When I first began Fugue in Void, I thought it was broken. Starting on a black screen (‘This is the story of a mind’, some text read), a small, glowing form shuttered for a few minutes. Some low synth drones rumbled, but nothing appeared to be changing.

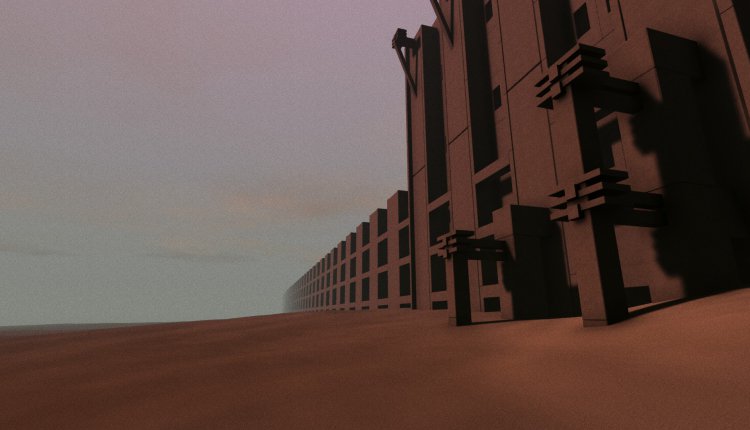

Of course, it wasn’t broken. There’s just no interaction at the beginning, no expository cinematic, no tutorial. Just a patient tour of disparate landscapes and shivering polygons. And once you settle in and acclimatise to what you’re getting into, it’s all rather breathtaking. Pass by ovals, tubes, rectangles and riverbeds; abandoned cityscapes, lifeless deserts, all dressed up in gleaming grayscale. Moshe Linke’s newest game starts pensive, patient, and builds — in proper fugue fashion — into a surprising knot of thoughts and moods.

Fugue in Void is, at its heart, a walking simulator. It has a few light puzzles strewn about, but nothing that will ever stop you in your tracks. Mostly, it wants to move you through its interiors — it forces you to step on a series of switches strewn about each level as a way to ensure you’ve seen enough before moving on. This isn’t nearly as rote as I’m sure it sounds. If you’ve made it past the non-interactive intro, you’ve accepted the game on its own terms — accepted (hopefully) that there’s worth in touring the halls to see for yourself what’s to be found.

There’s a lot hiding in its halls. If you’ve played a Moshe Linke game before, all the expected gosh-wow-ing at brutalist spires, arches and concrete chambers will tumble your heart. Linke really is a master at building sleek, towering spaces: magisterially empty worlds that leave you feeling small. Fugue in Void is a reflective affair, and a quiet one, in turns lonely and unsettling.

But Fugue is a clear step forward from Linke’s previous games. First among its steps is the sheer breadth of the thing: a full forty-five minute whirlwind of alien worlds. It’s nothing earth-shattering, just a logical evolution of the brewing walking-sim scene. But a playtime too large for a morning coffee makes it feel surprisingly meatier than others within its genre.

Its deliberation, too, sets it apart. By that I don’t mean a story, per se, but rather a clear, intentional pacing. It almost feels like an ambient Brendon Chung game, the way scenes splice together, build and compliment one another. The sum of their parts isn’t something that can be very valuably conveyed in words, so I won’t bother approximating it, but it does come together to form something total. It has an ending I won’t spoil that wordlessly, strangely ties it all into a bow I found to be surprisingly understated given the grandiose scale the rest of the game pumps out.

That is a good encapsulation of Fugue in Void. For all its vast interiors, gnarled sculptures and exaggerated lighting, it never loses a strange intimacy. Everywhere you go, you go alone. Nothing feels like home — or anything else you might call your own — but there’s no one around to scrutinize your meandering or interrupt you as your eyes turn to where the light gathers. It’s just you and a marvelous open-close of space — worlds within worlds humming fugues for nobody.

You can get Fugue in Void on Itch or Steam. And, if you like it, consider throwing some dollars at the developer’s Patreon.