In service of The Greater Good

When a game hits almost every nail on the head, it doesn’t always matter what your preferences are — it’s going to make a splash. The Greater Good is one such game. Its stellar interweaving of audio, story and visuals make for a near-perfect combination. And it’s time to take a look.

The Greater Good’s world is one where magic is not only vanishing from the land, but has been outlawed, a step towards being ousted by man and machines. Your character exists right in the heart of the machine as a recruit in King Kro’s army, but you’re soon to find out that not everything is as clear-cut as first it seems. The story begins as you confront the leader of the Resistance, introducing itself in style…

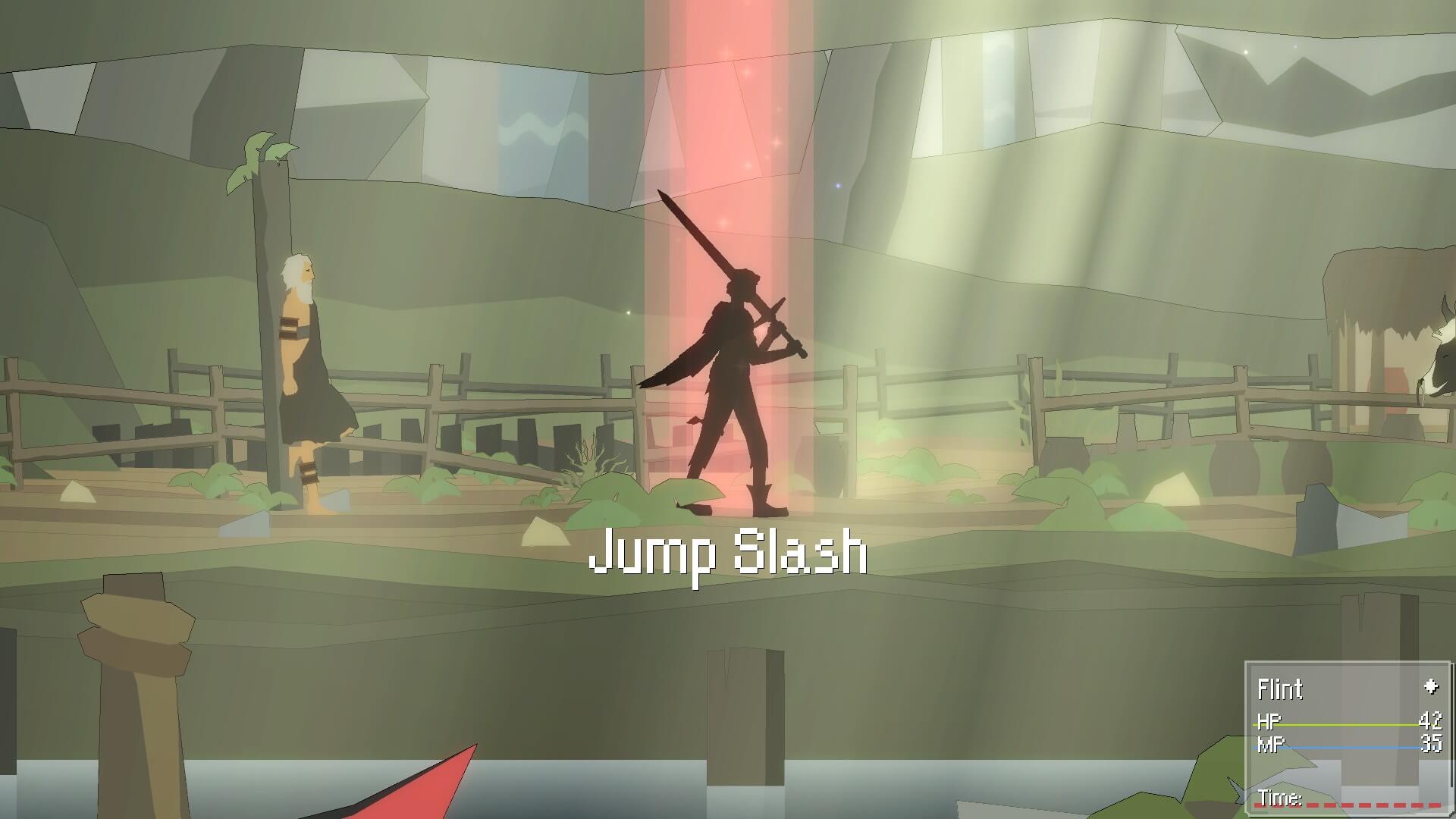

Style, in this case, means fabulous audio and artwork. The characters and landscape are picked out in sharp, flat-shaded 2D colour, edged by thin but noticeable lines that gives the impression it was drawn using the line tool in Paint, but to great effect. Light and dark play a spectacular role here. Characters sometimes turn to silhouettes in a darkened room or are obscured briefly by objects in the foreground. Always, the layers stretch from near to far, moving in parallax alongside you. The world feels alive, vibrant and bigger than you could possibly explore in three dimensions.

