ELO Darkness — Lane warrior

Some games are built to be efficient, both in the way they work and the use of components. Whatever grand vision the designer might have, sometimes market factors like price point and shipping show their influence. Wood is replaced with cardboard and unnecessary extras are trimmed. However, where ELO Darkness is concerned, no corners have been cut whatsoever in realising the grand design.

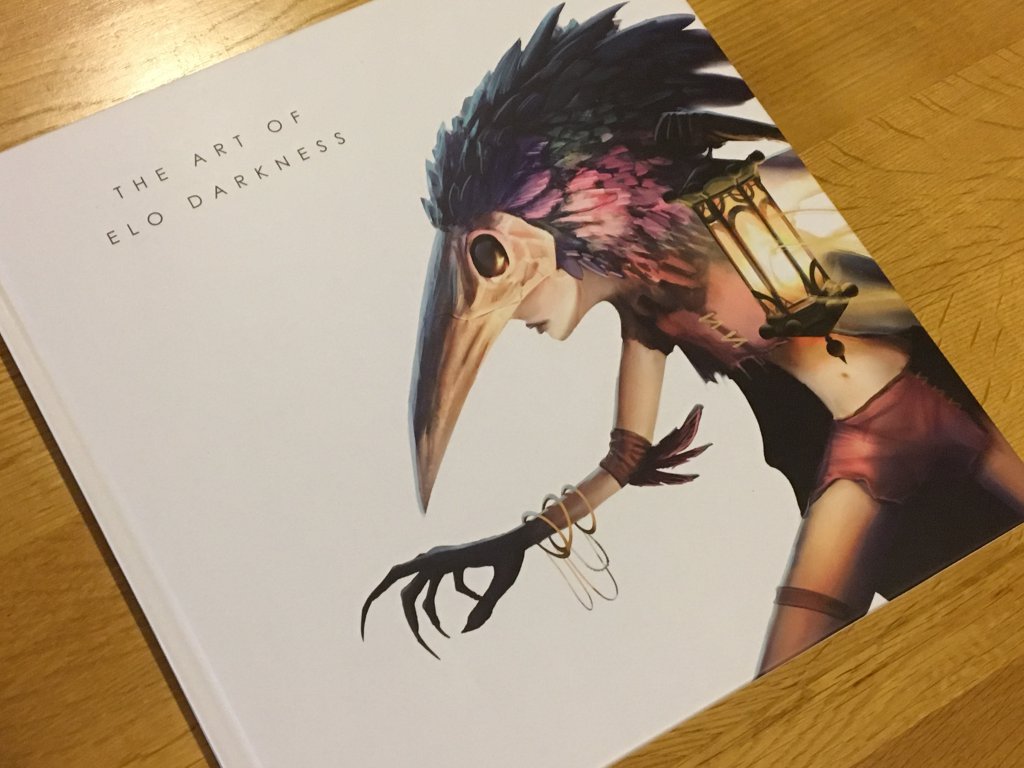

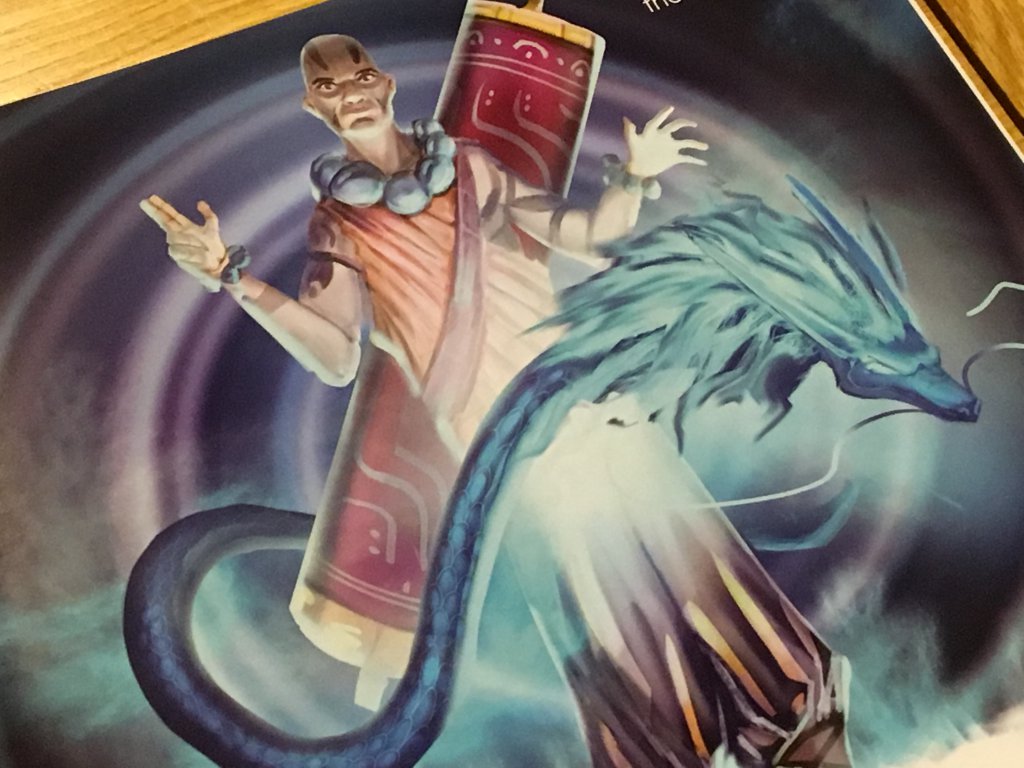

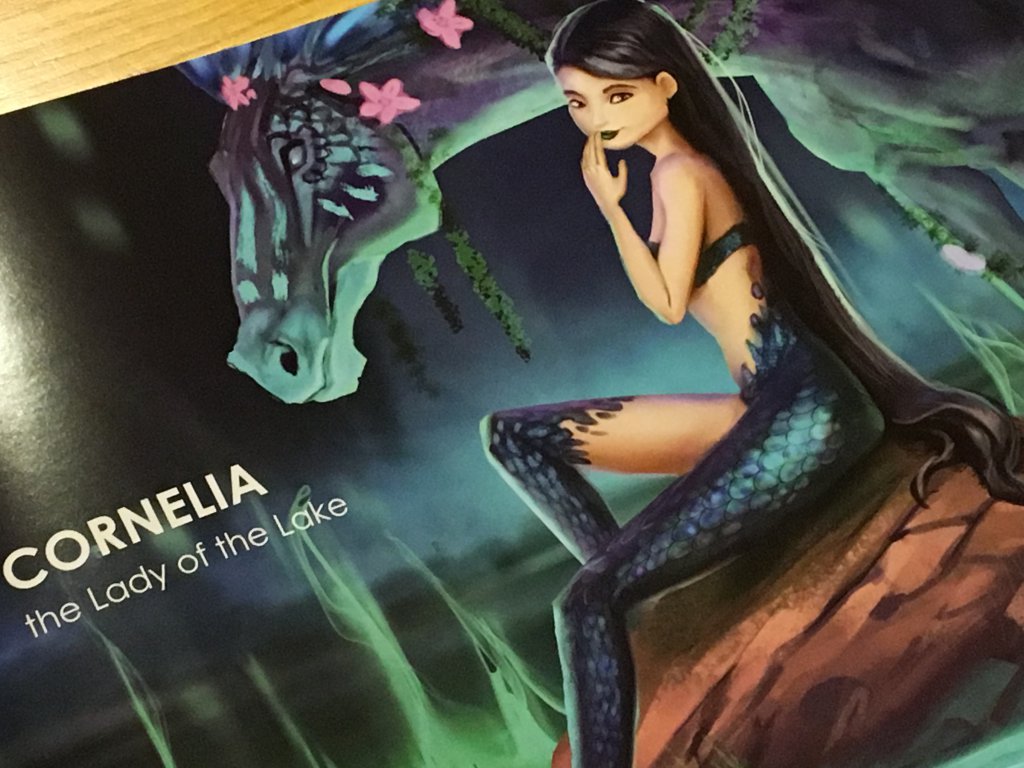

Love or hate the game itself, ELO Darkness is a tour de force in immersive lore, character design and production quality. I must concede that the version I have here for review is the Kickstarter Deluxe Edition, but it isn’t the plastic miniatures and art book that have left me with a lasting impression It’s the lavish artwork, the varied characters and the 500 plus cards that make up the decks in ELO Darkness. It’s the sheer majesty of opening the box and being faced with such a glorious standard of production.

But what is ELO Darkness and why should you care about it? In short, it’s a tabletop MOBA — also known in the video game world as a Multiplayer Online Battle Arena. Except, it’s not. Not really. Video game MOBA’s generally rely on the multiplayer element to enhance the experience. The players to face off against each other in teams of three or four on each side, and optimising the mix of characters to best effect is key.

The objective of each game of ELO Darkness is simply to drive the opposing player back in one of the three lanes, until finally you reach their base. At this point, the player who reaches the opponent’s base wins and the game ends. This is easier said than done of course, because players will be acting both strategically based on their chosen heroes and tactically in response to the changing board state and the status of each lane.

ELO Darkness, wisely, is designed predominantly as a two player game that uses a lot of the MOBA principles. It can be played solo or in teams of two players on each side, but in any configuration, each side will be made up of a team of five characters, representing different classes. Three of these characters are “Laners” and will focus on advancing the team up each of the three contested paths, whilst the other two act in support.

