[The art is]…wonderfully inspired by the Japanese art of the time – it truly manages to penetrate every part of the game.”

Japan’s Diamyo were a ruling class of land owners who exerted military and taxation powers over those who lived and worked on their land – similar in nature to the Counts and Dukes of Feudal Europe. In the mid 1400’s war erupted over who would inherit the title of Shogun, the open conflict ravaged important areas of the country, and continued to do so until the combatants wore down each other to a hashed stalemate. During this time the Shogun, expected to enforce peace throughout the country, did nothing to end the struggles. With this other families took to war over land and power. Japan was, needless to say, tortured by this time. After this came a long period of conflicts as Diamyo rose and fell in power in attempts to take control of the puppet Shogunate and unite the land under their families leadership.

Critically, the period revolutionised not only the culture and agricultural technology of Japan, taking them from a middle-aged society into a more modern one, but it also massively changed the troop composition of the nation. Taking it from a nation where a lord might have 500 gunpowder weapons, to the united nation which invaded Korea with nearly 40’000 firearm wielding troops of their 160~k force.

As such, from the period alone, Sengoku Jidai: Shadow of the Shogun promised to be an interesting title, in the least for the degree of care and balance that would need to be taken as to correctly represent combat between horseback, spear-wielding, and firearm equipped troops.

