Take your loved one to play Museum this Valentines Day

With hundreds of beautifully illustrated cards and a thought-provoking theme, Museum is a recently fulfilled Kickstarter that focuses — as the name might suggest — on complex set collection.

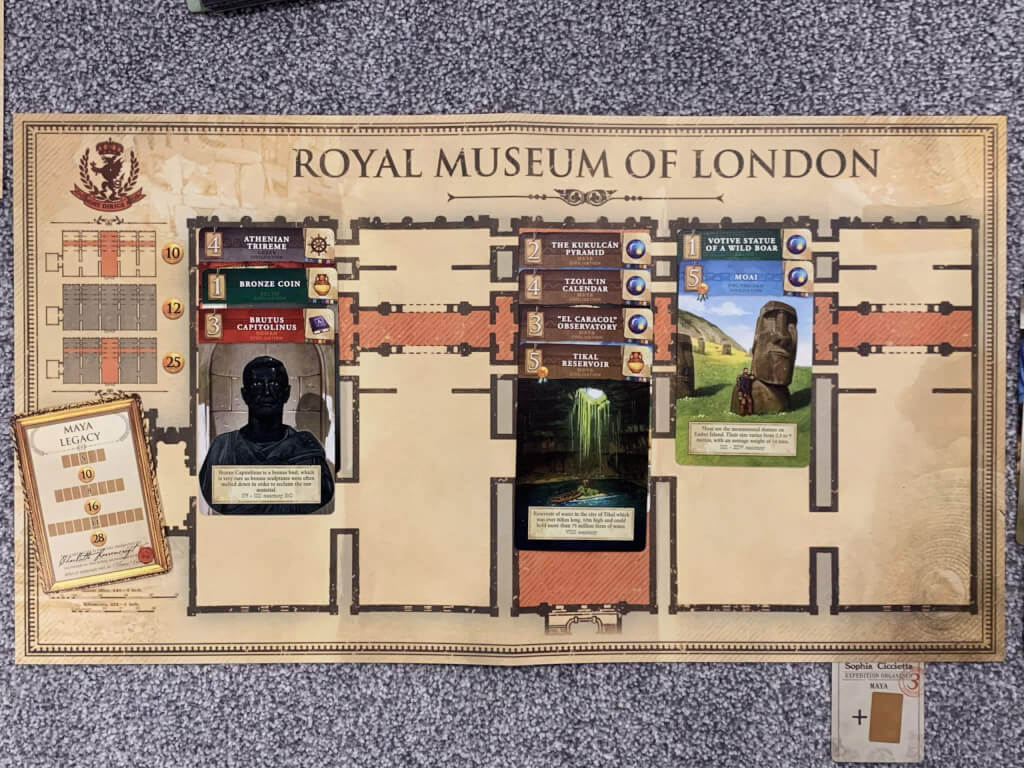

In Museum, two to four players operate as the curators of famous museums and will be attempting to lead expeditions to obtain antiquities to put on display. The ultimate objective is to have the most prestige among all of the museums when the game ends, which is achieved both during the game and as the result of several possible endgame scoring conditions.

Each player maintains their own museum board in a colour of their choice, and depending on whether you choose to play with the basic or advanced variant, the museum boards will be placed with either the basic layout or a more complex one face up. The difference between these two sides relates to how filling out the museum will score at the end of the game, and in all honesty, the advanced side isn’t much more difficult to work with after a game or two.

Setting up Museum is quite simple and clean, which is a theme that runs through the gameplay as well. There are a few decks of cards (one for each of the four sets of antiquities, plus a handful of others) to sort, but there’s no need to load the decks, cut them in bizarre ways or otherwise manipulate the cards in complex ways. The best way to set up Museum is usually to ask each player to shuffle a couple of decks and you’ll be ready to go within five minutes.

With the board set up, each player will draw one card from each of the four antiquities decks, then one from the favours deck. On the first turn, no card is drawn from the Headlines deck (which I’ll explain in a bit) and any Public Opinion cards will also be shuffled back into the deck they came from and replaced with new draws.

The game then begins with the first player, and each turn comprises of two phases. In the Exploration Phase, the active player must draw one of the antiquities cards that are face-up on the board — usually two from each deck. I say usually because some of the Headlines cards close down one of the spaces, or add or reduce the number of choices by one.

