Review | Torment: Tides of Numenera

Death is the only certain thing when it comes to life, and games have – since their advent – used different approaches to handling that inevitable, unenviable fate; from a simple game-over screen, through a full-restart with new character, to having you start anew as a younger generation.

Ultimately, most games with longer stories to tell will bring in more forgiving mechanics, or generous saving, in order to make sure that a wider-berth of players will make it through the game. This leads to behaviours like save-scumming (reloading to get a better outcome), or just a general disdain and lack of respect of the game’s difficulty.

Torment: Tides of Numenera (I’ll just call it Tides going forward), walks a fine line between balancing this, and encouraging curiousity, with it’s peculiar, fathoms-deep science fiction world. This is a game that has managed to make direct conflict nearly entirely avoidable, with various skill checks, or avoiding certain areas and conversation lines, able to get you out of smashing-and-bashing situations. In fact, my character has died about half-a-dozen times; and only once from combat – demons had crept from a mirror-world and shredded my team. My own fault, I hadn’t re-equipped weapons for three or four hours as I’d spent so long effectively avoiding conflict.

As my character awoke from their death, standing in the ‘labyrinth’, a construct within their mind, I found that several characters I’d met in the physical plane were there, and as such I’d gained more side-quests. There was no urge to reload, and re-do the fight.

As for my other deaths? They, in a strange way, were mostly deliberate. Letting a ghost rip out my throat, throwing myself off a cliff edge, and even allowing myself to be eaten alive by Dendra O’Hur; a cult who feast on corpses (they made an exception for me) to absorb the memories of their previous owners. Outside of the deliberate, some were what would be deemed in other games unfair, but the Tides setting – and obviously, the immortal protagonist – manages to strip back that unjustness.

Being immortal is, obviously, a rather generous boon to the character; however, it’s also an oddity in standard game design. Indeed, many games simply have your character’s motivation being to survive, or to pass X levels in one piece. As a matter of fact, this puts the game at a juxtaposition against many rogue-like, arcade, and survival titles, which simply strip back the entire goal of the game to ‘Don’t die’, or, to expand on that, ‘git loot, git good, don’t die’. Tides then, has the inverse of that; the need to create a game compelling enough to keep playing even though there’s no threat of campaign failure. The ‘big bad’ is a shadowy figure that you barely see, and rarely feel the presence of, out to hunt you down and destroy you due to the fact you are a discarded former host to a hero of the world turned eccentric by a lust for immortality.

I feel, from what I’ve seen so far, that it completely achieves that push forward despite this; and it’s due almost entirely to the depth and breath of the world that the Numenera system has allowed.

Well, it’s hard to put my finger precisely on one point that makes Tides excel at what it does. Setting, story, side-quests, characterisation, and attention to detail are all major players, as well as the fact that the game’s skill check system is a regularly at play -like the pen & paper setting it spins from.

