Have you ever dreamed about owning and operating your very own roller coaster? Of course you have! Well now, thanks to recent innovations in cardboard, you can. Coaster Park is a construction-and-dexterity–based tabletop game that pitches two to four budding entrepreneurs against each other in a battle to create and test the best roller coasters. The game features elements of bidding and light card drafting, but the real meat of gameplay is focused on the actual construction and testing elements.

Now, as a general rule of thumb, if I don’t have anything good to say I try not to say anything at all. Unfortunately, in my vocation as a reviewer, it is often necessary to level criticism at the games I play, whilst still trying to sift out any positives. I’m going to kick off by saying that I have had many enjoyable moments playing Coaster Park. It certainly generates a lot of conversation and out-of-game interaction, including guffaws of laughter, groans of disappointment and everything in between.

Unfortunately, whilst the construction (and especially the testing) of coasters can be really exciting, the supporting mechanics of bidding for components and specialist cards are clunky, nonsensical and feel tacked together at best. Each round begins with an active player who must choose a card from the central pool, then declare a price for it. Play then passes around the other players until someone either buys the part — or doesn’t. If they don’t, then the player who set the price must.

Given that the only fun bit in Coaster Park is the actual testing of roller coasters, there is a related rule that is quite odd here too. To test a coaster, any player who declines to purchase the piece currently being offered may instead pay a dollar (to the bank) to perform a single test. This feels very random to me and it really breaks up play in a jarring kind of way. Frankly, we often forgot that it was a rule at all and just threw a dollar in to perform a test at convenient times.

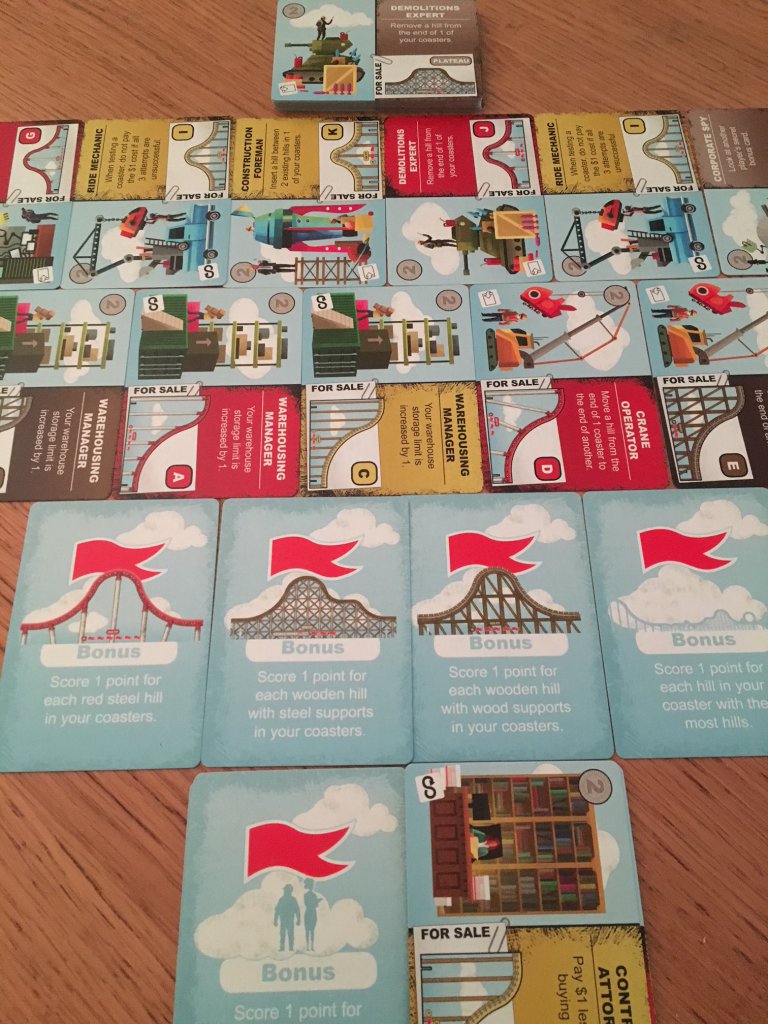

There are some other strange mechanics relating to the central store of cards. For example, each card represents both a track piece and a specialist that can enable certain actions, such as placing a track section between two that already exist. Before placing a track piece up for sale, the active player can simply buy an expert for two dollars. If they choose not to do so and do indeed place the piece up for sale at say, four dollars, then when someone else buys it, the active player can either take the four dollars from that player or choose to take any of the available experts and forfeit the four dollars.

Why would they do that, though, when they could have originally bought an expert for just two dollars? Why are all the players selling pieces of track from a shared pool they don’t own at all? It all feels so very strange and hard to decipher. Or to put it another way, it’s a very artificial construct to build around the core idea of construction and testing. It’s easy to throw stones, of course, but I can’t help thinking that there are several ways in which component and specialist selection could have been handled — a draft, a random draw etc.

There is a mechanism by which players can place their purchased cards face down in front of them in what is called their warehouse — it would make sense to introduce a sale mechanic here, but for the core flow of the game, it makes little sense. This would also support another anomalous component of the game, which is its overall economy. Basically, players begin with twenty-four dollars each, which dwindles every turn unless they can convince other people to buy the items they propose to sell from the central pool. By the late or end game, if no one buys your stuff and you end up raking in components you don’t want, it’s possible to have no money and next to nothing to do.

Let’s assume that your group can muddle through the elements of Coaster Park that sit outside the main construction element. The box contains a ton of cardboard pieces including launch hills, smaller humps, bumps and jumps, plus a handful of loops. Each section of track comes as a pair of cardboard pieces, which are then joined at two points by smaller crossbeams which sit between them. As you add new sections, you interlock them with the existing ones to form a continuous track. There are no corners to worry about, so aside from the loop sections (which are a nightmare) it all slots together nicely.

After all the cards have been dished out, players undertake final scoring, which involves rolling a marble down their roller coaster three times to see how far it goes. Points are then awarded for each consecutive section, with some worth more than others and bonuses awarded for various starting cards — for example having the most track pieces of a certain color. This is arguably the fun bit, although it is somewhat stymied by the fact that some players score nothing or very little, whilst others know the best combinations of track pieces and target them from the outset. Sometimes people are just lucky, whilst on other occasions the cardboard itself is your worst enemy.

Actually, on that note, I should mention that a huge part of succeeding in Coaster Park revolves around the precise way in which you angle your track pieces. This is, of course, why players can pay to test their tracks, but it can still be hugely frustrating to build an apparently sensible track only to be thwarted by some weird imperfection, or the fact that the cardboard pieces drag a certain way and require various tests to ensure they are eventually bent into the right shape.

I appreciate that this review is often critical despite me saying that the game has some amusing moments — and both of those things are true. My group did laugh a lot whilst playing Coaster Park, but we just never played it as it was intended at all, really. House rules were off the chain with this one, including allowing unlimited tests, card drafting and selling rather than the base system. Often, we just made the coasters we wanted and laughed at the results. As a result, whilst I feel that Coaster Park is kind of a fun thing to do, it is simply not a game I can recommend.

Comments are closed.