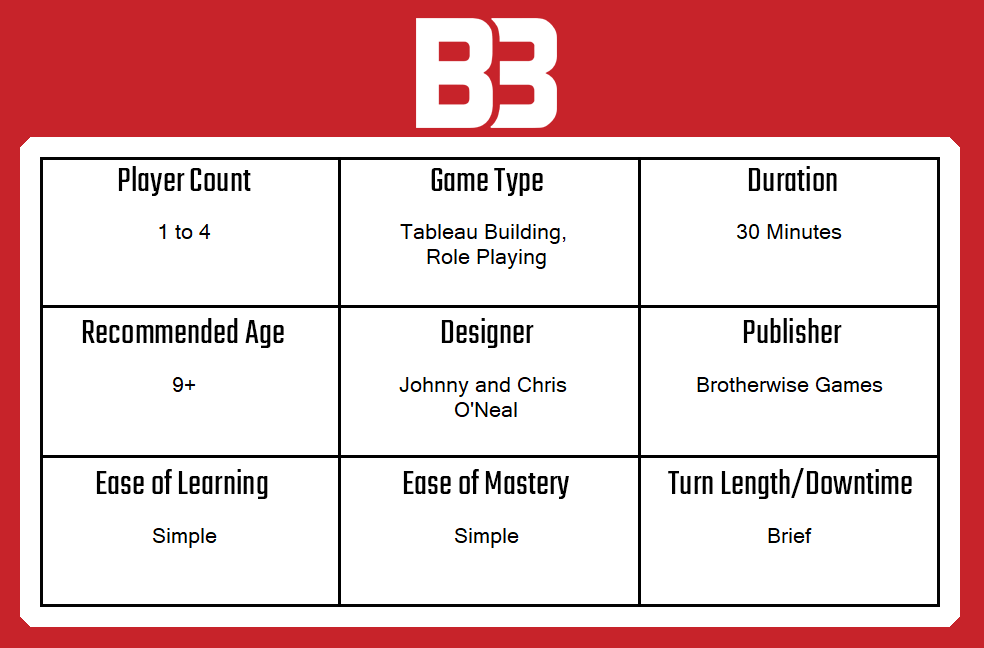

Brotherwise Games’ Call to Adventure is a card based narrative adventure game that combines a unique “rune throwing” mechanic with classic tableau building.

Playing between one and four players, Call to Adventure initially surprised me with its simplicity and speed of play. With a hard limit of more or less nine turns per player, this is a game that covers a lot of ground in a short space of time. Whilst I found that Call to Adventure was slightly lacking in long term decisions and depth, it more than made up for that with a clever story building system and an infectious way of causing players to want just one more game.

