Lords of Hellas review – The stuff of legends

![Lords of Hellas]()

- As a fan of both board games and all things a little bit geeky, I must admit that I’m also a fan of robots and Ancient Greek mythology. I can’t imagine what would happen if someone spliced all of those together – but wait; yes I can, because thanks to the team at Awaken Realms, Lords of Hellas does exactly that.

Overview

Set in alternate time and place, one where Zeus, Hermès and Athena (in the base game at least) preside over the realm of man, Lords of Hellas is area control at its very, very finest. I’m not even going to try and hide my excitement, because even though it’s only July, I think this game might well be in one or more of my top five lists for the year. I’ve learned over the past years that I have a natural tendency towards so called “dudes on a map” type games, but I think this is my favourite even among the genre, surpassing even the exceptional Cry Havoc.

The game features four heroes to choose from and supports up to four players, with a surprisingly deep solo campaign that offers a complete campaign to work through. When played multiplayer, the game is really designed to host all four players and there are some minor changes for lesser player counts. To save all the hassle of explaining these changes, I’ll focus on playing the game with a full quota and the very different solo game. I’ll also mention that there are already numerous expansions available for Lords of Hellas, from additional god statues to terrain upgrades, but I have none of those, so this review concerns the base game only.

Components

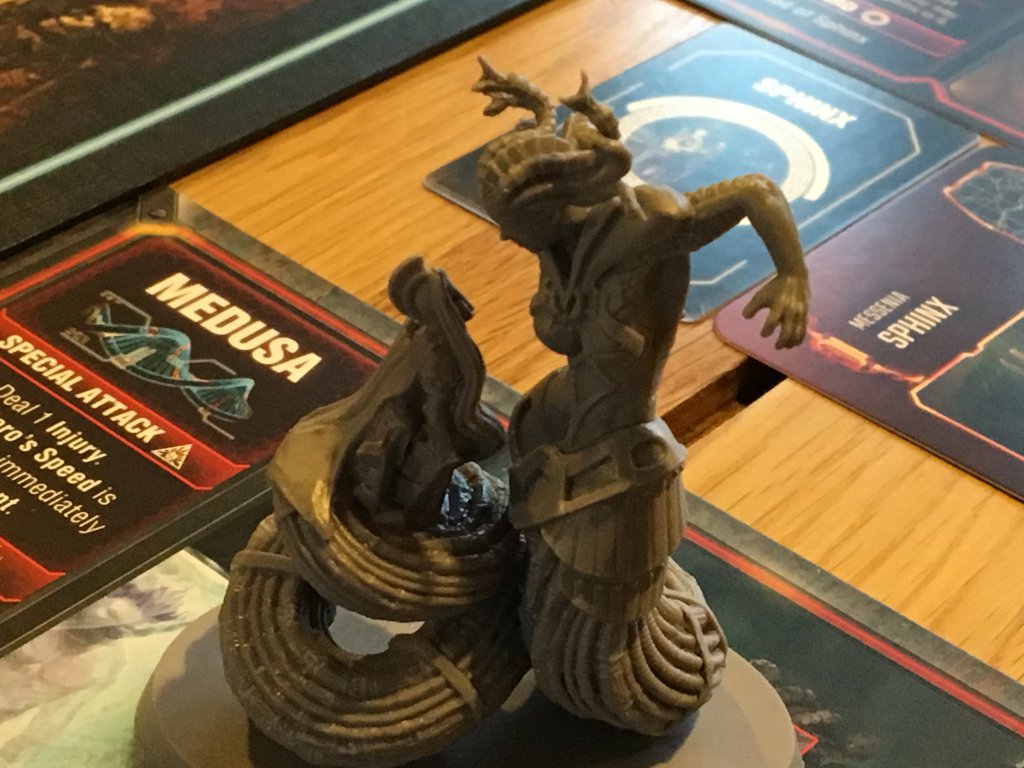

Considering it has a fairly high RRP, you may expect that Lords of Hellas is a box full of beautiful things; and it is. What you might not be prepared for is just how much stuff it contains, or how simply and effectively all that stuff comes together to make an excellent game. Set within a single plastic organiser, you’ll find seven monsters, four heroes and three huge god statues split into four pieces each. You’ll also find one of the most attractive boards I’ve ever seen, as well as around a hundred hoplite and priest figurines in eight different sculpts and four different colours; Not to mention several decks of cards, two booklets and a few other odds and ends.

