Shipwrights of the North Sea is the final entry in Garphill Games’ North Sea Trilogy, which also includes Explorers of the North Sea and Raiders of the North Sea. Although each game is linked by beautiful artwork and the viking theme that runs across them, each is a standalone game which is simply set in the same universe.

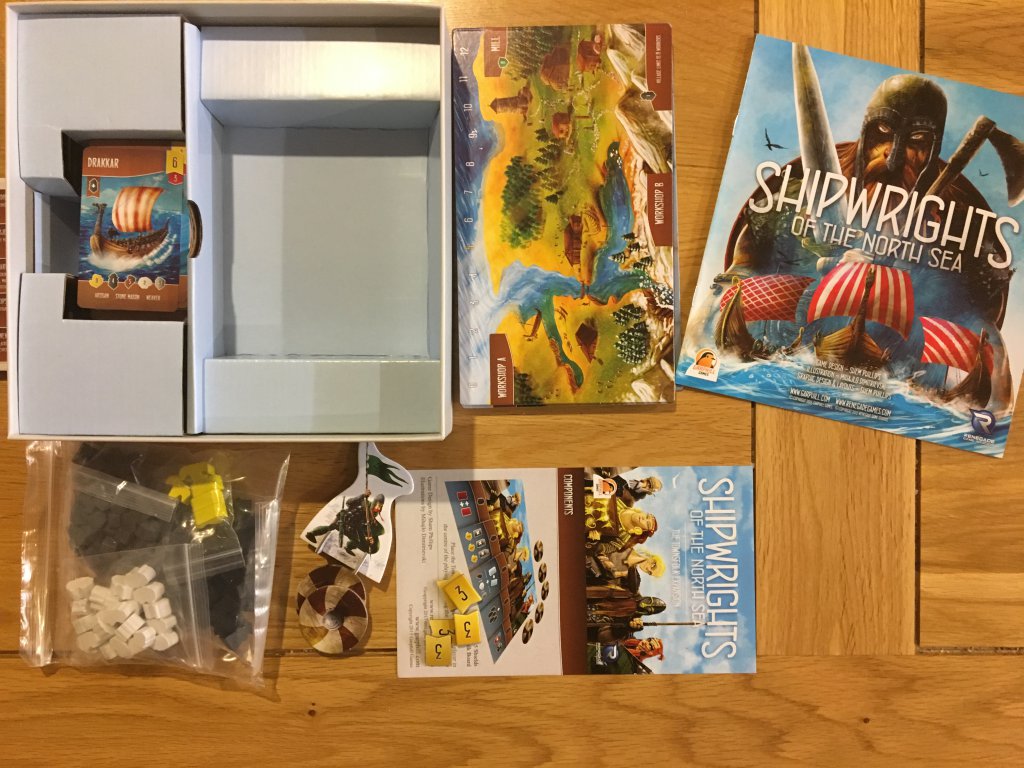

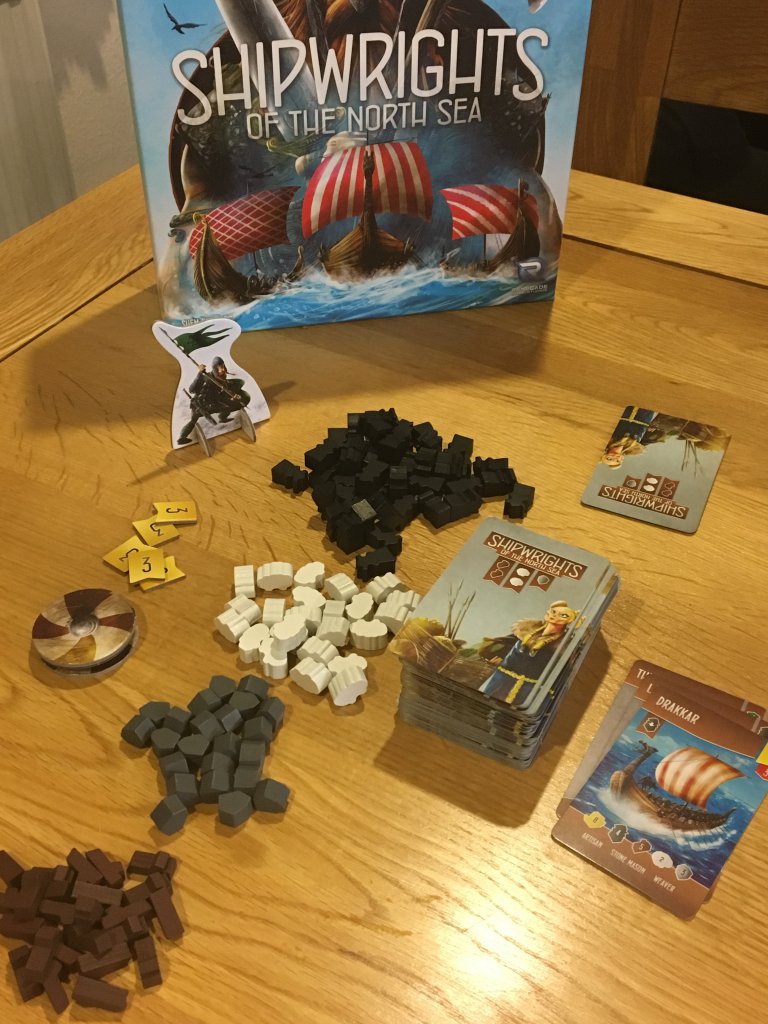

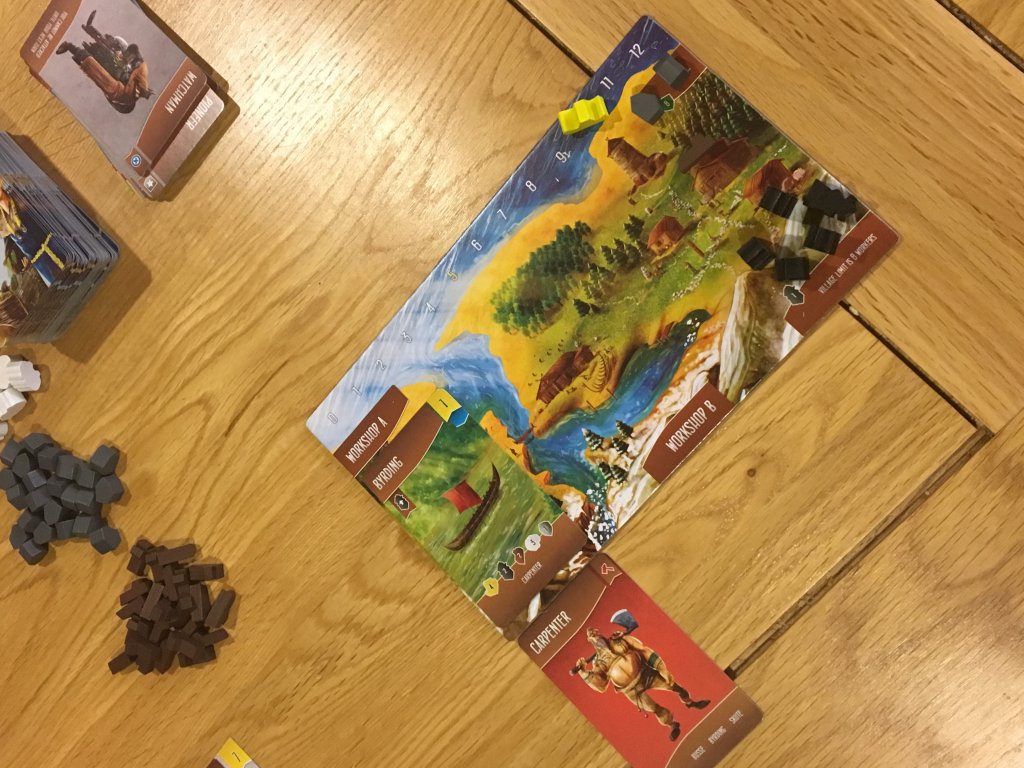

Shipwrights of the North Sea is a card-drafting, resource-management and engine-building game that is both relatively simple and fairly compact — although due to the number of small pieces and the large deck of cards involved, it isn’t what I would describe as a travel game. Two to five players each take control of a viking village, which they must then manage to construct up to four viking ships of varying victory point value. Each ship costs a different number of resources (gold, wool, iron, wood) and one or more specialist villagers to build, so maximizing efficiency is key.

To expand their villages, players must draft from the deck of 128 cards that feature prominently in Shipwrights. Each round, the player holding the Pioneer standee is the first player, which affords them the powerful benefit of leading the draft during a phase called The Morning. The drafting player draws cards equal to the current number of players plus one, assesses them, places one face down, then passes the remainder to the next player. Each player after the first takes a card until only one remains, at which point it is secretly discarded. This process is repeated twice more (beginning with the same first player) until all players have three cards.