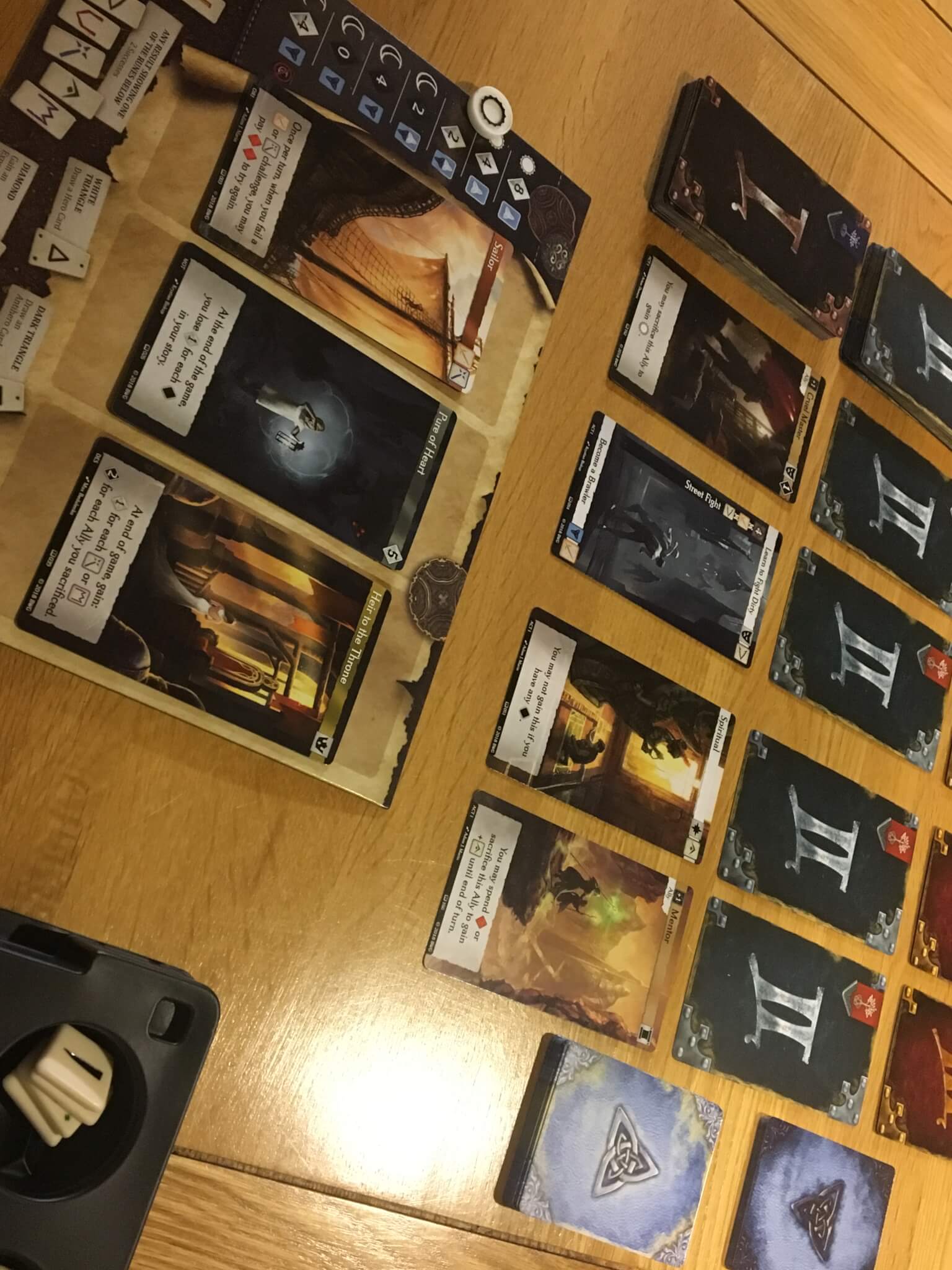

The setup of Call to Adventure is overwhelmingly simple. Each player draws two Origin, Motivation and Destiny cards, then chooses one of each to keep. In competitive mode, their Destiny card is kept secret because it will result in end game points, whilst the other cards are open information. In cooperative or solo mode (which is what I used to produce the photos in this review) all cards can be left face up.

As you’ll see from the pictures, this mix of cards can result in some very interesting narrative combinations. You might be a humble farmer who was pressed into service as a squire, with a destiny to become a King or perhaps even the Chosen Hero. Call to Adventure features enough of these different choices that they almost always feel different, but somehow, I haven’t found a single combination yet that didn’t work to create an evocative, personal feeling narrative.

With the setup done and these cards on your player board, you’ll also take three experience tokens and setup several stacks of runes in the middle of the table. Three decks of cards marked with Act I, II and III on them will be set up from bottom to top, then four cards are drawn from each and placed face down. The Act I cards are then turned face up and the game can begin. In solo or competitive mode, there’s a little work to do setting up an adversary and their deck, but it’s all simple stuff

On their turn, a player has several choices to make. All of them are quick and simple. As their action for the turn, a player can either take a trait card, which is always a case of simply picking up the card and then sliding it under the Origin, Motivation or Destiny card associated with the current Act (I, II, and III respectively.) Alternatively, they can undertake a challenge.

