Review | Decisive Campaigns : Barbarossa

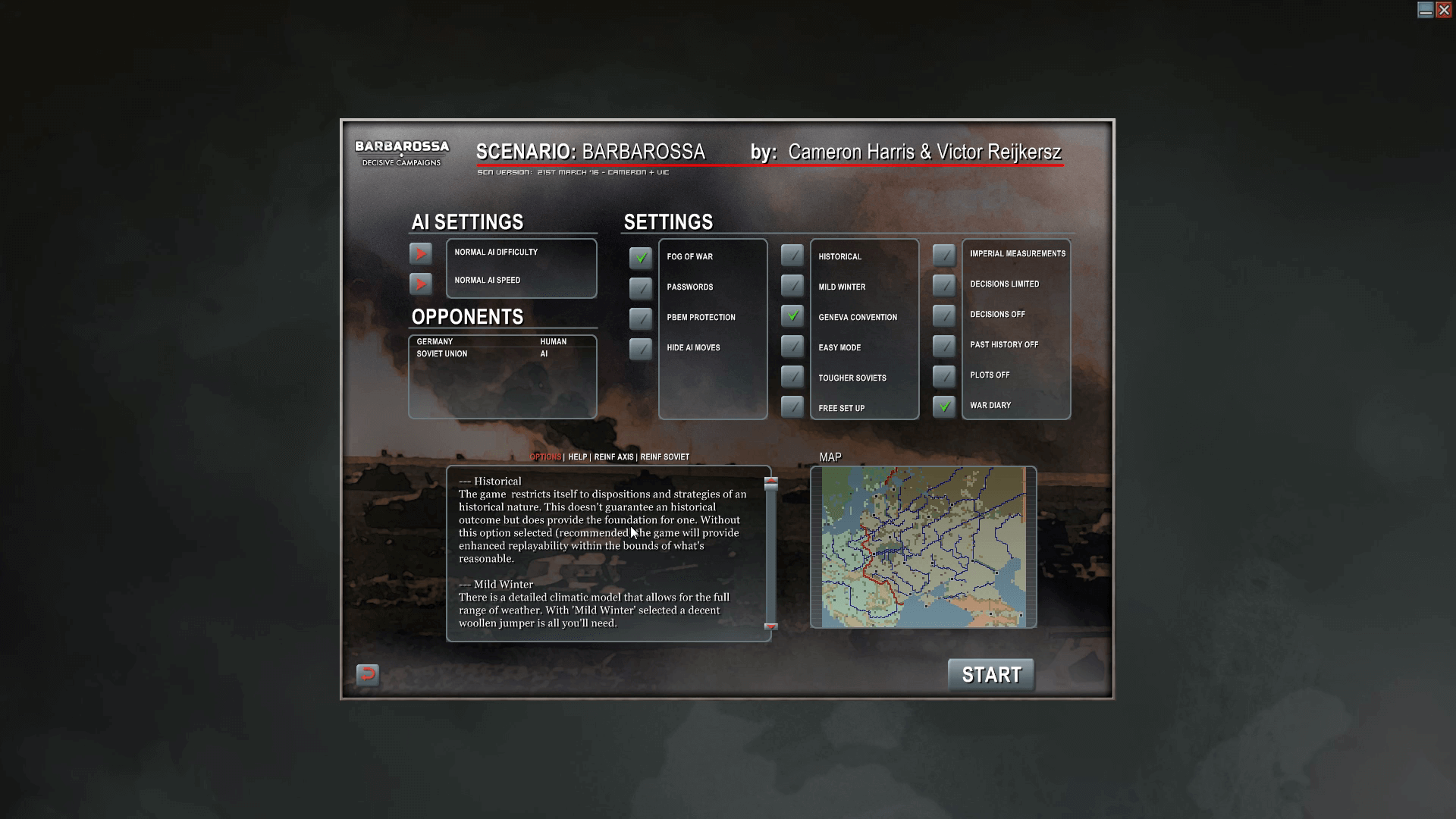

Late last year, on the 24th Nov, 2015, Decisive Campaigns: Barbarossa launched onto the Matrix store, it recently transferred to Steam, on the 29th of April, where it joined the two earlier entries in the series. As with those two, The Blitzkreig from Warsaw to Paris, and Case Blue, the series focuses on on fighting over wide fronts, and over a large scale. Barbarossa took that formula and added another layer, that of decisions and relationships.