This is where ELO Darkness begins to show players hints of the depth that is contained within the base box — there is no Kickstarter exclusive content here in terms of characters, cards or core content. The base game contains… wait for it… fifty heroes, each with their own draft card, deck of base abilities and a couple of ultimate finishers. That’s 300 cards total. Add to that around 150 item cards and the same number of basic action cards — you have an incredible amount of content to wade through.

This is certainly daunting at first, until you realise that a fair bit of the content is repeated for both sides. The item deck and the basic abilities are duplicated for each side, whilst the heroes are split into five classes based on a colour coding system that makes them easy to manage. The players can use a pair of predetermined decks/sets of heroes for their first few games, but ELO Darkness is really intended to be played with either a draft variant or using player created decks, which requires a fair bit of knowledge and understanding to make the most of.

With so many cards, so many heroes and the relatively complex concept of a MOBA style game, ELO Darkness is a fairly complex but nonetheless logical game to play. A clearly defined turn structure helps the players get through their first few games, whilst the different combinations of heroes, basic action cards and items results in some powerful combinations. This gives ELO Darkness two distinct areas of focus — on the table, where each game unfolds, and off it, where players plan the best decks and experiment with different possibilities.

The designers at Reggie Games have done an exceptional job of reducing the onboard complexity by separating these two distinct areas. For example, each hero has access to two items, rather than the whole deck. This means that each side will have ten item cards in their deck, which can be bought at will. By restricting the decision about which item(s) can be purchased to two items per hero, the in game processing time is reduced.hilst there are fewer outlandish possibilities, the game is also kept balanced and focused.

Each game turn in ELO Darkness is split into three phases, known as Farming, Backing and Combat. When followed through from start to finish, the flow feels very logical on context of ELO Darkness’s ambition to replicate MOBA style play. In the farming phase, players have the option to discard hero cards in order to gain cards and/or gold, as indicated by symbols on the card.

When hero cards are discarded this way, the matching hero will gain an experience point which will ultimately increase their power in combat and enable them to use the higher level items. It is also during the farming phase that players can buy and sell items — there is a limit of three items in play at any time, so selling obsolete items at half face value is allowed. This is another mechanism that ensures the players only need to handle a limited number of rules at any given time, which I think is a sensible approach.

During the backing phase, the players may choose to retreat from a lane. When this happens, both players place a “Roaming” card on that lane, but the player who chose to back away loses one space on that lane. This is detrimental and moves them one space closer to a loss condition, but it also denies the opponent any of the benefits associated with making a challenge and winning on the same lane. Clearly, a design decision was made at Reggie Games to make this a key concept, because it’s simply not possible to defend all three lines all of the time.