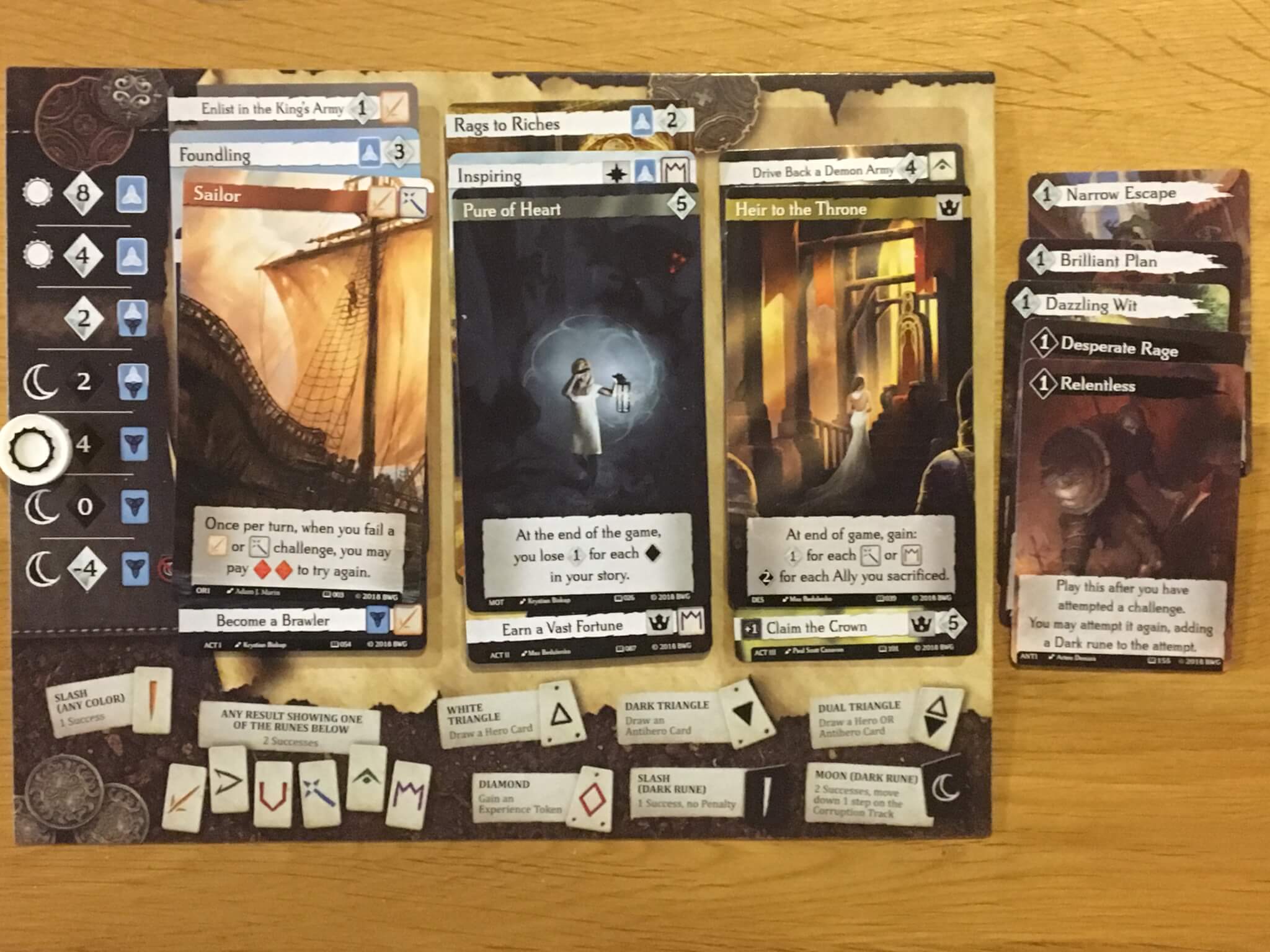

Challenges end up working in the same way (in that they are also placed under the current player card) but first, they require a test. Each Challenge has two paths, one of which will usually be slightly harder.The various paths will offer benefits such as experience, new trait runes or end game points. Tests require a certain number of requests to be rolled on a set of runes, which act as dice do in any other game, but their uniqueness adds an element of je ne sais quoi to Call to Adventure.

Whilst we’re talking runes, traits and tests, let me explain a bit more. Whenever a test occurs, the player taking the test will always roll three base runes. Two of these runes have a success marking and a miss marking on them, whilst the third has a success marking and a prompt to draw a card from either the hero or anti-hero deck. One or more experience tokens can be spent to add dark runes, which add one or two successes (but can move a player closer to evil) and depending on the test, other runes may be added.