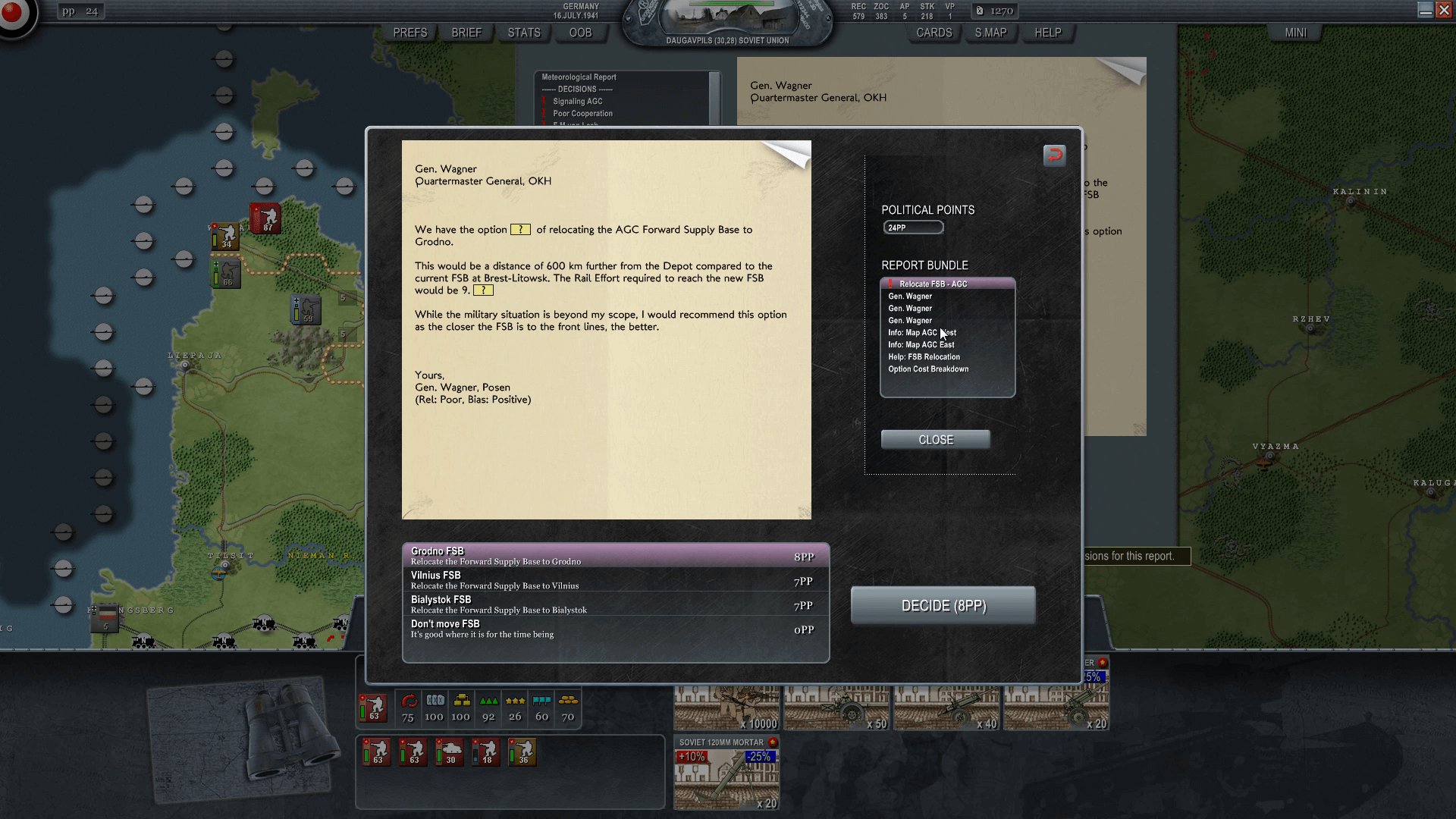

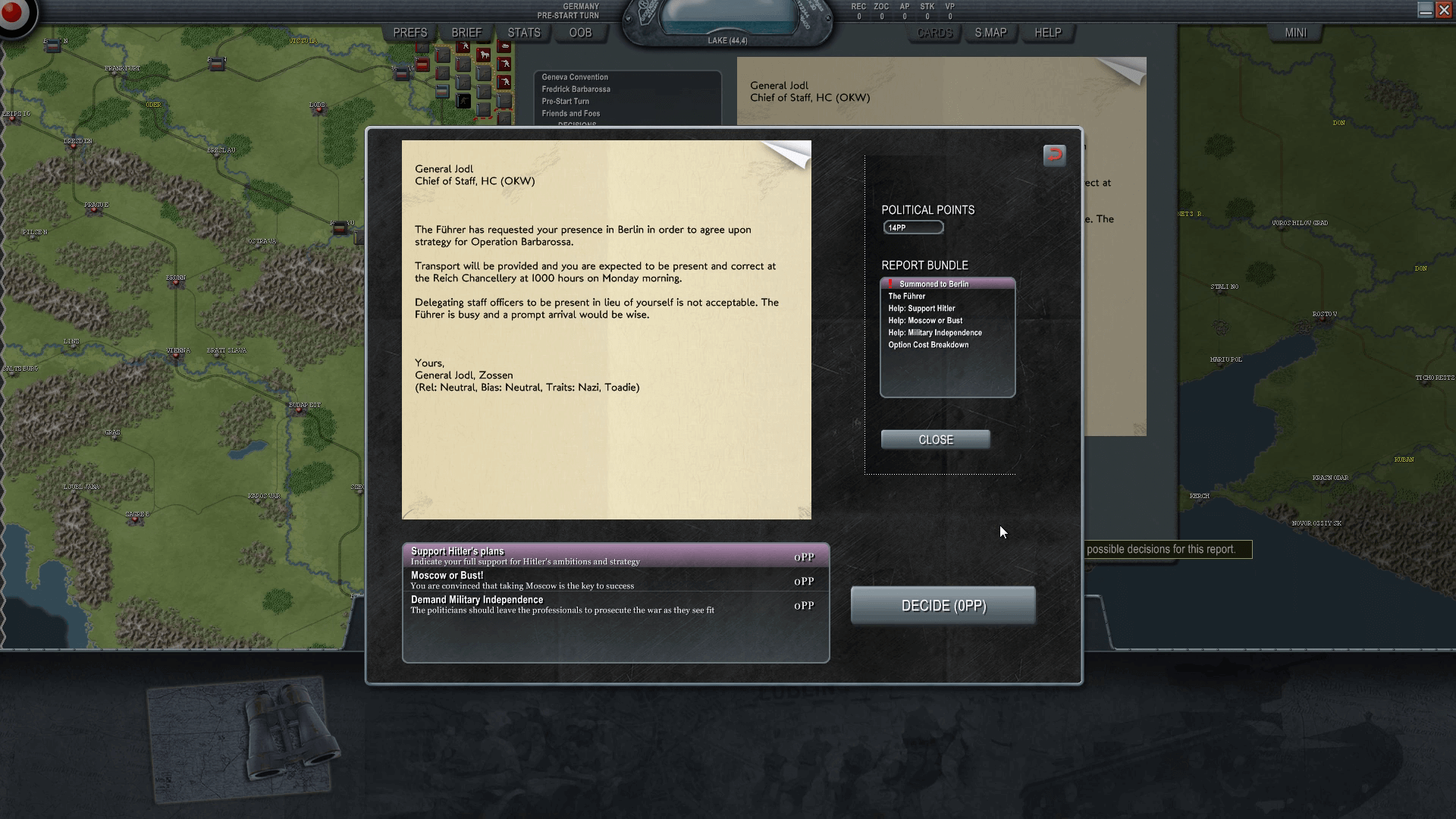

This new layer takes the four-day turns and card systems, and adds in events which trigger outside of any pre-set order. These events have multiple resolutions which then play out on the battlefield and also have effects on the various superiors, peers and field commanders of your forces. If you choose the German forces then you’ll be playing as Franz Halder, the competent chief of the OKH general staff who notoriously, historically did his best to avoid the politics that controlled the nation. If you choose the USSR however, you’ll be playing as Stalin himself – and rather than favours your relationships with your officers will be gauged through Stalin’s perception of their loyalty.

When I first watched the trailer for Barbarossa I actually thought the letters fluttering up towards the screen showing decisions for the various fronts were simply symbolic of a shifting set of objectives you would be working towards as Winter approached and the battlefront shifted. In fact it was probably one of the most fun innovations I’ve seen added to Wargames in my time covering them.

Quick History Lesson

Barbarossa, named after the iconic Frederick Barbarossa a medieval Holy Roman Emperor who was held in legendary regard as a charismatic, militarily able German ruler. A legend said that he slept, and one day he would awake and return Germany to its former greatness. Nazi Germany’s plan to unite the Eastern reaches of Europe under their reach included a large scale, three pronged charge into Russian territory by the name of Operation Fritz, prior to its activation however its name was changed to the now iconic, Operation Barbarossa. The operation would go on to be the largest military operation in history, with nearly 5million casualties as the highly trained – but unprepared for Winter – German forces charged into a nation whose military were still recovering from a great officer purge, but were to fight to the last soldier.

