Azul: Summer Pavillion is the ultimate expression of Michael Kieslings’ grand design

With so much praise lavished on the first two games and such a simple game concept to work with, I couldn’t imagine how Azul: Summer Pavilion could possibly have improved on the first two games, yet somehow, it has.

After all, just a couple of years ago, we listed the original Azul as our favourite light to medium weight game of the year. The second game in the series, Azul: Stained Glass of Sintra also drew our praise, with reviewer Sara Yee describing the game as “perfect looking” in her review. We are not the only ones to praise the Azul series, of course, and Michael Kiesling’s simple tile drafting and placement games have fast become some of the most lauded board games in recent history.

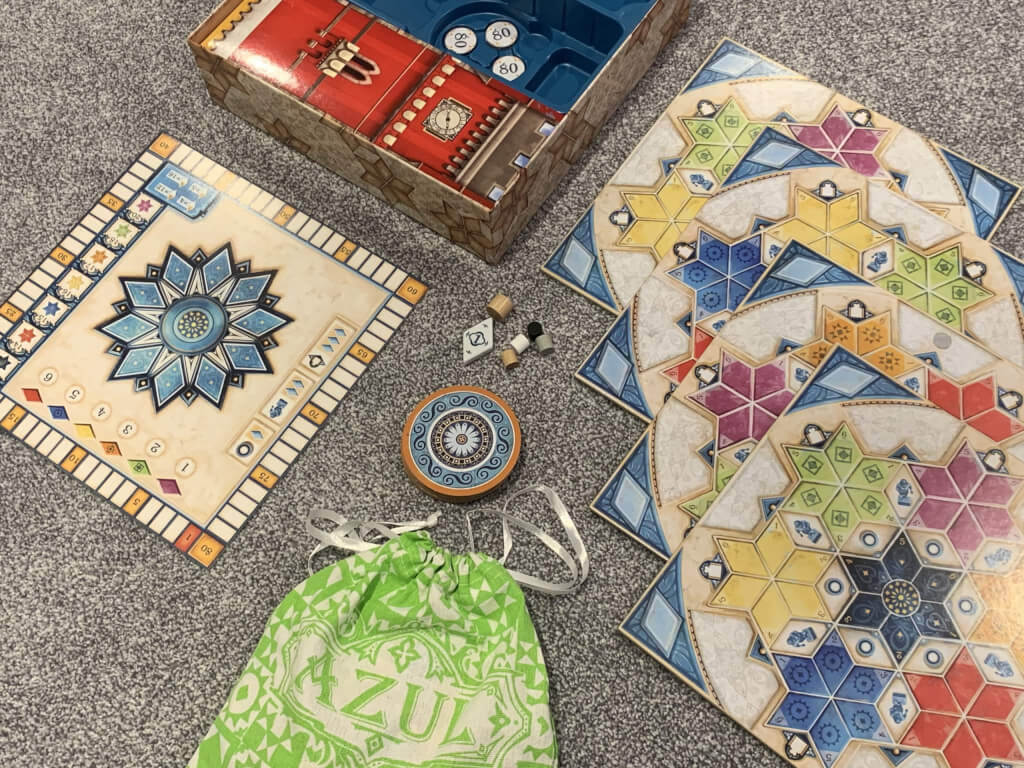

Like the two previous games, Azul: Summer Pavilion sticks close to the basic idea that players will choose tiles from several factory locations, to then place them on their own personal display. Thematically, the actions are said to represent the players vying to build King Manuel I of Portugal’s summer house, but in reality that fluff is unnecessary because Azul: Summer Pavilion is pure abstract strategy at its very finest.