When I say other runes, I specifically mean other runes as shown on the challenge and only if you the player has access to those runes from the cards that have already been added to their tableau. A player who already has a combat rune symbol among their traits or beaten challenges will be able to cast that rune in order to overcome a challenge that allows fight runes — for example one where you must defeat an enemy.

In Act II and III, many challenges require maybe five, six, seven or even more successes to be thrown, so taking on challenges that you don’t have supporting runes for can be very challenging or even impossible. Some cards from the hero and anti-hero decks can help, with some granting automatic successes or adding additional runes. Certain Ally cards (which are placed below an active challenge when drawn) can be earned and will allow similar effects.

This loop of adding traits, allies and challenge cards to the personal vignette of your character occurs three times in each Act, with a new card being drawn to replace traits taken and challenges defeated. Players can also spend an experience to ditch a current card and draw a new one, which is useful if you feel that your character lacks access to the cards and will benefit them in achieving their destiny.

Once three cards are taken from an Act, the player will reveal the cards from the next Act, turning them face up, and repeat the process. Depending on the game mode, the final turn of the game might involve tackling the Adversary, but assuming that you’re playing competitively, after the ninth card is taken and the round ends is when endgame scoring will occur.

There are several factors to consider when scoring in Call to Adventure, which will largely begin with how closely aligned your character is to their destiny. Characters will gain or lose points based on their position on the hero/anti-hero track, whilst some cards come with their own triumph and tragedy that works in a similar way, depending on the kind of character you’ve created. Played hero and anti-hero cards are each worth a point, as are unused experience points — there are a few other cards that can also earn points. Ultimately, the player with the highest score is the winner.

Now, there’s a lot to like about Call to Adventure, but let me tell you what I don’t like, since those bits are relatively few. When I choose to play a board game, I’ll generally choose a longer, more in depth game — like a medium weight euro. As I’ll go on to say, I do enjoy the experience of creating a character and seeing their destiny fulfilled, but the downside of how that manifests in Call to Adventure is quite fleeting.

At around thirty to forty five minutes per game, I’ve felt on a number of occasions the game drew to a conclusion just as players were getting to know their character — for a game that does such a good job of creating emergent narrative, this feels like a shame. I have also played a number of games (always when either solo or at low player counts) when the four cards on offer in the current Act were simply not of interest, but I didn’t have any experience to buy the take the Journey action (which allows the player to swap one card for a new one) with.

