Preview | We Happy Few

We Happy Few from Compulsion Games (Contrast) is to the 1960’s what Bioshock was to the 1940’s – a divergent, broken world, set a’spiralling by tragic events, until one day it began to collapse itself, and took a turn for the twisted.

In the case of Bioshock, Ryan’s ambitions were triggered by the nuclear bombs that rapidly ended WWII; his secret idealist society fell to greed and curiosity. We Happy Few’s Wellington Wells War ended with Britain occupied, the country in ruins. It’s turn for the twisted was in what the town’s folk had contributed to the Nazi force’s fight against the Eastern front; something dark and sinister. Wellington’s people were torn, the wastrels cast into the ruins to live in a spiralling depression, branded as downers. Meanwhile, in the city itself the sixties notorious penchant for psychedelic colours and drugs shone through even brighter than it had in reality, however the Wellies get their kicks from a drug called Joy, a tablet which eases forgetfulness, and opens the mind more so to suggestion. It also masks bitter truths with brighter, happier alternatives – stay on Joy and you will become ignorant to the real world, and ignorance is bliss.

Maybe I am wrong to instantly go for the Bioshock comparison. The games do share a lot of similarities in regards to the dystopian setting, and the tightly scripted prologue for the currently included character -Arthur Hastings- is certainly also reminiscent. But, and it’s a big but, contrary to the speculation of those who only heard about the game first with it’s E3 trailer (which was in fact just a play of the previously mentioned prologue) the game is actually a lot more free-form, and unforgiving, than Irrational Games’ 2007 title.

It’s actually a survival, social-stealth (more on that later), story-driven game with procedurally generated districts. Each district, from the starting ruins through a plague ridden district into Wellington’s main city hub, are each jumbled up and shaken around with each new character start, keeping the same side-missions and gateway quests, but moving connections and locations around on each re-do. With more and more games going for procedural layouts it’s becoming increasingly less needed to explain the concept. It’s definitely worth mentioning in the case of We Happy Few though, as the game does it so well; if the starting hub wasn’t arranged into blocks, rather than Hamlyn’s long winding streets, then it would be hard to imagine where two chunks connect. In fact, the giveaway clues, the over generous distribution of those British cultural icons The Red Phone-box and The Red Postbox, could easily be signed off as an attempt by the developers to pump the game to the brim with these hallmarks, as opposed to a programming loop. I know that you don’t find a postbox on every street, but maybe that shouldn’t bother me as much as it does.

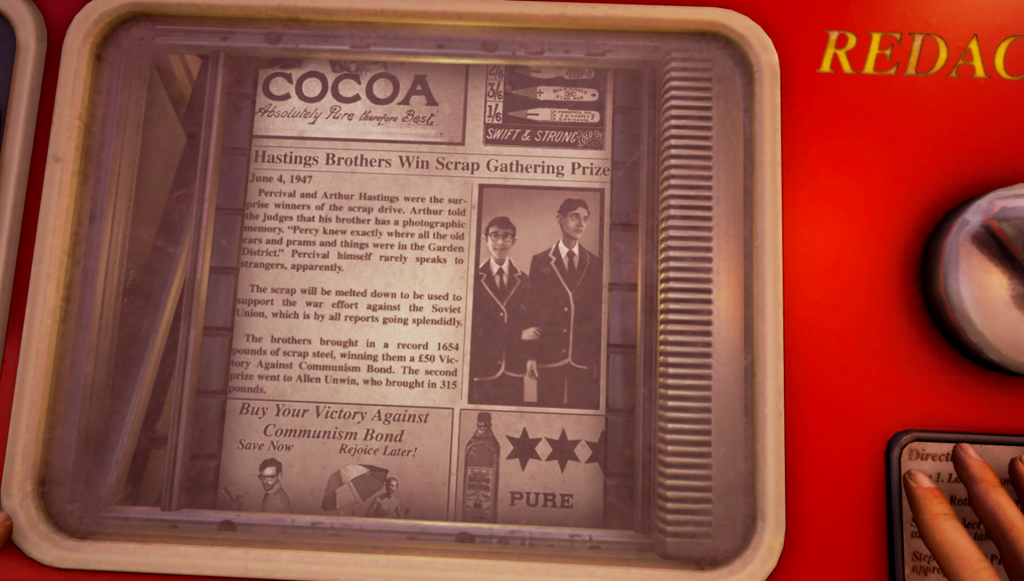

The thing with a world where forgetfulness is king, especially one with a really intriguing alternate reality setting, it doesn’t actually give up much in the way of information on it’s own history. That’s likely just where I’ve only penetrated three of the settings deep into Arthur’s story, but then the fault also might be with the very same Mr Hastings; whose job in redacting newspapers gives us brief windows into history, the nature of his job, but also no context for the stories we are seeing. Returning to my recordings of my first play through the game where I had fully explored the prologue section of the game, I noticed that the first newspaper article approved during the gameplay is an article from 1945 telling of a garden show winner stealing the show with a depiction of the Nazi flag alongside Britain’s Jack; telling that the two were one nation, or at least heavily allied. Other clippings, especially the adverts in the paper tell of the united fight back against the USSR; specifically when the protagonists memories are jostled by an image of his brother from when they won a scrap search through the ruined districts to help in the fight against the red menace – he is shaken by the sounds of a train leaving a station, and the brothers shouting to each other. There’s no doubt more story to be told through characters yet to be added, and through the other two playable characters set to join Arthur in the full release – after-all, Wellington’s drug addiction comes from a want to forget the atrocities that the island-city committed in order to remain intact while Britain was laid to waste by the Nazi occupying forces in 1933 [from the game’s Kickstarter page].