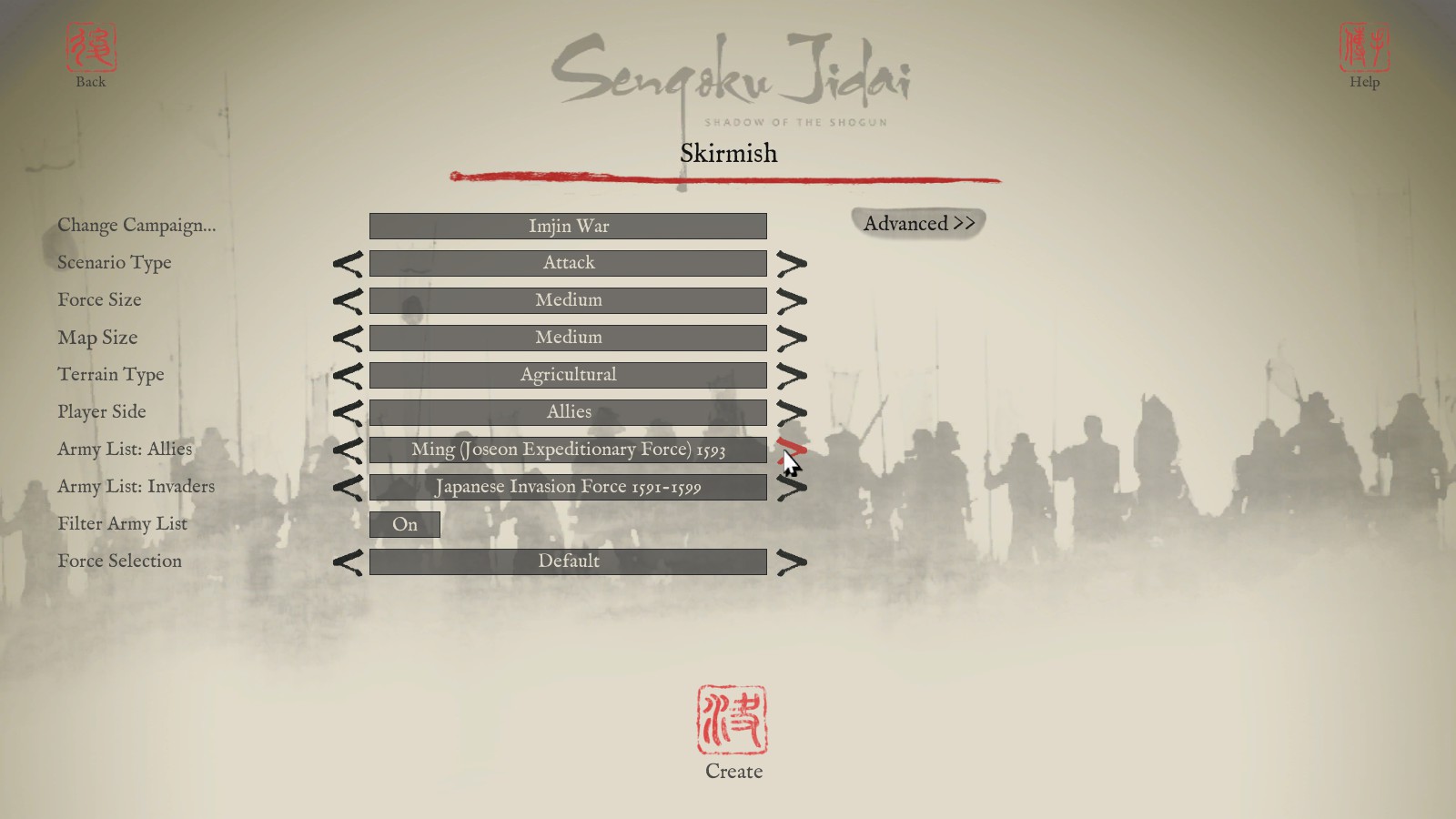

The Sengoku period gives ample opportunities for scenarios and skirmishes, and the game’s current selection of 23 historical clashes, and the free-form campaigns, gives a decent slice of some of the more interesting battles, it also allows you to play as either side of the conflict – which, as Japan doesn’t really change the composition up too much, however other nations of Eastern Asia are represented in the game, notably the Korean and Chinese forces, and great care has clearly been made to differentiate the various nations forces from one-another down from elite troops to militia.

Gameplay itself functions on a similar level to Byzantine Games’ last outing (due to the games sharing an engine) Pike and Shot, with the map being laid out in a tile/grid style over generated terrain, all rendered in rotatable and zoomable 3D. Much like Pike and Shot terrain elements like elevation, pathways, towns, and woodlands are clearly represented by the terrain, and troops clearly interact and react to these alterations in environs. Similar still is the composition of troops, being that the battlefield is similarly dominated by a mix of pike, shot and horseback combatants.

“…an enemy flanked by soldiers will wither and break without support”

The first, and most immediate, change is the artwork of the game. From troop artwork through to the menus, and terrain itself, the game is wonderfully inspired by the Japanese art of the time – it truly manages to penetrate every part of the game.

Combat, as with the more tactical titles from Slitherine’s catalogue, is to be carefully thought out. While the temptation when seeing neatly organised battalions is to simply charge the enemies having ensured that the second line can break through once the frontlines have softened up the enemies… that simply won’t work. This isn’t the rock-paper-scissors normally presented in the games which have covered the era, nor does it follow the conventions of the traditional strategy games which address the time frame’s European conflicts. While most games will simply throw 30 archers together as a squad, Sengoku Jidai presents you with a unit of 200+ units, assembled as a group of the time would have been – with, say, a front line of spearmen protecting the 150 archers behind, and even those archers being equipped with secondary weapons should they become locked in melee combat.

What this spells is a tactical game, more focused on positioning, flanking, and placement. Even a group of archers attacking in melee combat can be deadly should they catch a unit from behind – an enemy flanked by soldiers will wither and break without support, even if it is facing troops it would normally squash.

Due to the large numbers of troops which make up an individual unit, a face on conflict between any two units can take the entirety of a skirmish to resolve. This is where elements like elevation, concealment, terrain, and – new to the engine – Generals come into effects. In possibly one of the nearest emulations of Sun Tzu’s Art of War all of these play out with realistic effect, with swamplands and woodlands disorganising tighter formation troops into rabbles who cannot mount organised assaults from the terrain. Under pressure from forces, be that through witnessing the defeat of another unit, or through being surrounded, troops will break and disperse from the field – meaning that an effective counter offensive from just one troop late to the battle can have a domino effect shattering enemy combatants and giving much required time to re-form ranks to your troops.