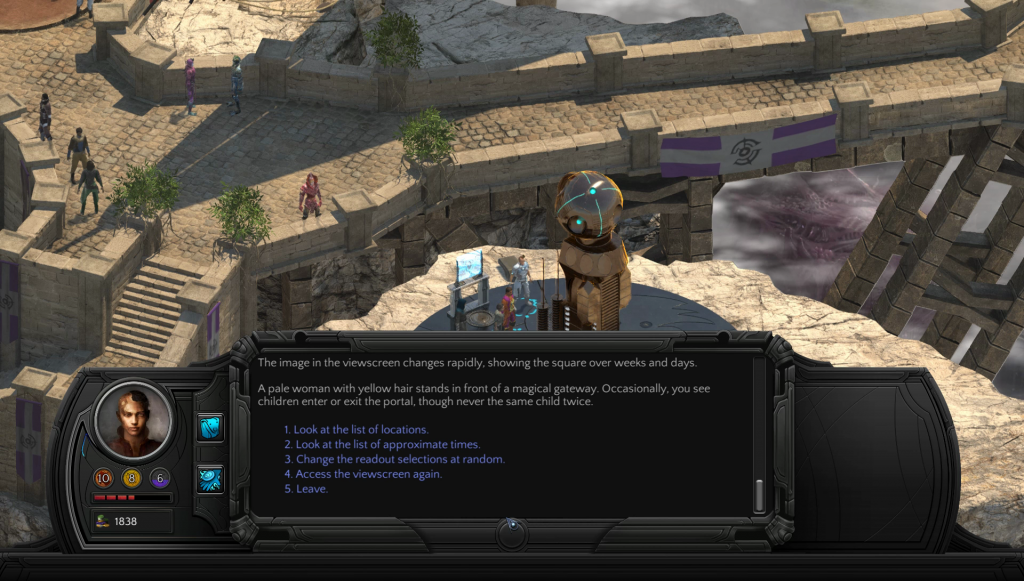

Arguably the setting is crucial to several of those; the Numenera setting -for those of you unaware- is one set on an Earth a billion years in the future. Society as we know it has collapsed, with everything we know completely lost to dust, tides, and time. An undefined amount of civilisations have risen and fell, with the more recent ones leaving visible marks on the world – the invading machines of a great war litter the land, built atop the ruins of the ages before; a giant creature, so large it is used as a trade hub, slowly creeps towards the ocean; the robotic builders of those who came before haunt the underbelly of ruins, eager to serve, or defend.

It’s undeniably tempting to fill ruins with malignant, evil beings, to make everything from an older race SO advanced that it is not just alien, but also nearly deadly; and this is really where the Numenera setting -which is essentially a low-magic fantasy setting with technology replacing magic- comes into its own. The whole pen & paper system is build around experience being a reward for resolving any situation; it proposes that you should be equally rewarded for unlocking a door as you would be smashing a skull, and also that should you smash a skull you’re not going to make many friends.

This means that the game shirks its CRPG counterparts’ dungeons for more social interactions, and it sheds it’s violent, instantly aggressive enemies for misunderstood creatures that you, the cast-off shell of a god, can -if you roll well, or have the right set-up- reason with.

As a matter of fact, the only times I’ve been thrown into the combat ‘crisis’ mode outside of the tutorial is when I’ve taken routes that I could have entirely avoided. In the first hub of the game this included; going in a place I’ve been told not to, trying to reason with demons, goading a hero to fight their greatest foe, and, well, going into a place I’ve been clearly told was very, very dangerous. And, my solution to the latter? After a few combat-end issues (the area, a reef-side building taken over by an AI, seemed to be the only place I had any technical issues) I simply sent my people out to avoid combat, and instead deactivate the opposing bots through purging the AI.

It’s worth noting that the re-branding of the moments when the game flicks to it’s turn-based system – one that, similar to modern XCOM, and many grid-based TBS titles, sees your turns split into a move and attack- from combat to crises are deliberate. The transition is nearly instant, and interactive elements of the environment take on new functions as map elements can be used against enemies, or -as in the example above- used to change the challenge to a skill-based one rather than a combat based one.

Combat itself runs off of the game’s stat system, with each character having three effort pools; speed, might & intellect. Within these pools you can have edges, which lock in a free point of effort for anything using the pool. Submitting additional effort to any action will increase it’s chance of success – be that hitting, or whatever is appropriate.

Esoteries, which are the game’s spells and abilities, are twists on traditional equivalents, although with a vastly simplified damage type system in place, with many ranged Esoteries giving the player a selection from all four magic damage types to deploy.

Then, of course, there are the Cyphers.

Cyphers are one shot items which have massive effects; the classic cRPG legendary items, but characterised by the setting. It’s always hard to decide when is the right time to crack open that crystal and deal massive critical damage to your enemy, or to use the cypher that boosts all of your lore abilities until your next rest. Each also comes with its own lore-filled description, all of them exceptionally well written, making them feel like a perfect fit in the odd, hodge-podge existence that is being chalked out in the ruins of what came before.

That said, almost every item in the game world is unique – rewards for quests, and looting are quirky relics in the form of oddities. A shiny gem, or family heirloom instead replaced with all sorts of wonderful creations that build on the world lore in their own way. Rather than a bland ‘This is an Opal’, you instead get half a dozen paragraphs on how the item works; shrinking an animal into a tiny size, letting you hear the words of a random other person on the planet. Tides is 100% a game for people with no fear of reading; the people who read all of the codex in Mass Effect, or who built up a library in Skyrim.

