Nagaraja is a head to head Temple of Doom simulator

Every once in a while, a board game comes along which is almost completely unique. For better or worse, there’s little I enjoy more than exploring new systems, components and mechanics. Having begun playing Nagaraja without any expectation or understanding of what it offered, how would you feel if I told you it was a head to head, card driven, dice rolling, temple building relic collection game? Intrigued, I’d hope!

Cramming so much into such a small and relatively straightforward game is nothing short of miraculous, and despite an awful lot going on, Nagaraja really is over and done with in its stated half hour or so playtime. The length of each game is partly because the player count is restricted to just two, making Nagaraja not only fast paced, but also fiercely competitive.

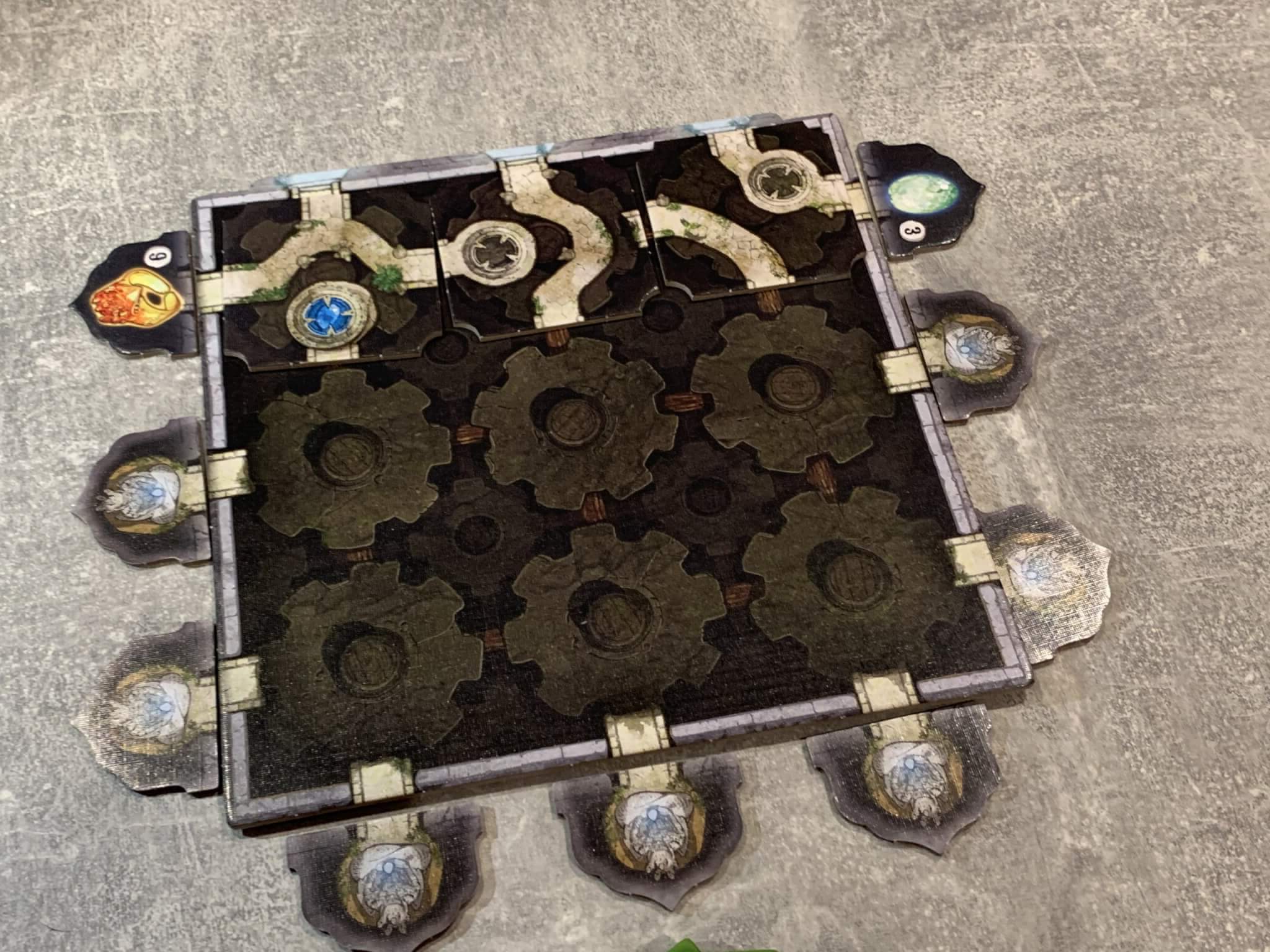

Each player is competing to score just twenty five points from the relics that surround their temple board. These relics (placed face down at each of nine exits) will have between three and six points printed on them, but three of them — the six point ones — are cursed. If at any point a player has all three cursed relics revealed, they will immediately lose the game.

Each player has their own temple board and its own set of relics, and these will only be revealed when a player has placed tiles into their temple that form a complete path from one of the three entrances. Each temple is arranged in a three by three grid, so at most it will take nine tiles to fill one, but in fact, using that many tiles is almost never necessary to reach the twenty five point target.

To obtain these tiles, the players compete by playing their cards over the three phases of each turn. The first phase focuses solely on card play, with the players placing the card (or cards, which must all have matching symbols) they wish to play face down in front of them. Whilst it is mandatory that the number of cards being played is shown, it’s fine to bluff or cajole your opponent about what you are playing.

These initial cards will serve only to determine how many of the “dice” will be claimed by each player. There are brown, white and green “dice” which are not actually dice at all, but I have no better word for them until I explain what they actually are. They are actually “Fate Sticks” according to the manual, and each one has fate points and/or serpents (naga) printed on their sides.

The brown Fate Sticks show only points, whilst the white ones have one three sides showing points and one showing a naga. The green sticks give a fifty percent chance of either outcome. The reason why you’ll want to prioritise one or the other relates to the two main phases of the turn, the first of which is further card play.