As a matter of fact, while obviously missing the subterfuge and supplies of the masterwork, the game only really misses one of the major pieces of knowledge imparted from it – Position your men with no place to run. They will then face death without fleeing. In game troops afforded no room to rout will simply disperse rather than fighting to the last man. It’s, no doubt, a limit of the engine, and probably also best not implemented due to the morale – and skirmish length – implications.

With flanks so critically weak, and a rear assault fatal, the game involves a movement system which ties movement positioning to troop facings, and requires you manually turn troops during the turn. This seems a little arduous at first, and the fact a force cannot simply back up a tile while enemies are not approaching certainly seems harsh too. That said, for a unit to maintain a tight formation, and troops to hold morale, through and following a literal step back is exceptionally unlikely, however it would have been a nice addition in the absence of an undo button for moves, especially during the formative early turns wherein you either prepare for assault, or defence.

While your spears fight face the enemy, your archers loose arrows over the heads of the front line, your teppo shoot from the forest, and you manoeuvre your cavalry for a massive sideways charge – to crush enemies underfoot with the impact of the charge, there is another element to consider on the field. The Ally Generals.

Generals are a major game changer, the units under their command and within their sphere of influence will receive benefits from the proximity, being less likely to break, and likely to inflict higher damage. The generals are all named appropriate to their faction, and almost serve a hero role which is critical to remember. Unlike heroes however the generals are as squishy as their fellow soldiers, and when the unit they are attached to is engaged in combat they do tend to have a habit of rushing to the front lines, to lead with gusto and aplomb. Their influence in direct battle is somewhat extreme, while they’ll smash enemies and inspire the troops, they do rather have a habit of getting cut-up or shot – and that certainly doesn’t encourage the troops to keep fighting.

I mentioned the domino effect of collapsing morale earlier in regard to a neighbouring unit falling. Another interesting feature of the game is that troops locked in combat will automatically attempt to pursue and engage enemies they are overwhelming. While this can cause some issues – as no doubt with real combat – wherein pursuing forces will chase routed enemies from the battlefield, never to return. It can also create some wonderful breakthrough moments where you execute a perfect flanking charge with a fresh unit, with your unit shattering the enemy and then proceeding to do so with several others, all within one perfectly executed move.

Elements like above, come into play massively when it comes down to flushing enemies out from behind fortifications. An early tutorial featured a long line of archers behind a spike wall – troops charging to engage faced massacre, however a few carefully planned charges could easily shatter the defenders, allowing a gap large enough for your central column to penetrate.