“Located in the southwest of England in 1964, Wellington Wells is a city haunted by the ghosts of its recent past. In 1933, this world deviated from our own, and the Germans successfully invaded and occupied England during World War 2. Most of England is rubble, as is a fair part of Wellington Wells. However, during the Occupation, the Wellies all had to do A Very Bad Thing. To calm their anguish and guilt – and forget what they’d done – the Wellies invented Joy, the miracle happiness drug, that obviously has no side effects whatsoever.” – Kickstarter page.

I’m genuinely intrigued about the setting; I want to know if the depths of the deviation, and the details just don’t seem to be freely available – if you google search the game you’ll find several videos (for one example, add ‘Yogscast’ to the search) which have descriptions stating that the “A Very Bad Thing” which was rended, was rend against invading Soviets, while other sites replace the Ruskies with the Nazis. Both parties play large roles in the game world’s current point of origin – but at the moment the history has major pockets of blanks – I sincerely hope to find out what said Thing was. And, what of Wellington Wells itself? Wellington is a city near Taunton in the Southwest of England, so could certainly be linked, however I personally reckon we have a situation more like Guernsey & Jersey’s occupation during the war, the nearest point the Axis came to taking British soil historically. Is the secret related to why the rest of the country is said to be in ruins? A paper dated 1959 says about the Avon (nr Bristol) being deemed safe to swim in by a minister; inferring there is still a government out there, and Joy itself was first tested in 1952 by another newspapers reckoning, and tested centrally at that. Could it simply be the obvious cannibalism that V-Meat (Victory Meat) and Strange Meat slaps into the players face whenever it’s mentioned? If there is anything I can say about the setting, it is completely intriguing.

There’s a few oddities in the setting, much further than the retrofuturistic technology and magical plants that now dot the English countryside. If the divergent point was 1933, then why is Churchill on posters? At the time he was simply a back-bencher representing sunny Epping. In fact Macdonald was still the prime minster of the United Kingdom, having not given the mantle to Chamberlain yet, and Maccy-Dee wasn’t keen on giving up a cabinet seat to Churchill despite him holding charge of several critical positions in the previous conflict. The only logical counter to this is that he became some head of a rebellion, but that seems unlikely due to the timeframe of the other news pieces. Another odd thing is a few anachronistic sentences, the most notable of which is -as Arthur lays down his head to rest- “It’s been a hard day’s night” a clear reference to the Ringoism that went on to be the name of a song, and a feature film of The Beatles. The divergent point was three decades before the quote found it’s way into the lexicon, and the chance of The Beatles being around, and influential, at the time when looking at the state of Wellington Wells… it’s close to nil. It sticks out something abrupt and certainly certainly – like the plethora of post boxes – calls the setting into question a little.

“…I am genuinely curious about the setting, and the great evil act that was committed by the townsfolk.”

Arthur’s prologue -the abrupt appearance of a memory shattering maybe a decade of conditioning- ends with him in a small subterranean hideout, this serves as your tutorial beyond the movement, looking and interaction of moving through the redaction department. You’ll learn to craft and use a lockpick, learn the odd inventory interface, and -assuming you pay more attention to the body dangling down the corridor than I did- find out a way to get free of the island, to a land probably just as deadly, but not as on-the-cusp-of-a-collapse as the various districts that remain of Wellington Wells.

For those who only saw the E3 trailer of the game before playing, here’s where the differences will almost immediately set in. For a start, as you stand there watching and absorbing Uncle Jack’s words of wisdom, to batter and report those who try to get you down, to always take your Joy and take part in group activities, and to not go out at night; it becomes immediately obvious that time plays it’s part in the game. Head outside and the world is as pretty and well rendered as the prologue, but shortly after Arthur’s emergence the game’s moodles start ticking, and soon you’ll be told you are thirsty, hungry, and tired.

The game’s survival traits are immediately present from that point, creeping down, further exacerbated by certain items you might use to cure them; sickness comes from eating rotten food, plague comes from a variety of sources, thirst comes from most food, and tiredness comes from standing around consuming various things to cure your ailments and thirst. At the start it is, undeniably, a complete hog of your time; it is in fact only through several retries or respawns (if you play with permadeath off) that you’ll learn how far you can push yourself, and what you need to be equipped with when you head out of safer areas into riskier territory.