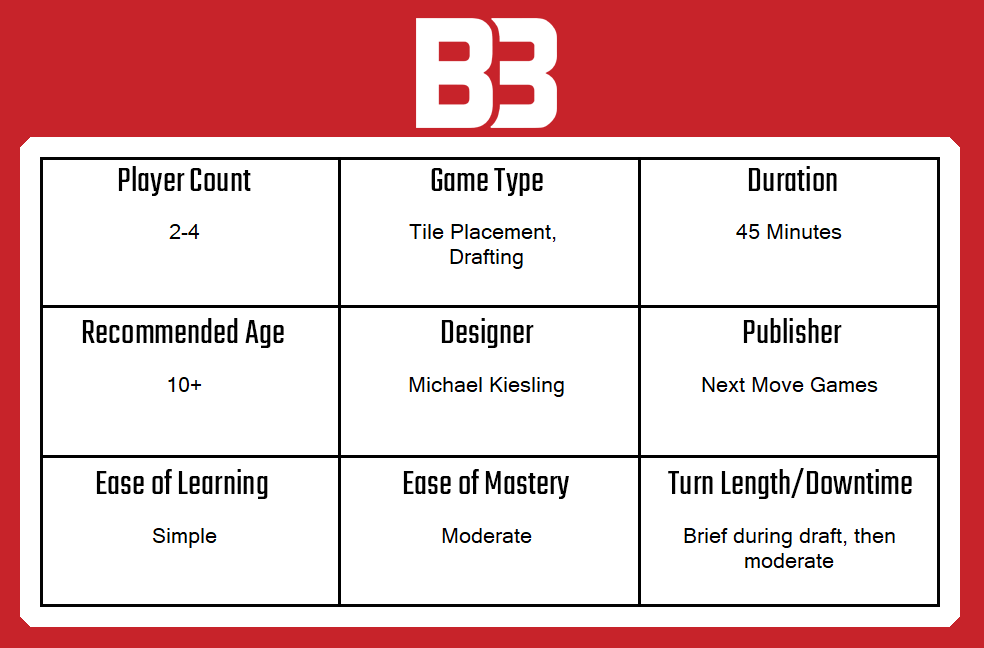

At a mechanical level, Azul: Summer Pavilion is very similar to the previous games, and each round begins with the players drafting diamond-shaped tiles in the six different colours. I should note that for colourblind players, the yellow and green tiles are extremely close to each other in colour, but the inclusion of a symbol on the green tiles helps to differentiate the two.

The draft itself simply involves the active player choosing one of the tile factory tiles and then claiming all tiles of one colour from it, which they will then take into their supply. All tiles from other colours (each factory holds four tiles max) will be shoved into the middle of the table. This process repeats until someone decides to take tiles from the centre whilst following the same rules – at which point they must also take the “first player” tile and lose a point.

The only notable difference in the drafting phase between Azul: Summer Pavilion and the previous two games, is the inclusion of wild cards. Each of the six game rounds will have a different wild card colour, and when drafting tiles, players may only ever take one wild card tile, no matter how many are in a location that is being drafted from. I’ll explain the purpose of these wild cards later, but just know for now that there are times when taking one wild tile is better than two or more regular tiles, and working out when is one of the subtle complexities of the game.

Once all of the tiles have been drafted from both the factories and the centre of the board, the game will move onto the next phase, which is all about placing the tiles. Beginning with the first player, each participant will place a tile onto their own board, scoring one point for each tile placed, plus a bonus point for each tile that the placed tile is adjacent to. So for example, a single tile will score one point, whilst a tile placed next to three existing tiles will score four.

The actual placement of tiles is where Azul: Summer Pavilion really differentiates itself from the other games, in several ways. Firstly, each player board is made up of seven six-pointed star shapes, one for each of the tile colours, plus a seventh star that sits in the middle. Each point of every star has a number on it from one to six, and to place a tile on that point, the player must trade-in that many tiles of the colour that matches the star.

To use another example here, if we were placing yellow tiles and wanted to place on the point marked with a one, we’d simply take a single tile and place it down on the point marked with a one. If we wanted to place on the yellow point marked with a six, however, we would need to have six yellow tiles, five of which we would discard into a cardboard tower, and the sixth of which we’d place onto the board.

Tiles spent and placed must all match the colour of the star they are being played onto, with two exceptions. Firstly, the central star has no colour and a tile of any colour can be placed onto any of its points, as long as the correct number of tiles is paid and no other point is already occupied by tiles of that colour. The second example are the wild tiles, which can be used to substitute a tile of any colour — as long as there is at least one tile of the “proper” colour matching the star onto which the tile is being placed.

Whilst this is a little elaborate to explain, and certainly feels more complex to learn than either previous game, placement in Azul: Summer Pavilion soon becomes second nature. At the end of the placement round, any tiles that a player can’t place can be held (up to four) or must be discarded. Any tiles discarded will cost the player a point per tile, but saving tiles from one round to the next can be a very valid strategy, especially if the player chooses to retain tiles that will become wild next round.

But wait, there’s more! Between each of the points at which the stars touch on a player board are statues or other sculptures. As the player surrounds those sculptures, they will gain the ability to draw one, two or three tiles from a separate board that houses a ring of randomly drawn tiles. What this means is that during the placement phase, there are opportunities for players to pick specific tiles that can be used during the same placement phase to bolster their efforts.

Now all of this tile placement would be fairly arbitrary if there wasn’t a bonus for completing the stars, and indeed there is an end game scoring phase that awards points to players who have completed all the points of a star, as well as players who have completed the points of each star that are marked with three, four, five or six. Endgame scoring can dramatically change the standings after the final round is played, and runaway leaders are often reigned in and overtaken by players who have focused on perhaps just two or three final scoring objectives.

Between the basic drafting, the scoring, the consideration of wild tiles and how they affect each round, and the much more complex placement of tiles than in previous games (not to mention the statues and what they bring to the game) Azul: Summer Pavilion is the most strategic game in the series by miles. That said, it remains almost as mechanically simple as the other games, which means returning players will feel immediately at home whilst newcomers will pick the idea up quickly.

Thanks to this more complex and deeply strategic gameplay, I am of the opinion that Azul: Summer Pavilion is the pinnacle of the trilogy to date, and I honestly don’t know where designer Michael Kiesling could take Azul next, if anywhere. For me, this is the perfect Azul game, but if you are a complete novice looking to take your first steps into modern board gaming, I’d still recommend the original Azul thanks to its simple, accessible gameplay. The completionist in me intends to keep all three games anyway, even if the first and second (in particular) feel a little redundant.

You can purchase Azul: Summer Pavilion on Amazon.

Comments are closed.