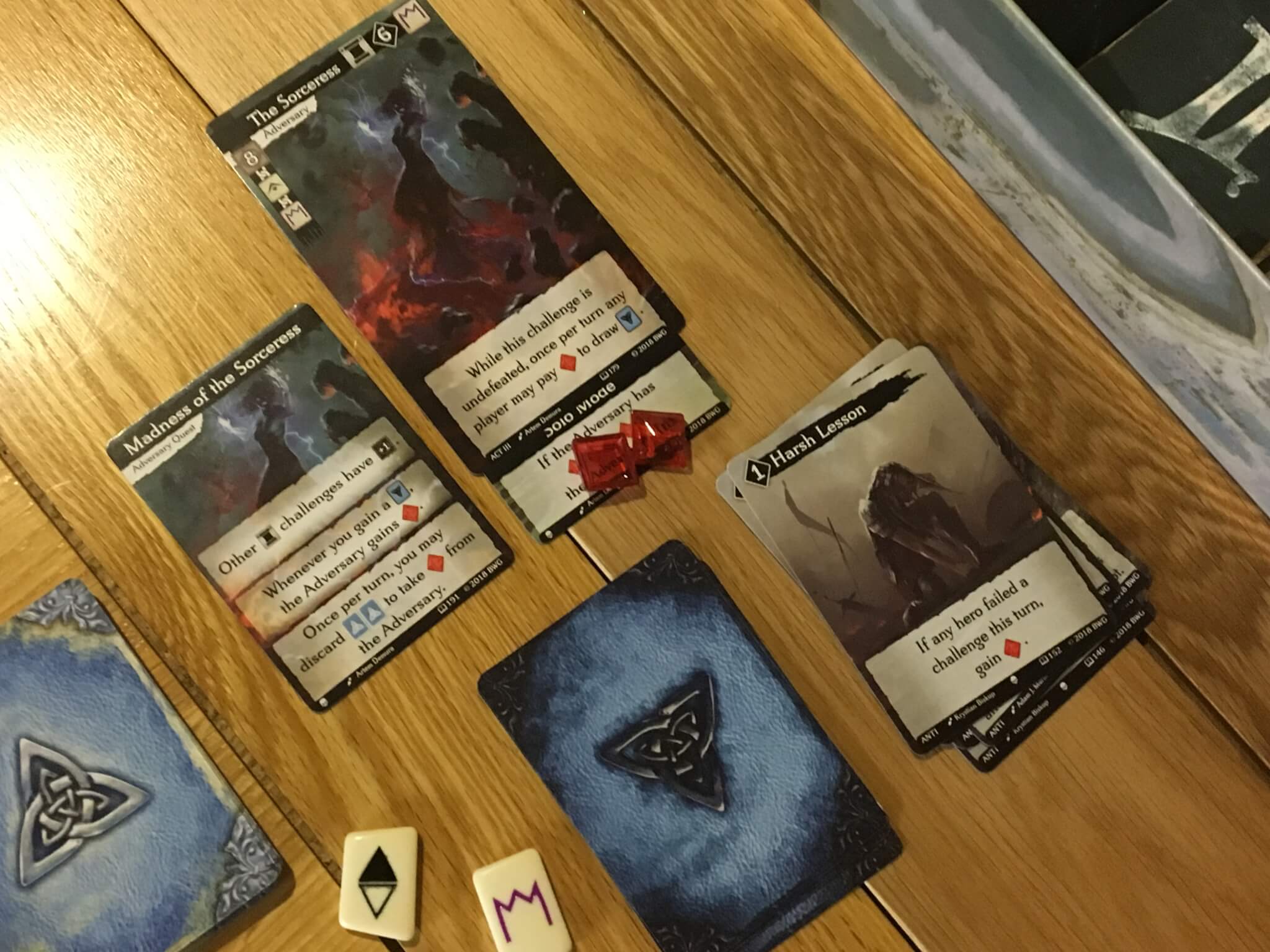

My final, minor criticism is that in competitive or solo modes, I didn’t really feel any sense of threat from the Adversary. Each of these powerful enemies has their own set of rules that affect the basic gameplay, as well as a win condition relating to how much experience that the Adversary can gather based on player count.

The Adversary also has their own deck or cards that can disrupt the player(s) but in general, the chances of winning and losing often depend only on chance — as dictated by the runes. Regardless, I still enjoyed these experiences, especially solo, which can be played in as little as fifteen minutes beginning to end.

Now, onto the positives, of which there are several. I mean, firstly, the speed of play is also a really good feature. Having a game that can engage players as much as Call to Adventure does that might be over and done with in half an hour is quite rare. There’s no doubt that playing this game is rewarding and like I said earlier, the combinations of different Origins, Motivations, Destinies and Traits come together in a very thematic way.

When I play Call to Adventure, I get a feeling of Roll Player about it in the sense that the players are really creating their own characters and building a mythos around them. Where Roll Player concentrates on the statistical elements and technical prowess of the characters, these features are secondary (via the runes) in Call to Adventure, whilst the story takes centre stage.

Over and above the speed, I also enjoy the simplicity of play in Call to Adventure, which makes it very easy to teach. Between speed of play and ease of learning and teaching, Call to Adventure presents a fairly unique gateway game option. I definitely wouldn’t say that it offers a route into any specific kind of heavier game, but it’s a unique and fun proposition in its own right.

I don’t think any of this would work if Call to Adventure wasn’t so beautifully presented. Primarily, this is a comment about card art, which is delivered to an exceptionally high standard throughout, with a consistent painterly style that strongly hints at the race, sex and look of the characters, but doesn’t show them in fine detail — allowing the players to fill in the blanks. The custom runes are very cool and the manual is well presented and suitably brief.

Overall, Call to Adventure is a very enjoyable (albeit light) experience that is fast and straightforward enough to be enjoyed by any novice or casual gamer. The weight and speed might put off more committed gamers to an extent, but speaking as someone who likes heavier games, I’d also say that there’s a roll for Call to Adventure to play as part of an all night gaming session as a warm up, in between filler or after the main event style game.

Call to Adventure is available now. You can find out more about it the website of publisher, Brotherwise Games.

Love board games? Check out our list of the top board games we’ve reviewed.