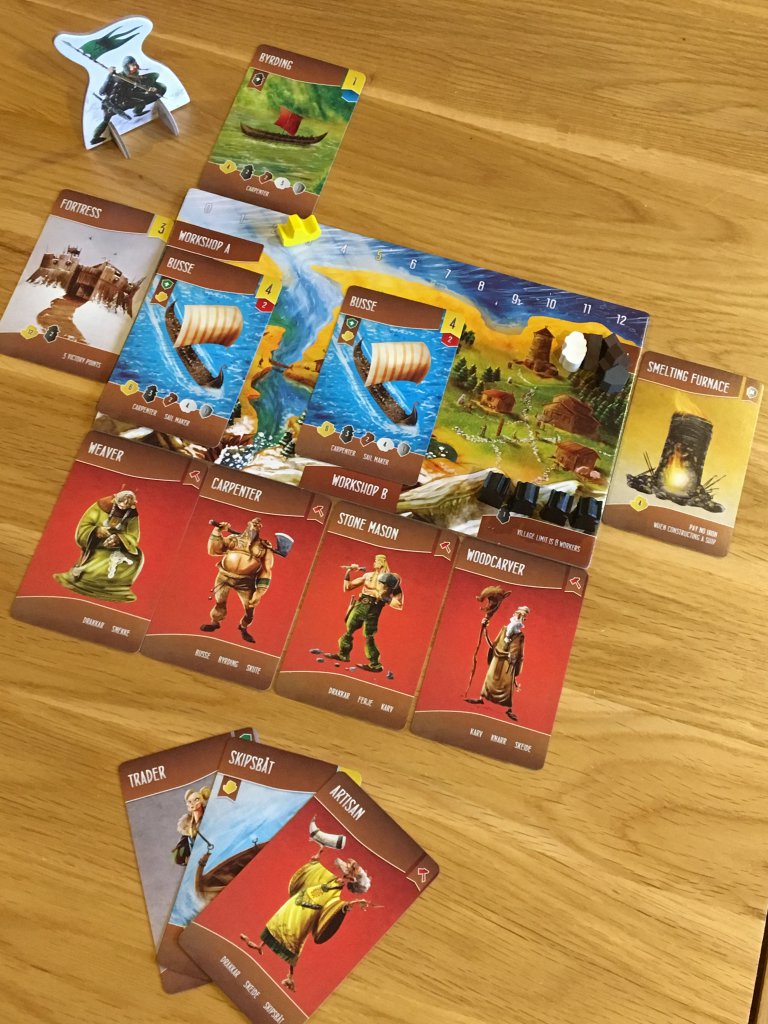

During the next phase (which is called The Afternoon) players take it in turns to play or discard all three of the cards they drew previously. There is a fairly broad range of possible actions, with different deployment mechanisms dependent on the kind of card they reside upon. Villager cards offer instant-use effects like drawing gold or resources, as well as immediately killing a craftsman or robbing an opposing village. Up to four craftsman cards can be placed beneath each village, but once you place one, it can only be removed by specific villager cards or when it is used to complete construction of a ship.

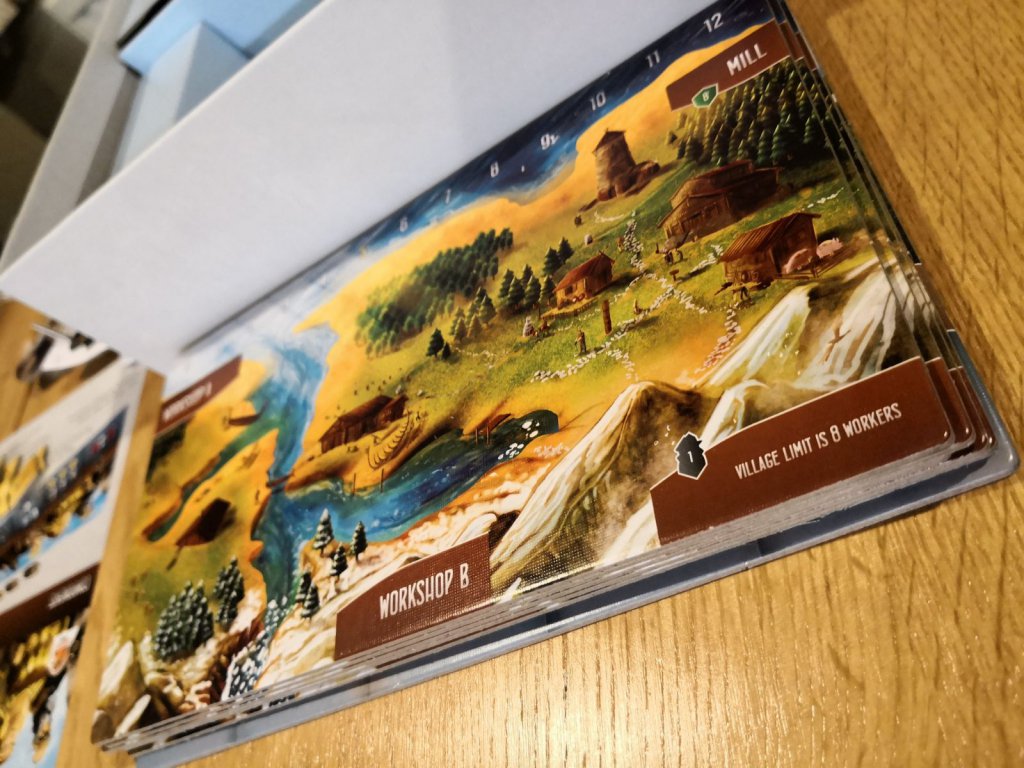

Ship cards can be placed into either of the two workshop spaces in the village (which costs nothing at this stage), whilst building and tool cards can be placed to either side of the village for a permanent bonus, but must be paid for upon placement. If, for any reason, a player can’t use one or more of their cards, then at the end of the turn they must be discarded. Several other actions available to players during The Afternoon if the right conditions are met.