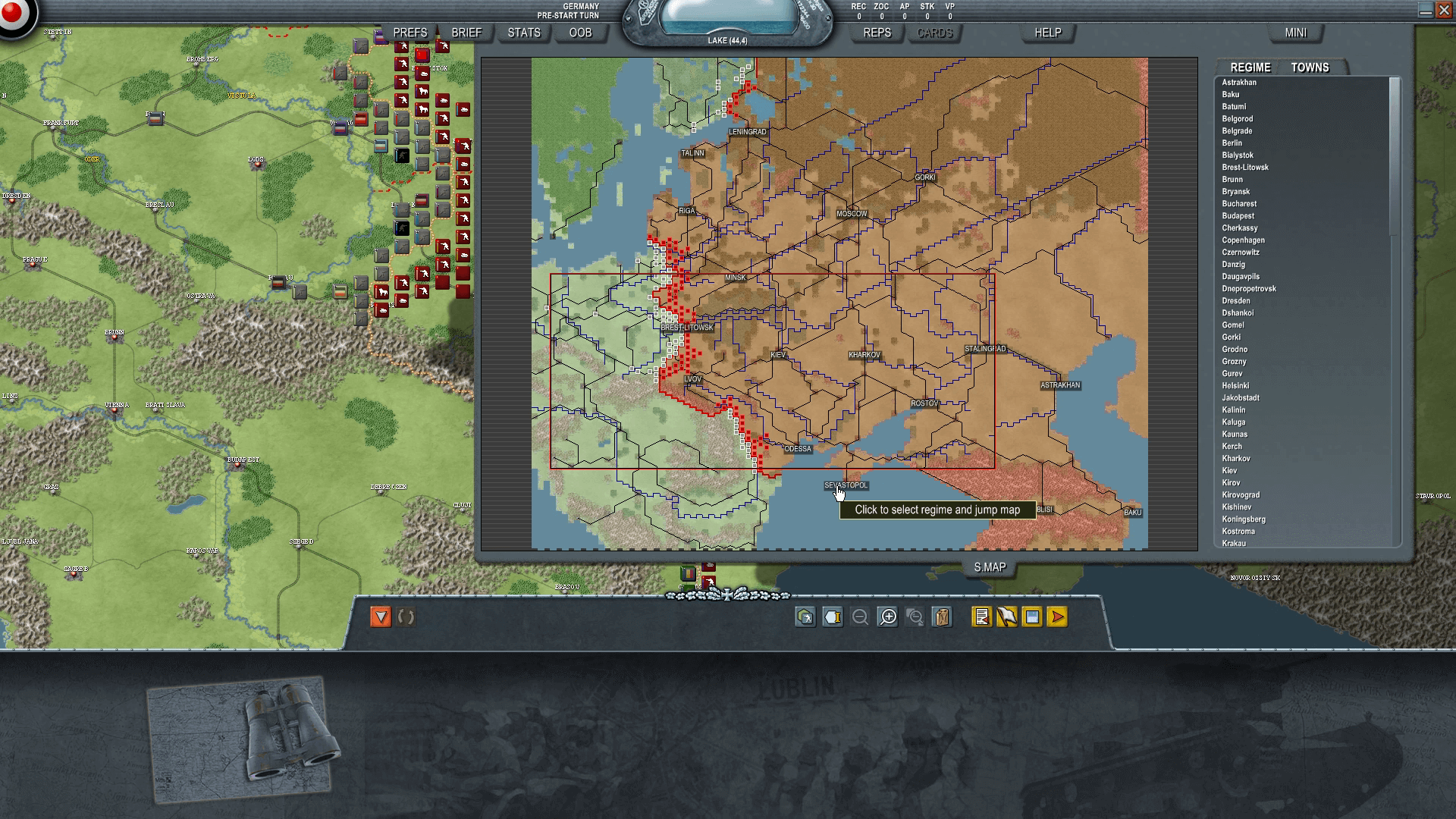

Underneath the decisions, which I’ll get back to later on, is a streamlined wargaming experience. While the deeper simulations tend to go the way of Advanced Squad Leader in featuring several phases of play within a single turn – Movement, supporting fire, defensive fire, attack, return volleys – the Decisive Campaigns engine strips this down to a battle tile by tile. What this means is that, in its purest form, a unit is only engaging a unit when a tile is contended. Now, these attacks are not simply restricted to one unit vs. one unit, during your turn you can commit as many adjacent units to attack a set tile as you wish, although the game does recommend the maximum amount of troops based on the flanks you are attacking the enemies from. Combat then plays out entirely through the numbers in the background, with several bars bounding about until the battle concludes.