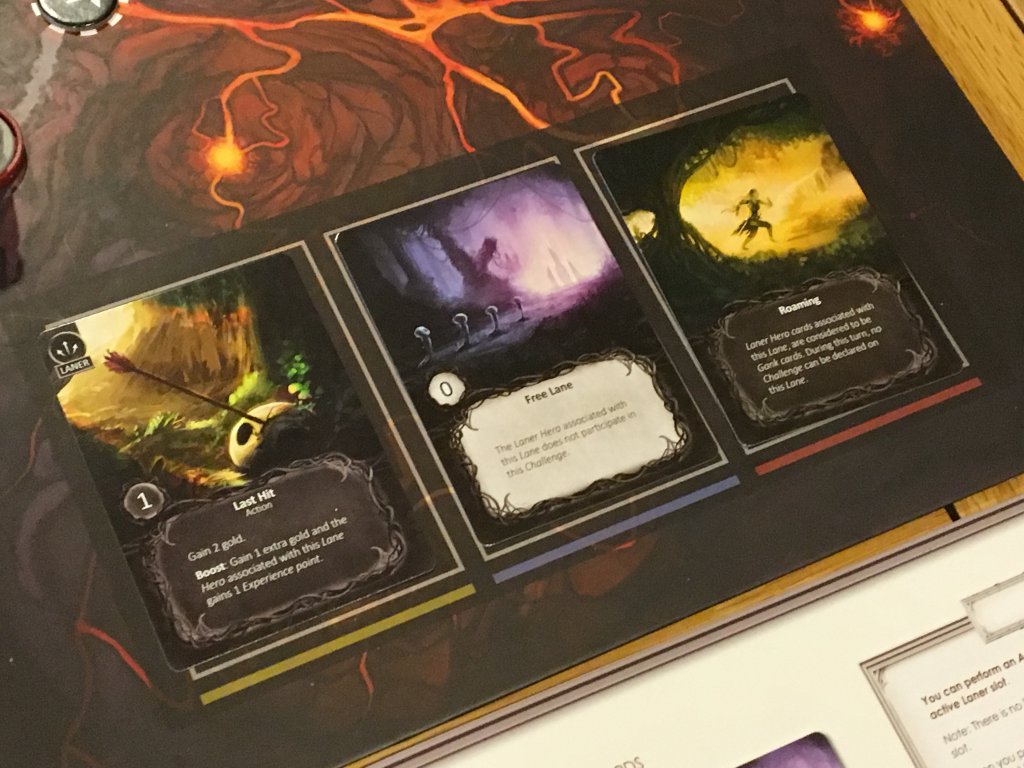

The final phase, combat, is split into two parts — deployment and challenge. During the deployment part of the turn, players choose cards to play into each of the lanes. Laner cards come in a few forms, but players will need to note that some are generic (and can be played into any lane) whilst others are specific and colour coded to a single lane, meaning that they can only affect that lane. One key benefit of backing out of a lane is that any laner cards associated with that lane and hero become jank cards, which I’ll explain shortly.

Players are also able to place a Free Lane card into their lane at this point, which will be beat by any other card, but is potentially better as a bluff than by backing, which absolutely, definitely moves that lane back one space. In short, backing results in a definite retreat but has some benefits, whereas Free Lane is still likely to result in losing ground, but can work as a bluff and will force a draw if both players do the same. Free Lane’s must also be played when a hero is defeated in a lane, on the turn that follows.

After deployment is complete, the board should have either a Roaming card (face up) or a face down deployed card on each side. When both players are satisfied, they flip up all the cards and the player with initiative chooses which conflict to resolve first. At this point, players take turns to play one of the five actions to increase their influence in the lane and ultimately win the challenge. Players can play gank cards (including the cards from laners who backed away), activate hero chains, activate items, take a greedy token or pass.

I won’t explain each of these actions in exhaustive detail, but to summarise, players will almost always trade one or more gank cards, since they represent support heroes joining the fray to support the lane. Activating a hero chain is less likely to happen, since it involves using a second card from the hero already in the lane. Getting greedy is harder to explain, but it basically allows a player to gain one influence in exchange for a threat token — to summarise threat tokens, they essentially make it much easier for a hero to die, which only happens when a sufficient influence deficit is met.

After both players pass, the challenge is resolved based on the difference between the cumulative influence values collected on each side. If a player completely wipes the floor with the opponent, then they may kill the hero, but usually, the winning player simply pushes the lane towards their opponent one space. All heroes participating gain one experience point and sometimes effects will be resolved. If a tower is destroyed this way, then the advancing player can draw a card or claim two gold. This process is repeated for each battle, with heroes who participated considered exhausted (and therefore unable to play cards in later battles.)

As noted earlier, ELO Darkness continues in more or less this way until one of the players reaches their opponents base and effectively captures it. Games can be quite variable in length, perhaps ranging between about an hour (including setup) and two hours or slightly more. This, I think, is to do with several factors — luck of the draw, relative player skill and the way the decks face off, which is kind of linked to the others.

ELO Darkness prides itself on its low reliance on luck based mechanics such as dice rolling. This leaves only the luck of the draw as a potential issue, but because players have relatively high levels of freedom to affect their hand during the farming phase and to a lesser extent by backing, I don’t see this as a major issue. I’d say that I’ve seen lanes lose one or two spaces (which is pretty bad, to be fair) as a result of bad cards, but even when a player fails to address their hand, they can still bluff with a Free Lane or back away and take the benefit, as above.

This focus on allowing the players to take full control of their destiny begins before the game starts however, and there’s no doubt that one of ELO Darkness’s key benefits is that it has a considerable deckbuilding element to it. Another strong feature is how it looks — which is frankly incredible. I haven’t seen better produced art, card stock or tokens in any game, ever, I don’t think. As a pure spectacle, ELO Darkness is just incredible.

Where it is less successful, I think, is in capturing the casual audience — and arguably that’s not who it is aimed at anyway. The level of pre and in-game immersion required is high and mistakes both in deckbuilding and during play are costly. Games that end due to one player making a couple of compounded mistakes feel disappointing for both players, with the winner (who is likely to be more experienced in this case) feeling like they have duped their friend.

The counter to this — production, pure volume of content etc aside — is that ELO Darkness is an incredible system that sings when played by two dedicated, experienced players. The to and fro of a well matched pair makes for an exciting game to be involved in and I could imagine that a well versed neutral observer would even be able to enjoy the technical intricacies of what was happening.

The build quality and incredible artwork, as well as the immersive, rewarding game make me feel that ELO Darkness is perfect for a fan of comic books or anime, and the game rewards players for repeated play. As such, I think a teenager with time to spare, or a player who has a relatively small collection and wants something with high replay value would love ELO Darkness. Personally, I admire ELO Darkness and I relish the chance to play it again, but I’ve learned to pick my opponents carefully and handle them with care until they can hold their own.

ELO Darkness by Reggie Games is available right now. You can find out more about it here.

Love board games? Check out our list of the top board games we’ve reviewed.

Comments are closed.