The ruins, the garden district, and Hamlyn, the three of the five sections of the game currently included, are all fully realised within the game, and they look great. Each of the various pieces that fall together to build up the relevant districts look, and match up, perfect. The missions that overlay some of them certainly don’t however.. The later stages of the existing game require you to -for a mission that I don’t know where you get it- switch some of the Spankers, a tesla-coil (for the Red Alert fans) style electric pylon that shocks the downers over as to make it shock the Joy laced citizens. I still don’t know the giver of that mission, nor do I know who Inspector Hogarth is, even though my character remarked on them after I found an item I had three or four of within my inventory. It’s easy to appreciate the game is in early access, but Hamlyn’s mission switches and triggers seem slightly off which is a major shame as it’s a complete change of pace from the other regions of the game.

“The water in Hamlyn is laced with Joy however…”

Hamlyn’s people, as I mentioned earlier, are laced to the teeth on Joy. It’s the third district – and final one of the alpha – that you’ll find yourself in after skirting around the first two impoverished districts on fetch quests which ensure you spend some time exploring and familiarising yourself with the crafting systems and mood-juggling required. One introduces you to the effects that clothing has on your interaction with the environment; some make you hardier, others simply make you fit in with the citizens in each area, rags, tidy suits, posh suits, and workers overalls. Another of the quests asks you to -and it turns out, it’s either- repair a pipeline after saving a chap from joyed up wastrels or sneak past -or knock out- some bobbies (police for the uninformed) as to get their keycard.

Indeed, the ruined regions each have their role in training you. The first teaches you to scavenge, almost everything can be looted (although strangely not all cupboards, or drawers) including the big piles of rubble in the street. Those piles contain empty bottles, screws, metal scraps, rotting food, and a whole lot more. Crafting recipes don’t currently come thick and fast, although I suspect there’s plenty more to come in the full game. I ended up having to return to my safehouse to try and combine up the various items I had stashed away with the stuff I had been carrying as to simply free up some space in my inventory – the game doesn’t make it quite clear enough the full scope of the recipes – should I hold on to the empty pill pots for some later purpose, do I need rubber ducks, or old syringes, or rags? It doesn’t help that the inventory system is using a grid system reminiscent of Arcanum, or Resident Evil, wherein you have to fit the items into the space, things only stack to certain degrees (only five lockpicks in a pile), and there’s no sort function on it. With these quirks it’s easy to start ignoring components, and only heading out from base-camp with the bare survival items required.

The second area introduces new traps, explosives, and also features more tight, secure areas which require you to skirt around carefully. There’s more missions that focus on home invasions too, further still certain citizens here are infected so you have to keep your range. Most importantly, the aforementioned Bobbies are present here, guarding a tree. Much like the people of Hamlyn they are immediately suspicious of any downers, and will attack you if they think you are up to no good. If you haven’t toyed with Joy by this point then this is the introduction – the darkness peels back, rainbows dance across the sky, the contrast flies up, your character throws his hands forward as he walks. His interactions switch from dreary lunacy or poetic depressions into chipper greetings and happy rhetoric. Arthur’s cheery chatter is enough to get him in close, to get the required keycard, and then spirit away.

From there the game steps up massively, once you are in Hamlyn the various mechanics click in to place. While the previous sections gave ample time to learn about the negative affects of certain items; rotten food can cause sickness which rapidly builds thirst, Joy withdrawal is abrupt and messes with the moodles, tiredness is inevitable and the required rest will normally crank up your hunger and thirst; They also touched on the requirement to juggle actual stealth, moving on the outside of town, looking before you leap; They also introduced social stealth, hiding in plain sight. Arguably, by this point there are so many habits and techniques running at once that it’s actually almost a thrill to make your way around the bright and cheery town. In Hamlyn main roads are painted bright colours, villagers jump in puddles and play patty-cake in the streets; they play in the parks, underlining the absence of children in the game’s setting. Shops are open for business here too giving you a place to get items without having to scavenge through piles of waste in the ruins.

The water in Hamlyn is laced with Joy however, and so if you didn’t bring in pure water from outside you’ll be forcing yourself to hole up in buildings as to nap in citizen’s beds because if the Joy chemicals build up too strong in your blood you get hooked again, and simply wander off to return to your job, losing the game instantly. That is the new balance you are required to manage here. That said though, food is much more freely available in the village, every house has a kitchen with head-height and waist-height cupboards – that alone means that you’ll find more food and useful items in a single house than you would in five or six ruined ones.

There’s a massive amount to enjoy about We Happy Few, even if you came to it with only experience of the E3 trailer. Yes, the survival elements do feel a little too rapid when first introduced, but by the time you reach Hamlyn -the midpoint of Arthur’s journey in the final game- it’s clear that those are required to add momentum to the game, which are procedural layout isn’t ideal for. Especially as the story elements are, simply, not timing focused or really, even directional. You could spend real world days just looping around the starting area achieving nothing, with no inclination of where you need to go until you open your map or journal, the moodles give you the need to reach further out. Would a mode without them work? Certainly, if the navigation features are improved, more icons on the hub including a marker towards critical missions, and a time frame to finish the game within.

So, I will definitely be playing more of We Happy Few as the game develops, and it gets closer to release. Mainly because I am genuinely curious about the setting, and the great evil act that was committed by the townsfolk – I suspect something to do with children, sterility, and the curious fog that seeps out at night time.

We Happy Few is set to launch after about six months further of development.

Comments are closed.