Viewfinder brings a wonderful puzzle concept to life.

2019’s Superliminal had a really interesting idea for its puzzles, having you play with your perception of space to grow or shrink objects to allow you to progress. It doesn’t get mentioned much in spite of the creative concept, and it really didn’t have much in the way of imitators. This year we have Viewfinder, a game that also allows you to mess around with what you can see in reality, and totally refuses to get old over the course of its six-or-so hour story mode.

Speaking of story, there certainly is one in Viewfinder, but I found it to be terribly unclear. From what I could understand, you are searching a simulation to find a weather control machine needed to save the world from a dangerous climate. Much like real life I suppose. While you’re in there, you learn about the scientists and creatives that were in there working on the machine as well as other projects, and are loosely guided by an AI cat named Cait. Whilst the story does feel like it received a good chunk of the developer’s attention, I feel the storytelling itself was the weakest element of the game, being quite nebulous and often relegated to audio logs you could find.

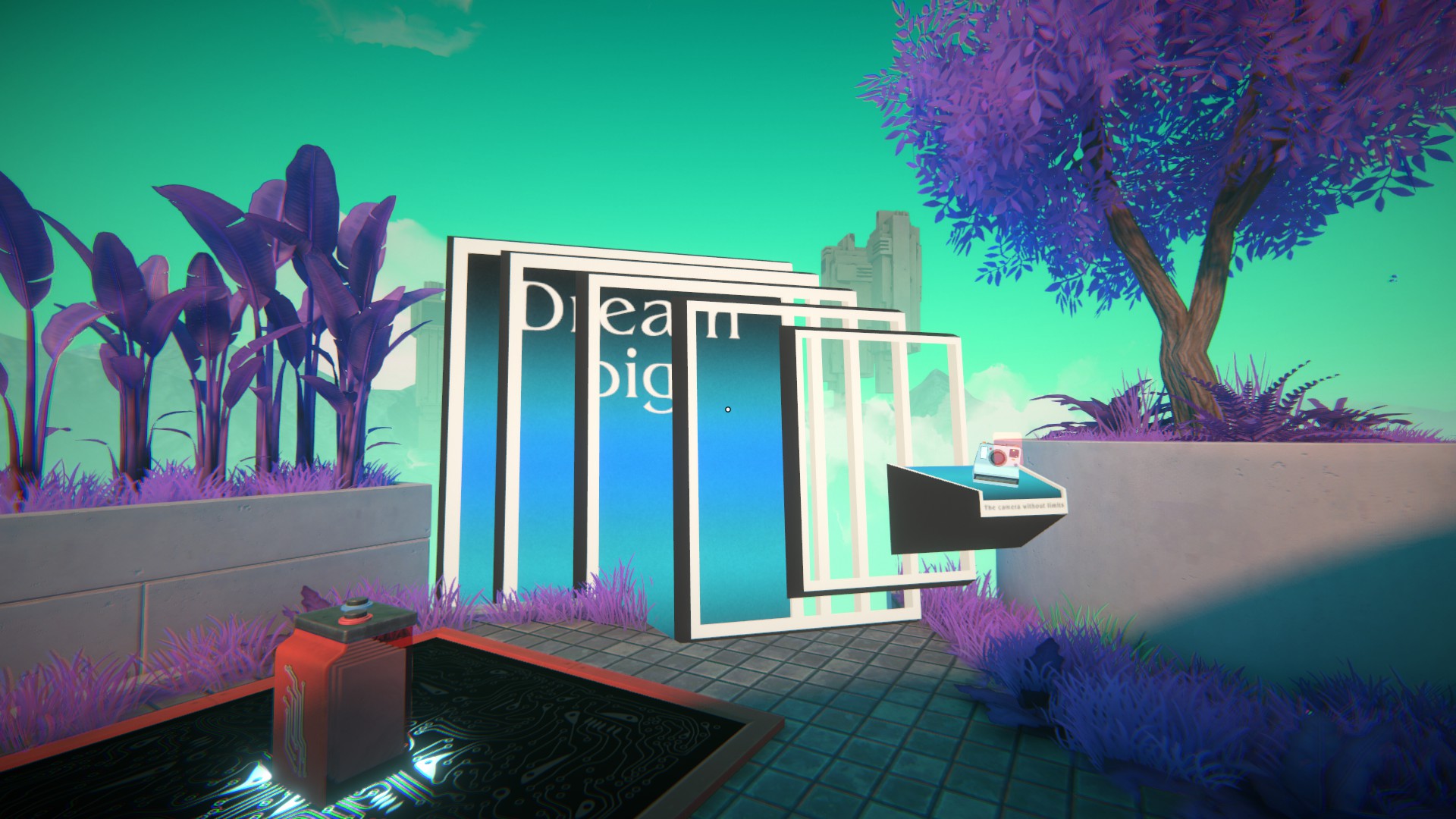

The world was terribly interesting though, reminding me somewhat of The Witness due to the bright colours and signs of life’s sudden disappearance. Everywhere you go you’ll see meals left unfinished, and half completed projects lying on tables. Cait occasionally makes vague references to the people who left these things behind but I quite liked exploring these spaces and seeing what else they were in the process of indulging in.

Although the story is weak, after the first few minutes of playing, I was far more interested in the gameplay itself. In each puzzle, you use photographs to manipulate the environment in order to reach a teleporter. By holding up a polaroid photo in front of you and clicking, that photo becomes part of the world. It’s hard to describe just how amazing this seems the first time you do it. When you click that mouse button, the photograph just looks like it’s still in front of you. Then you move to the side and realise its a fully 3D part of the environment that you can walk into and around. Equally fascinating is that the new parts of the world deletes the reality that was already there. As an idea, it’s a fairly simple concept, but I can’t begin to imagine how complicated this must be from a programming standpoint.