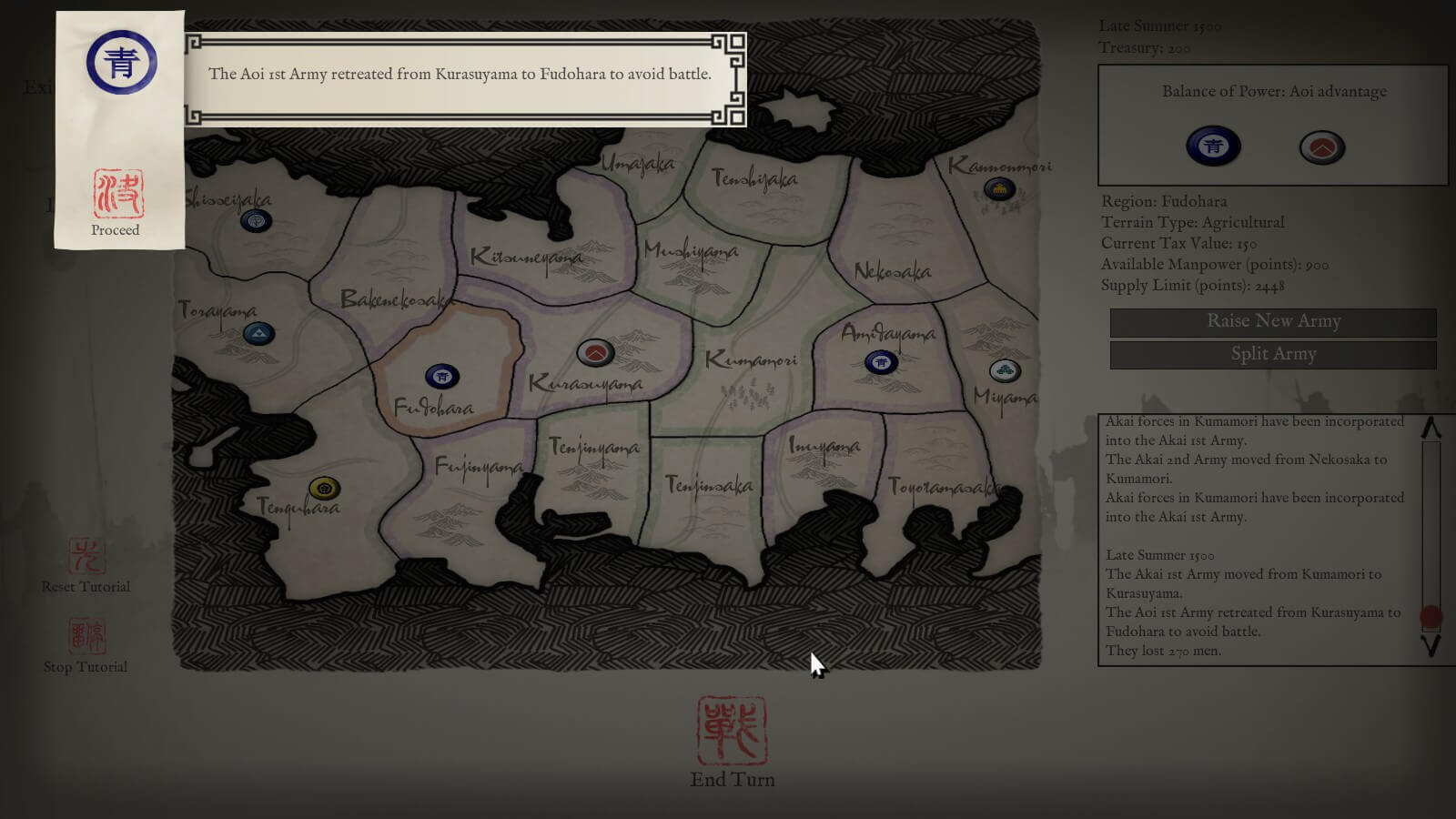

Combat itself is, understandably, a critical part of the game experience. However, it should definitely be noted that the game’s campaign modes actually include a slightly economical and overarching map screen. In these screens you move around your assembled forces – represented by various size tokens – capturing forts and, when the Season allows, recruit more forces based on your current economy. The forces involved in the campaign are all aiming for domination of their enemies through decimation, however outmatched troops will not engage in open battle, meaning that if you can navigate the territories of the map screen and keep your armies positioned where the enemies would not risk engagement you can ultimately force them back through sheer brute strength. Good luck with that, by the way, as with the combat AI the enemy is particularly alert to weaknesses in formation at this stage.

I’ve used the word skirmish three times to this point, however each have been in regards to a tight knit engagement. The game does, however, include a skirmish system that I’ve spent a little time with, it allows you to pick from any of the three major wars, from any of the factions involved and even pick from several specific compositions of troops as they were at certain times during the war. With these you can hold a quick, one-off, what-if-style battle against the AI or another player.

As I’m drawing to the end of this preview I feel I should really mention the fact that this game actually contains a completely functional, and well explained, tutorial which quickly covers most of the elements of the game, and explains the options hidden under the tools button – your means to visualise casualties, line of sight alter the camera or simply move to the next unused unit.

The build of the game that I’ve been playing for this preview is one exceptionally close to launch build, with the team currently in the final bug-squashing phase. As such we likely won’t publish a review for the release date of 19th of May, instead opting to revisit the game a short time after launch.

In conclusion, this is probably one of the most accessible, intuitive, and visually appealing turn-based tactics game that I’ve played over the last few years – and even though the game has a deep focus on positioning and flanks it’s all presented with such style that it almost transcends language. I’m extremely impressed with what I’ve seen so far, and I’m looking forward to any post-launch support it gets, as well as what the team do next.

Comments are closed.