Now this might sound like a lot – and from a value for money perspective, it is – but once set up the game has a very logical flow that just works. There are four different ways to win (which I’ll explain later) and one of them relates to the three dismantled statues. Each of these begins as nothing but a base, which is then built up over the course of a game. At around six or seven inches high, these statues create a lot of physical drama, especially since completing one immediately triggers an endgame scenario.

Elsewhere, each of the monsters is just as dramatic, and almost as big. Brought to the board through randomized event cards, each monster is a terrifying presence that can disrupt even the best laid plans. Slaying these beasts is also a win condition, however, so whilst your rank and file might want to stay away from them, heroes can actively seek them down to do single combat. I hope I’m already conjuring up scenes of a powerful, three dimensional experience, but if I’m not, add to the vision great handfuls of well sculpted rank and file troops sitting on the detailed, painterly board and you’ll get the picture.

Player aids, monster cards, customizable hero boards and other paraphernalia round out the supporting cast, whilst decks of cards for events, blessings, artifacts, combat and more drive the action and inform decision making. Somehow, what looks like a ton of components on a very busy board actually supports the fluid and flexible gameplay that I’ll explain in a minute. The manual isn’t incredibly well laid out, but I will say this; it got me up and running in about eight pages of key rules and just thirty minutes of trialing actions, which is quite a feat.

Turn Structure

I’ve mentioned the fluidity of Lords of Hellas’ gameplay already, but ironically, that flexibility which I love about it might just make it hard to structure an explanation of what happens in game. That’s mainly because, whilst Lords of Hellas has a structure that passes turns from one player to the next much like any other game, what players actually do on their turn is highly variable. Usually, the choice of what to do will depend on which of the win conditions the player wants to target, as well as the current board state.

On their turn, a player can take any and all of the normal actions, which include moving their hero, moving hoplites (based on the hero leadership value), praying and using artifacts. Once done with these actions, the player will then choose one (and only one) special action, which must then be covered with a token. On subsequent turns, the coveted actions will be unavailable until one of the players chooses the Build Monument action, which is effectively the trigger to refresh all actions and then activate the Monster and Event phases of the game.

The special actions are generally more powerful, which is exactly why they have a limited use. Players can prepare, which allows them to draw combat cards or recruit up to two hoplites wherever their hero is, they can recruit in all their cities (which generates far more hoplites), they can build temples (which may trigger a blessing draft) and they can march troops. There are also some less commonly used actions, like Hunt (for hunting monsters) and Usurp, which allows a player to take automatic control of a region that shares a colour with a glory token that they already hold. Finally, there is the Build Monument action, which effectively triggers the end of this round as I explained earlier.

When this happens, all players remove all priests from the board and return them to their pool, then generate an additional priest for each temple they hold. All action tokens are then removed from the player boards, which means that all special actions are once again available. The player who took the Build Monument action then adds one additional layer to the monument of their choice, effectively increasing the benefit that the monument offers to players when they take the Prayer action. Next, that same player rolls the Monster Die and takes action accordingly – sometimes moving monsters towards their enemy, or otherwise dealing damage in the region where they currently stand. Finally, an event card is drawn and resolved.