Music always accompanies this. In ordinary travel and combat, it’s pleasant to listen to. In cutscenes, it ties in perfectly with the key beats of the story. It’s not the music style we’d expect if we’d only seen the trailers on mute, but we wouldn’t replace it with anything else after playing it.

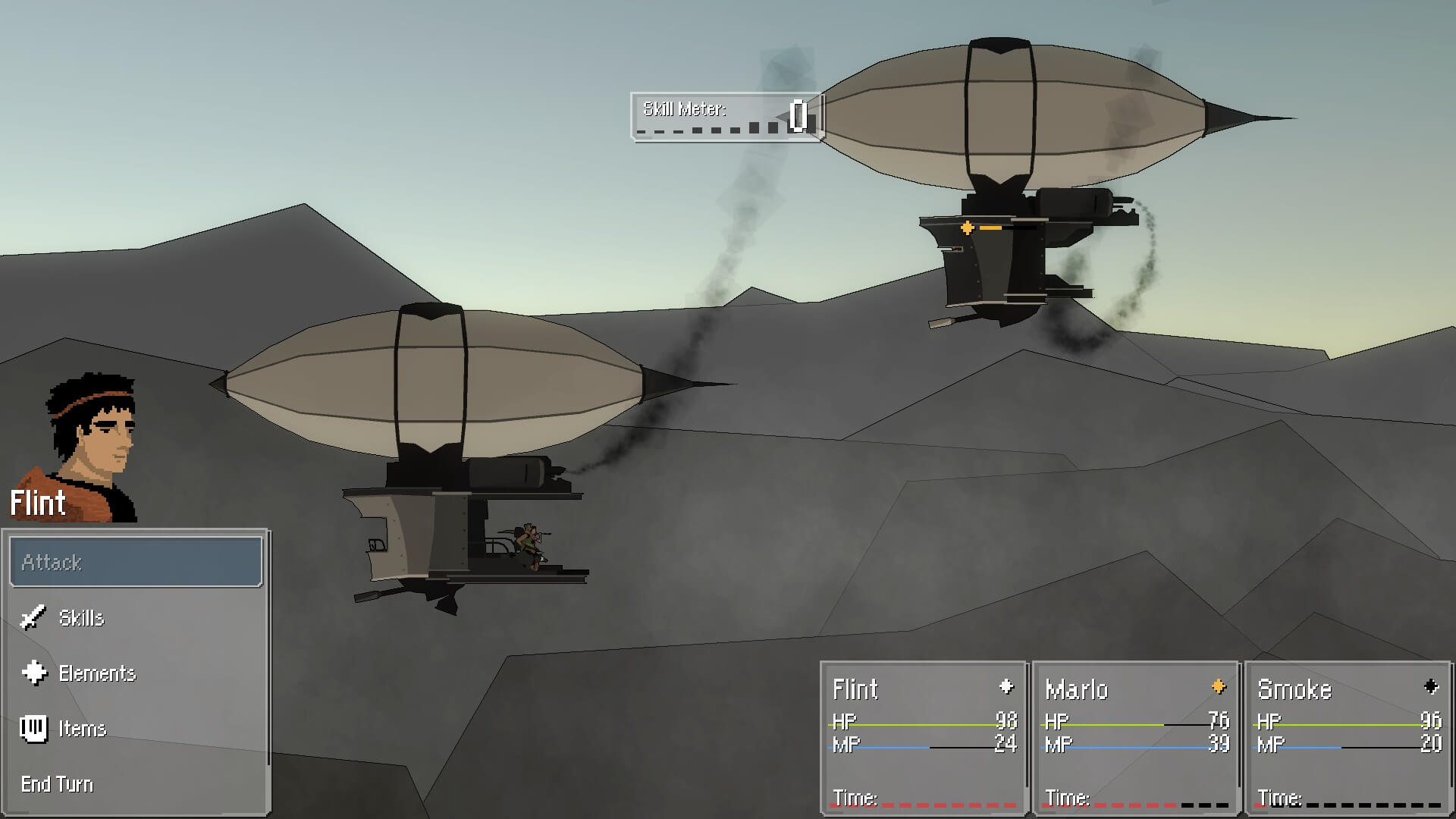

Combat is your semi-typical JRPG fare, where a cooldown system decides how frequently each character can attack. Having played The Greater Good for some time now, we’re still unsure exactly how this works. We think it builds up an initiative order based on when each meter fills up, but we’re not sure if that means being slow to react delays your next move for that character. For this reason we sometimes ended up picking options faster than the attack animations played out, preempting several turns ahead. A clearer indication at the beginning over exactly how to understand this system would have been useful. Still, it hasn’t caused us any major issues and shouldn’t be a stumbling block to new players.

In any case, combat itself has enough options to present you with tactical choices through the game. That amount of choice only ever seems too much if you’re worrying about being too slow — which, as we’ve mentioned, we’re not sure is even a problem.

Each character has a basic attack (ranged or melee), which is always limited to the attack of their preferred weapon type. They also have skills, which can have a variety of effects from attacking multiple enemies and scoring automatic criticals to scanning opponents’ health and stealing their held items. Then there’s the elements system, which grants access to characters’ elemental abilities at the cost of MP. Finally, of course, you have access to items to use in combat, which are largely alcohol-based. One of our fights certainly would have ended up with the entire party passed out from the amount they had to drink.

Skills can be very useful in a pinch, but your use of them is limited. Each costs a certain number of skill points, which fill up to a maximum of ten every time you make a physical attack. Learning to save your points for when you need them comes quickly, as you soon find that they persist between individual fights.

As for elements, you get access to one per character, with main character Flint wielding the healing powers of the lost light element. The powers grow with every level gained, adding more abilities to the list. Each element has a slightly different focus, but there’s a good range of spells in each one and you can give a character additional elemental abilities by equipping them with tomes, which also level up.

Our only criticism of the skills and elemental abilities is that they always start with the same animation with a different colour and pose for each character, mostly regardless of the skill they’re using. Making these shorter or combining them in some way with the animation that usually follows afterwards may have done something to make this less obvious.