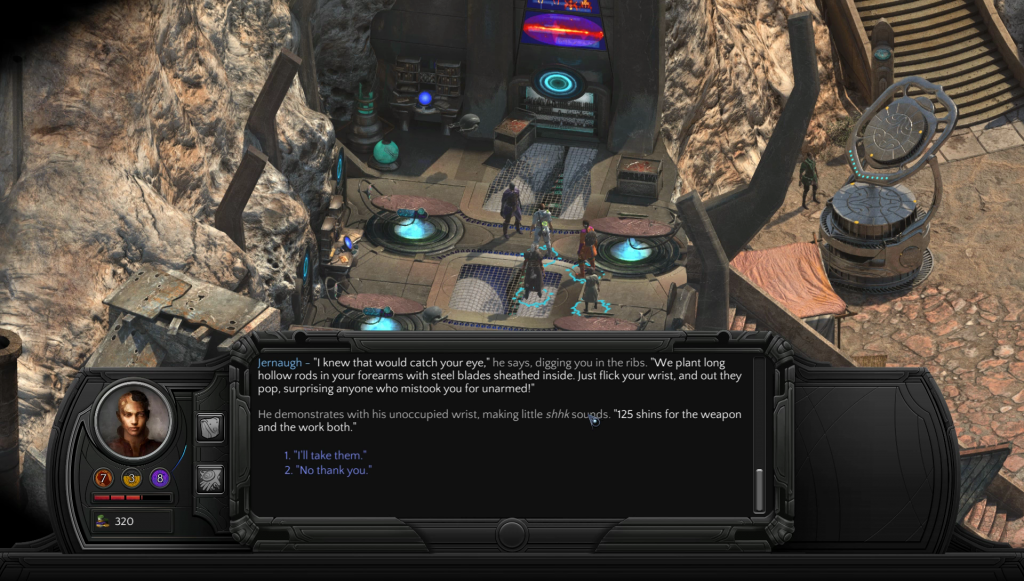

I’m a horder in most cRPGs, keeping a hold of anything of high value of potential use later in the game; this means that I’m the person who never uses potions because they might be more useful later. Tides’ characterisation of almost everything actually managed to shatter that. There’s little to spend money on if you’re thorough in the game; there’s a place where you can have major surgery to improve yourself – nanite blood, cool hidden-blades, an artificial eye. Aside from that however, many of the side-quest rewards are more powerful than the store-bought items, and so you’ll rarely be buying equipment.

No – my main spending was best done on buying restorative items, not necessarily potions, but instead the items that restored effort pools. These are, after-all, critical if you want to continue succeeding at skill checks. The effort pools, you see, only restore when you use curative items, or you rest, and resting advances time.

Advancing time, or simply repeat resting as to heal up, is not something that’s normally punished in games. I must have spent weeks in BGII’s starting dungeon as I rested and healed up after every encounter. In Tides however, time moving is almost always bad. An early quest sees a murder on the loose, and they will actively claim more victims as time passes, including a very likeable character. There’s also a companion who is tied to the time when you first meet them; a former colleague of theirs is being tortured, and may condemn the scoundrel (albeit, a likeable scoundrel) to death if allowed to die themselves (through the memory reading powers of the Dendra O’hua).

The scoundrel in question, Tybir, has remained a permanent fixture in my team, despite the fact that my protagonist has the ability to read minds, and so knows that the man, despite his ballsy attitude, is tortured by his past as a mercenary, and is confident that he’ll betray me before the journey’s end. An anti Yoshimo, if you will. Your party regularly interrupt (and even redirect) conversations with NPCs, and so mixing up your conversation between wise but bitter Monk, wanted assassin, mysterious child, anti-hero scoundrel, phase-shattered nano, and the others makes for very different play experiences.

Rather than a good-evil slider, Tides’ titular tides system grades actions instead on fame, passion, charity, thirst for knowledge and duty, each of these represented by different colours. When you lean more towards certain types of gameplay (you can have two dominant tides) it will reflect on the world. This means that if you play through asking lots of prying, technical questions, you’ll ultimately start receiving a more lore-heavy, in-depth string of responses from other characters as the game goes on.

Without the choice, and the breadth of detail that fills the world, the effort-pool system would just be another mechanic. Those two things, in answer to my earlier statement, are the things that make Tides such a great game; indeed, anyone with an aversion to reading in games had best avoid the title. However, anyone who likes their lore and detail thick, and their choices to have repercussions, should definitely consider picking up the game.

I feel you when it comes to hoarding 😀 I always feel that everything might become useful at some point. And I love to check all the places, chests etc. for artifacts. I haven’t played “Tides of Numenera” yet, that’s why I’m here. Just wanted to know if it’s worth it. I’m planning on buying it on G2A. Any suggestions on that? They seem to have good prices here: http://www.g2a.com/r/torment-tides-of-numenera-pc , though I never used it before…

Anyway, thanks for the review, it helped with my decision 🙂

It’s really good if you love your loot, and also if you like talking your way out of combat.

I’ve very mixed feelings with G2A, while the prices are good there’s been a lot of talk of the platform being used to sell on scammed copies. With no way to know if it’s just a resell, or if it’s a scammed copy I always feel a little dubious. But, that’s just me.

Thanks for the input, I appreciate it!