During the setting up of the game, the players will have drawn seven event cards to support the initial construction of the game. Event cards include monster and quest cards, each of which will show the location where the monster or quest will spawn. During setup, monsters will appear on the board in their basic form only, but once the game begins and event cards are drawn during play, duplicate monster cards will cause the monster in question to mutate, which makes it even more dangerous. On the subject of fighting monsters and tackling quests, there’s a whole mini game focused on each that I won’t go into detail on, but needless to say, both are as quick and entertaining as the rest of the game, adding flavour rather than complexity.

Game Experience

Lords of Hellas is a big game to set up, but it’s so very logical that it’s hard to find fault in it, despite its massive footprint. I mention this because I’ve been critical of other sprawling games that use lots of individual card decks (Fallout, for example) because of the fiddliness, but Hellas is simply straightforward. Adherence to common sense can’t be overstated in my opinion and it’s refreshing that almost every deck of cards goes where you think it should, as do all of the other pieces – there’s a thoughtfulness to the way that the rules and the components intertwine which I really rate.

Once the game is underway, the same is true. Each player begins with two hoplites and one hero, each of whom comes with an ability and a starting bonus. Whilst the list of actions might seem daunting, relatively few of them will be available to players at the beginning of the game, so the decision on starting location (which is always a free choice of any unoccupied space on the map) is important. Placing your troops onto a region with two or less population strength will mean that you can claim it immediately, opening up an instant recruitment or build temple action. Other players might spot a quest that they can start with their opening attributes (quite rare) so they’ll go for that.

From there on out, the number of possibilities grows organically. Once you build a temple you’ll have a priest, they can pray and strengthen your hero, then your hero can undertake more powerful quests. If you conquer city regions, you can recruit faster, get enough hoplites and you can take power regions with Sparta (double recruitment bonus) or the Oracle of Delphi, not to mention being able to take control of a monument region and claim the artifact of the appropriate god. If your hero is strong enough, you can tackle a monster, or if you have a numerical advantage, you might as well invade your neighbour — the possibilities are endless, but never daunting in the way that games of a similar scale can often be.

Ultimately, you’ll be after one of the four victory conditions; either build and control a monument, then hold it for three turns, control two lands (which is a group of like coloured regions), slay three monsters or control five lands with temples in them at the end of a round. I personally find monster slaying to be the hardest, but there are hero abilities and artifacts that make it easier, and it’s entirely possible to build a hero just for that job. Similarly, achieving the temple victory can be done to a certain extent by stealth, as can controlling two lands. Targeting the monument victory and triggering a three turn countdown is essentially the most impressive, but it paints a big target on your back!

Having so many ways to win makes Lords of Hellas a very interesting and exciting experience each time you play, which is something that I really love about it. It isn’t infinitely variable in the sense that there is always something new to see in a draw deck, or a variable board layout, but it offers a real opportunity for players to test and hone different strategies over many games and it is compelling enough to make them want to do so.

Conclusion

As I said right at the beginning of this review, I think Lords of Hellas may be my favourite area control game and perhaps, it will be one of my favourite games this year. It certainly is at the moment, thanks to a perfect blend of sensible rules and structure, exceptional miniatures, a wonderful range of victory conditions and a lot of variety. It plays fantastically well at either one or four players and is still a lot of fun at two or three, with perhaps two being its weakest configuration. It offers genuine strategic depth as well as a ton of flexibility and it plays in just about an hour and a bit — maybe ninety minutes — so it never outstays its welcome.

If you like area control games or dudes on a map, then you need to add Lords of Hellas to your collection. If you’re unsure on the genre, then start here. From the basic way that hoplites spread across the board to the way that heroes tackle monsters and quests, Lords of Hellas is as thematically exciting as it is mechanically interesting. There is drafting, card based combat, risk and reward and so much more — but almost nothing in this game comes down to luck. It’s a superb game and a fantastic design, which I am certain I will be playing for months to come.

A copy of Lords of Hellas was provided for review purposes, and can be purchased from all good local games stores. For online purchases, please visit 365 Games

Comments are closed.