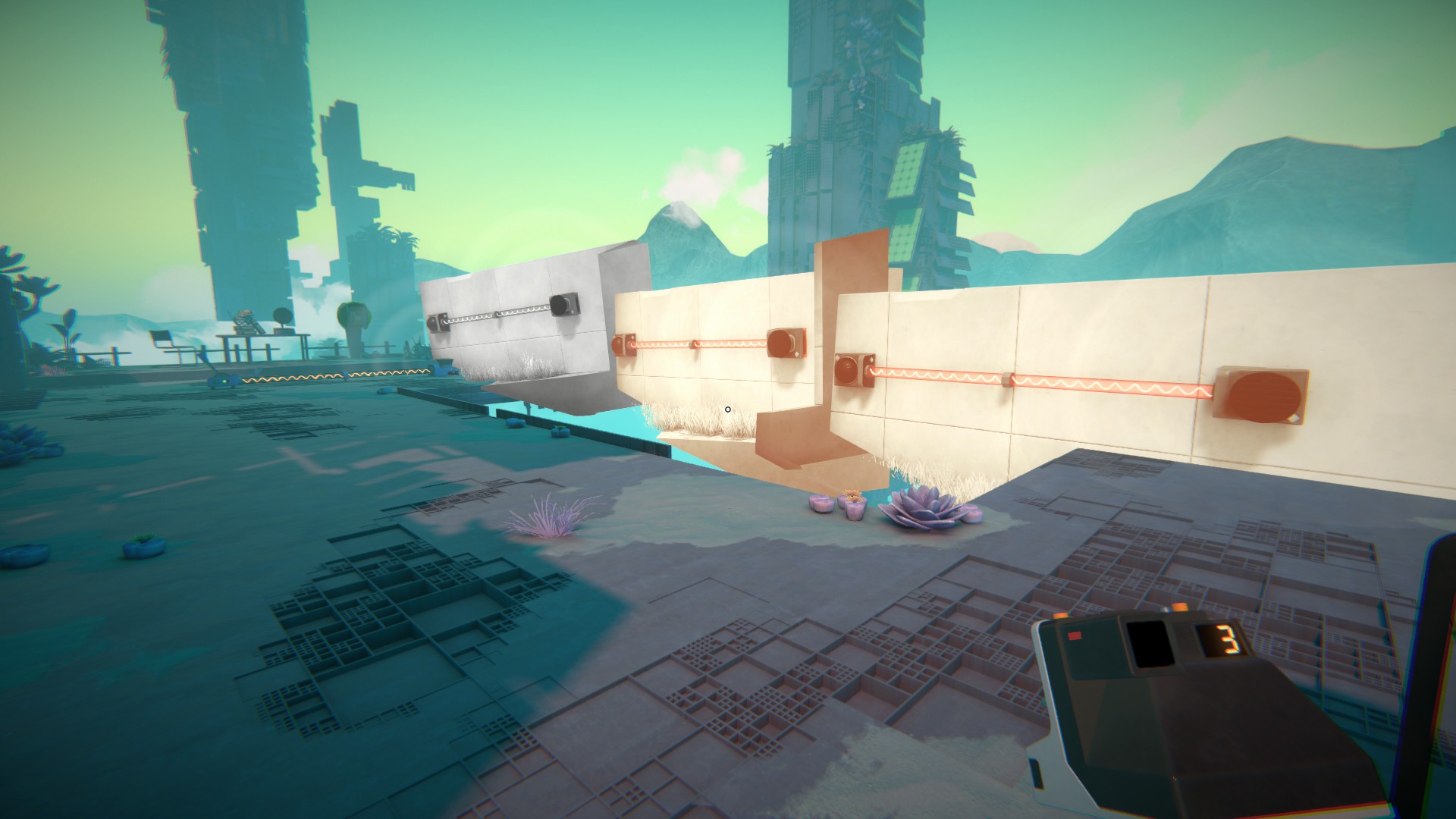

Initially, you’re limited to simply finding photos to use to open paths to move forward, but in each chapter you are introduced to new mechanics. Sometimes there will be preset cameras that you need to use to create your own photos, whilst other times will have you line up parts of a photo to create a new part of the world. These offer up some great tailored puzzles for you to solve, but Viewfinder is at its strongest when it gives you your own camera to use.

Having your own camera gives you a huge amount of creativity in solving the puzzles. Regardless of whether you’ve solved them in the “right” way, you’ll feel as though you came up with the solution all on your own and feel really smart when you do so. A good example of this is in a fairly simple puzzle that just wanted you to reach the teleporter on a high up platform. I found a flat part of the area, photographed it, and rotated the photo to create a ramp up to the exit. Then I let my 10-year-old have a go at the level without having seen it. She took what now seems like a more obvious approach of photographing a small staircase and positioning it to allow a route up. The opportunities for creativity are excellent, especially in the mid portion of the game where you have the most freedom.

Late in the game you lose a bit more of this freedom again sadly, but you do end up with significantly more devious puzzles. Certain elements of the environment, coloured in purple, cannot be photographed or be affected by photographs. This means that you have to find ways to work around them which really does limit what you can do. Still, these puzzles were really challenging, suddenly making something that was previously simple like crossing a chasm much harder. There’s a little hint system included which can offer advice on some of these puzzles though, which is nice.

As a technical showcase and a creative sandbox, Viewfinder is very impressive, and the developers have gone out of their way to create fun and interesting things to do in their world. I loved finding other images lying around that would allow you to do unexpected things. Some puzzles require you to manoeuvre speakers next to sensors to power the teleporter, but I found a picture of Munch’s The Scream, and when I placed it in the world it acted as a source of sound, activating the teleporter. You could even step into the painting itself. There are images of video game worlds you can use, and birthday cards that release balloons. I loved all this stuff as it felt joyful to explore and experience. Even the main menu presents itself as a digital camera display. Sad Owl Studios clearly put a lot of love into this, and I heartily recommend any fan of puzzle games gives this one a try. I doubt you’ll have played anything like it.

Viewfinder is available now on PC and PS5.

Comments are closed.