The best thing is that you only do as much fighting as you want. It’s possible to avoid most enemies on the map (although we’d love to know if there’s a way to successfully dodge giraffes, as you can’t jump over them) just by jumping over them. At the same time, if you want to grind, you can grind. There’s no manual/auto save system, so you can only save at certain locations, but they also restore all your HP and MP, so you can keep going back to them. Some can be a bit spaced out, so it’s best to only move on from one if you know you have the time to make it to the next.

On the subject of travel, exploring the world of The Greater Good is a pleasure. There are plenty of hidden items around the map and they’re hidden in such interesting ways that the challenge of seeking them out becomes second nature — and you get to feel a bit smug once you’ve found one. The only downside is that your current objective is never stored anywhere, so if you come back to the game after a break or forget what a character said, you’ll have to scour the map for your next task (or do what we did and find the exact speech bubble from a selection of three YouTube videos, which still didn’t help until we realised we’d forgotten about the platforming’s verticality).

The only place where The Greater Good really could have done with more polish is in its control system and UI. There were only basic instructions for controls at the beginning and it took us a while to work out how to open the menu and inventory (shift, for those using keyboards, and backspace to navigate out). Until we found that, we’d been exiting the game by right-clicking its icon in the toolbar. An option to rebind the keys would be ideal, as a lot of them are not intuitively placed.

While the game does state right at the beginning that playing with a controller is highly recommended, most games that do this make it very clear on the Steam page — for transparency’s sake, it would have been nice for The Greater Good to do likewise.

All of that and we still haven’t mentioned the story. Well, we won’t say much in fear of spoilers, but it’s a damned good tale. Packed full of personality and well-timed humour, The Greater Good embeds story into every scene. It’s not something you forget as soon as you walk away from it. In some ways it is predictable, but that doesn’t stop it delivering its own twists along the way.

We mentioned at the beginning of this review that games hitting almost every nail on the head are practically guaranteed to make a splash. ‘Almost’ is the case here — in that there’s a small handful of things The Greater Good could improve, none of which drag it down too far. If you’re looking for an exciting new RPG experience with rewarding platforming exploration woven into its fantastically crafted levels… well, go and buy it now.

The Greater Good is currently available on PC.

Comments are closed.