The players will each have a patron card that, alongside their museum board, offers the chance to achieve certain end game scoring bonuses based on the sets they have when the game is over. This patron card (chosen from three dealt out during setup) will usually influence the early choice about which card to draw — for example you may wish to focus on the Indian, or Maya civilisations, or you may have a more complex patron requirement that expects sets of themed artefacts — for example focused on navigation or warfare.

The interesting thing about the Exploration Phase is that the active player must draw a card and can do so for free (and why not) but each other player may then follow the active player to draw a card for themselves. Each player who does so, however, will gift the active player one prestige token which is taken from the general supply, thus giving them a bonus for the next phase, involving furbishing their museum.

This second phase is referred to as The Action Phase, and only the active player will participate. During this phase, the player will use the cards in their hand to play other cards into their museum either from their own hand, their own discard pile, or the discard piles of other players. At some point, a player will not have enough cards in hand to do this, and so their Action Phase will need to consist of an Inventory action, which simply involves picking up their discard pile and adding it back to their hand.

To provide a bit more detail about how furbishing happens, let’s pretend that we have a card worth five prestige in our hand that we want to play, as well as a three and a two value card. In this example, we would simply discard the two and three value cards for a total of five, and then we would place the five value card into our museum in any open slot. It’s worth noting that running out of museum space is very unlikely, but if it happens, it is one way in which the end game can trigger, but a much more common end game trigger is because one player reaches fifty points.

There are several other possible examples of this phase that it’s important to understand, so allow me to indulge in one or two further explanations. The first interesting nuance is that prestige points can also be spent to furbish, so in the example above, we might have spent two prestige points and the three-point card to pay for the five-point card, rather than spend both cards. This is an important decision because any prestige points held at the end of the game will simply become points that affect the final score.

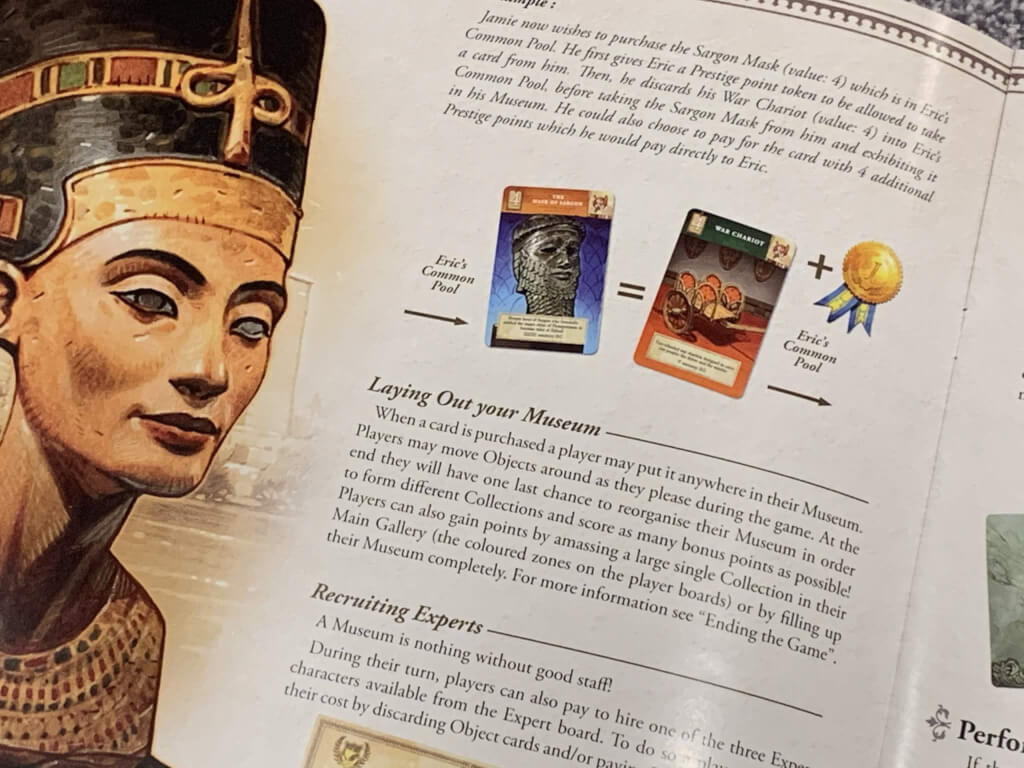

Another factor involving prestige points is the ability to furbish items into your museum from the discard piles of other players. This is simple and cannot be prevented by the other player, so any time someone decides to place a card into their discard, they do need to consider whether another player is likely to pinch it. To take a card in this way, the active player must pay the player who they are taking the card from one prestige point, and then they must spend the usual amount of either cards or prestige points to put it in their museum — but in this case, those cards or prestige points go to the player who is losing the card that will be put in the museum.