These actions include trading two worker meeples and two gold for one to three resource cubes of the same type, based on the exchange rate shown on the top card of the primary draw deck. This is a really neat mechanic, although it can be frustrating to miss out on resources you need for several consecutive turns. The other main action available in The Afternoon is to complete construction of a ship in one of the workshops. To do so, players must pay gold, workers and any resources shown on the card, then discard one of each of the listed specialists — for example a Sail-maker and a Carpenter. The completed ship is then placed above the village board and can be scored at the end of the game, which occurs when any player completes their fourth ship.

Once all players have completed their Afternoon phase, a simultaneous cleanup occurs (if you guessed that it was called The Evening phase, then sadly you don’t win a prize for stating the obvious). During this phase, players draw gold and workers based on the number of relevant symbols shown on their village, then physically tidy up face-down cards, played cards and cards with a temporary use that expired during this turn. Whilst I’m not going to explain it here, the only additional complication is a bundled expansion called The Townsfolk, which introduces a few new mechanics that are managed by an additional board.

Now, if Shipwrights sounds fairly simple, that’s because it is. The components are clear and straightforward — and with relatively few mechanics to manage in the game, everything is either symbol-driven or delivered via a single, self-explanatory line of text. It’s possible to teach Shipwrights in about ten to fifteen minutes, although as I’ll soon explain, it’s quite an aggressive game with lots of player interaction that requires fairly deep thought, so I wouldn’t personally recommend it to casual players looking to get hooked on hobby gaming in general.

On that note, this player interaction is probably going to be the hinge upon which the door of your enjoyment swings. If you really like punching your friends in the face and laughing about it, then you’re going to kick the door open and let yourself in. By contrast, players who feel uncomfortable about being continuously pegged back (and having to peg back opponents) will probably want to shut that door as soon as possible.

A key mechanism of how the Shipwrights flows revolves around the need to use (or discard) most cards on the same turn you draw them. This means that each resource, ship, specialist or tool you place feels valuable. Having an opponent abduct or kill a specialist can feel really painful, as can having resources stolen when you may have waited for a long time to collect them at the correct exchange rate. The destruction of a ship you’ve been stockpiling toward is almost worthy of a table flip on some occasions. There is a villager card that protects a village for one turn and an ability in The Townsfolk expansion that does the same, but these defensive options are not strictly reliable and waste resources you usually need elsewhere.

Another oddity is the drafting mechanic, which makes being the first player incredibly powerful in shaping the draft (and therefore the whole turn). Having the first pick in any draft is always powerful, but taking first pick from each of the individual drafts feels like too much. I changed this after just a few games to a normal draft structure where each player takes first pick from their own pile and then passes left, whilst still retaining the Pioneer standee to indicate who actually played their cards first.

Whatever draft structure you use, taking it in turns to play a card would also even out some of the spikes, because in the basic interpretation of the game, the first player often lays their cards down, then has an anxious wait as each of their opponents plays his or her cards. This is usually complete with a number of ‘take that’ moments as assassins, thieves, barbarians and conspirators are played and best-laid plans torn to pieces. I’m really not exaggerating this — disruptive plays happen every single turn in Shipwrights and you either love it or hate it.

I haven’t actually played the other entries in The North Sea Trilogy, but I do admit that I am swayed by the viking theme in general. Even so, it isn’t enough to save Shipwrights of the North Sea, which for me is a bit of a miss. It’s a nice, compact game, but it has a few odd mechanics that defy normal convention — the drafting approach, for example — which make it a little unbalanced, even before you consider the bloody mindedness needed to play it.

The amount of negative interaction in Shipwrights is what really makes it hard for me to recommend however, because simply put, I don’t have a group of players it really appeals to. Constantly hampering each other to the extent Shipwrights demands is almost always going to alienate someone in a group of more than a few players. And yet even if direct conflict is what you want, there are games that do it better at the two to three player count — look at last week’s Cry Havoc review as a great example.

To summarise my feelings in a single paragraph: If Shipwrights sounds like it might appeal to you based on how I’ve described the interaction, then it probably will. It is well made and attractive and there isn’t anything fundamentally wrong with how it actually works at a mechanical level, but it just won’t be for everyone. Sadly, I have to include myself among its detractors, even though I don’t consider it to be bad, as such.

Comments are closed.