Each of the units in the game are clearly displayed and, even at the various zoom levels you can get adequate information as to get a rough idea of the turn out of the battle. No single unit is a single head strong either, some will count into the hundreds, and the lowest I’ve seen through my several play-throughs are those representative of officers, who still move in stacks.

So, combat turns are extremely streamlined in regards to engagement and phases, as a matter of fact, movement is also, with most actions in the game being manageable entirely with the mouse, and only a few clicks required to initiate a move or a battle. This is especially worthy of celebration, as it all leads to a game wherein you can complete the scenario in a matter of a dozen hours as opposed to a dozen days.

This easy structure does work against it sometimes however, the sheer size of the battlefield and limitations on drawing out plans or marking units as units of interest, led to me having to crack out a pen and paper after several turns, as I had been deliberately setting up several large stacks of units to pass around the rear of a city while my core forces in that front captured it, but due to being distracted by the sheer amount of units under my direct command I had missed my opportunity. Had the game a layer with which I could make notes and mark out my plans then, well, I’d be singing from the hills. Another alternative would be the ability to delegate – there were ample times during my time as Halder where I wished I could have just left the Romanian forces, or even von Leeb in the North, to present options or even act on their own.

The unit selection and movement system – while easy – makes it dangerously easy to form large stacks of troops, simply moving them onto a tile will merge them into the forces there. This is great when you want to quickly form an offensive, however a keypress which could have you quickly cycle through units on the tile (rather than clicking on portraits) would have been welcome in the German campaign, as the ever widening fronts tended to demand a long army rather than a tall one. That said, it’s only a few more clicks to separate the troops out – it’s just a case of keeping that plan in mind for the next turn.

The game also features a really easy to understand supply lines system, and regularly touches on the infrastructure issues the German’s faced in their invasions. Each group of units has a unit which serves as their HQ, and each HQ falls under supply from the a forward operating base for that front front. Units are naturally more effective when they are kept in proximity to their HQ, and similarly the battle lines cannot accelerate too far, too fast, or the HQs will break supply and morale will falter. Moving up the supply points, and deciding on which route your forces will take through the USSR, is all managed by the decision system – if you commit your forces to convert a Russian rail network to German bore then you send your troops a different route then they will suffer for your inconsistencies.

There are, of course, elements that are out of your control by default. The three fronts are clearly divided on the map, and you’ll suffer major penalties for lending troops to combat our of their sphere. Hitler can be somewhat of an armchair general and can change the focus and objectives of the war as it goes on. Other officers will attempt to divert forces to themselves, and in-fighting or favouritism will rear its head more than once. Each of these points can be affected by decisions, or cards, which you use by expending power points – a rare commodity which you simply never have enough of.

Cards are a deck of major changes to your forces, be that switching a group to rest, calling in Luftwaffe reinforcements, moving troops between fronts, or even switching fronts between the three stances – blitz, offensive, defensive. The cards are best not forgotten, as resting will not just restore morale and limit losses, troops will bring tanks and vehicles back into operation, ensuring your forces retain their strength – albeit in exchange for a little momentum.

While I’ve barely mentioned them, the Soviets are playable also. The relationships mechanic is changed up instead into a system based around perceived threat, and managing Stalin’s paranoia. Having purged the majority of the competent officers in the years prior to the war he is left with a bunch of former war comrades, brown-nosers, and luckless associates to fill out his ranks.

These troops have a clearly displayed (low) level of competence which dictates when they spring to arms in defense of the nation. The higher the level the more likely they are to pass the die roll and set their troops to action, however they are also likely to be deemed suspicious by Stalin.

This paranoia can be contained by using cards to send your enforcers, Krushchev & Zhukov, to scare people into loyalty, or activate troops in the absence of good die rolls. However, as it is not a short war, there’s as close to guaranteed as-can-be chance that Josef will suffer a breakdown and send for the arrest of one of his officers, having them dragged off, shot, and replaced with another potential schemer.

There’s an amazing depth to the database of information in the game, should you wish to read into it. Details on each unit are fully visible, units can be called to report in, each unit tracks its mileage since service, and how its supplies are holding up. Even the various, historic, officers have database files on them which expand on their fates, and explain the personality patterns you might notice developing after several games.

While there is only one scenario in the game, the fact that the decisions in the game are different each time, and the AI is smart – actively encircling and withdrawing – means that Barbarossa has a lot more to offer beyond a single play of each nation. It’s a game I’ll definitely return to – and I look forward to the next Decisive Campaigns game with bated breath.

Comments are closed.