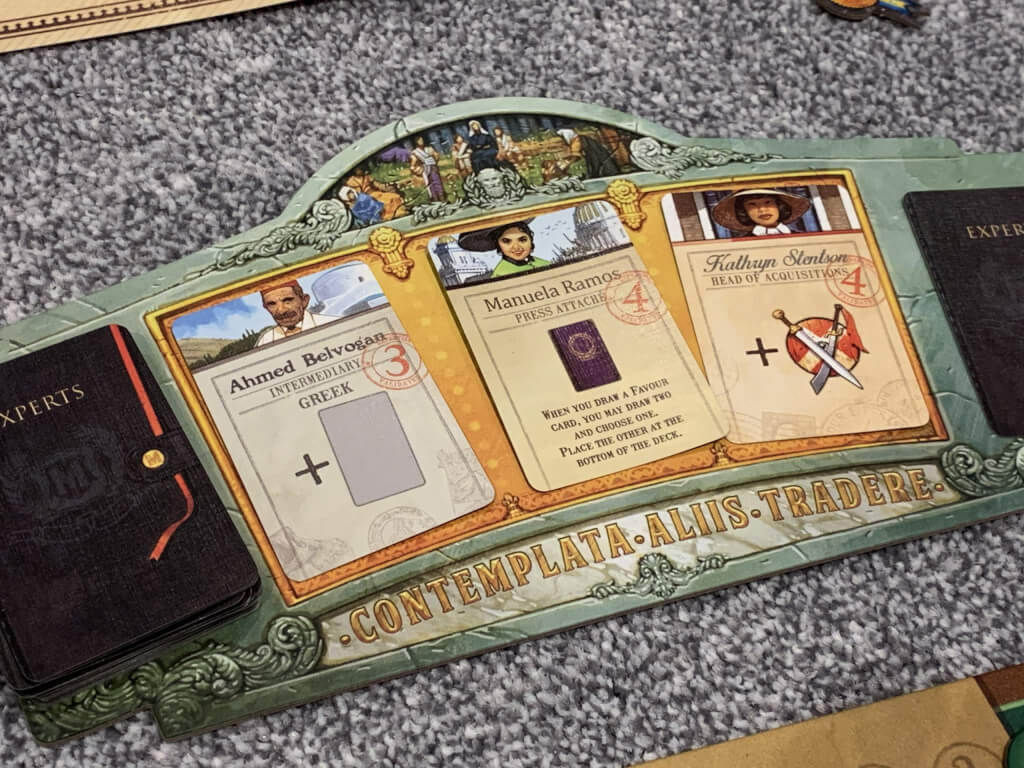

The active player can purchase and place as many items as they can afford or wish to, and may then also hire an expert if they have the prestige to spare. The expert board always has three experts shown face upon it and each one has a prestige value printed on it. Hiring an expert works in precisely the same way as furbishing the museum, and the benefit that the expert provides is effective immediately.

It’s worth noting here that hiring experts seem to happen after furnishing the museum (and that’s the way I played it) but this is one area among a few that the manual is slightly unclear on. Players may also use their favour card at any time on their turn, and there are situations where a favour card can, for example, allow the player to hire an expert for free, and this might break the sequence of furbishing and hiring. Whilst these aspects felt fiddly to me, any experienced gamer will navigate their way through these minor rules inconsistencies with relative ease and by following common sense.

Play then continues with each player taking a turn as the active player, and when a full round is complete and play returns to the original first player, a new Headline card will be drawn. Headline cards do things like close off access to antiquities from an entire region or flood the market with more of them. Some are more mundane, adding to or subtracting from the cost of furbishing.

Another thing that is likely to appear within the first round or two are public opinion cards, which are drawn from the antiquities decks when replenishing the board. Public opinion cards add tokens to the continent from which they are drawn, and at the end of the game, will score negative points for any players who hold cards from that region in their discard pile. The idea here is that the public is unhappy that museums are simply hoarding ancient goods and not displaying them, or perhaps more appropriately, returning them.

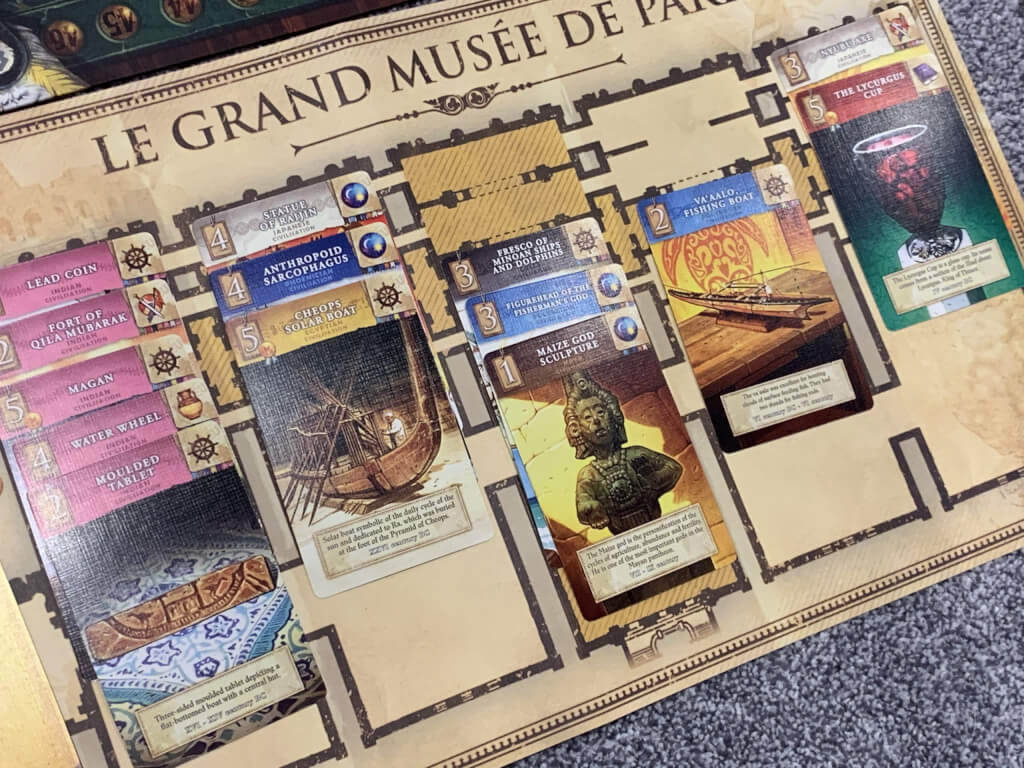

Without a doubt, the artwork in Museum deserves a special mention. The artist for the 300 plus cards featured here is Vincent Dutrait (famous for Alexandria, Atlantis Rising. The One Hundred Tori and many more) and each and everyone is superbly done. Not only is the artwork on these cards bright, detailed and thought-provoking, it is also backed by a strong colour scheme and very clear iconography that supports the mechanical aspects of the game.

In effect, it’s very simple to see what civilisation or domain (warfare, agriculture etc) each card belongs to, and the written text is also just interesting enough to whet the appetite – expect players to be visiting Wiki’s about these artefacts throughout the game. Whilst this does slow the first few games down, there’s a very strong educational aspect to Museum that should make it a legitimate prospect for parents looking to get children between the ages of about eight and fifteen or sixteen more focused on history.

Museum’s gameplay is crisp and simple, with each turn taking just a few minutes and the actions of drawing card, waiting for the other players to do the same if desired, and then furbishing the museum becoming second nature. There can be some slight delay here if players need to assess each other discard piles (which happens late on in the game) but the game mitigates this by enforcing a hand limit at the end of each turn, ultimately restricting the size that a discard pile might ever reach.

The more complex aspects of the game come in the form of scoring because the sets you might be seeking out to appease your patron will only count if you can place them in your museum in a connected, orthogonal way. As I mentioned earlier, this kind of sounds complicated, but it’s not, and cards can count in multiple sets if they intersect properly. The good news is that players are free to rearrange their museum more or less any time they like, and in particular, they will do so one last time before the final scoring.

Overall, Museum is a superb addition to any collection thanks to its incredible looks, straightforward gameplay and very engaging mechanics. This is, without doubt, my favourite set collection game and I am practically counting down the days until my own kids will be old enough to play it and understand the magic of some of the wonderful artefacts on display. This is, without doubt, my first “must own” of 2020 and as such, I recommend it to players of all abilities and all ages from about eight years and up.

You can purchase Museum on Amazon.

Comments are closed.