Taking it in turns beginning with the current first player, the players may spend one naga to use a card from their hand. When they do so, instead of playing the card for its fate stick generating capabilities, this method activates a second action at the bottom of the card. These actions do things such as adding fate points, allow a tile to be rotated, or enable a player to look at face down relics before replacing them face down again.

The really juicy bit of Nagaraja is in how these abilities may (often) allow a player to affect their opponents temple. You may swap a safe, face up relic for one that you previously peaked at and known to be cursed, for example, or you might even move their tiles around or reorder them. You may, if you feel especially mean, place the dreaded trap tile into their temple — which wastes a whole space.

Once the players have either ran out of cards or naga, or simply finished their shenanigans for the turn, the third and final phase of the turn commences. This simply involves the player who has the most fate points (on dice and cards played) taking the current face up tile (which may also have a hidden amulet on it) and placing it into their temple. If this new tile enables a clear path from any entrance to any relic, that relic will be flipped up. Similarly, if an amulet on a card has a path to it, it will also be revealed to the player who claimed it.

Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, the player who does not win the tile becomes the new first player and draws up three cards from the deck. They then assess those cards, keep two and give the third to their opponent. This incredibly simple mechanic works superbly in a head to head game and it absolutely ensures that neither player can easily run away with the game.

In honesty, I am almost at a loss for words when it comes to describing my experience with Nagaraja. Personally, it has rapidly become one of my favourite two player games thanks to its blend of clever mechanics (that give agency) and the presence of luck (in the card draws, the location of the relics and the rolling of fate sticks) and because it is incredibly competitive.

Sadly, of the five people that I’ve played it with, two really disliked it, which gives it about a 66 percent hit rate. When I asked them why, one said that it was because it’s just too directly competitive for them, whilst the other said that they couldn’t really get their head around what they were supposed to do — as if it didn’t really click. I live in hope that I can change their mind!

Thinking objectively about it, I can see why some people would rail against the competitive nature of Nagaraja, but if you look at it as something like Chess or Draughts, then that kind of confrontation has existed in almost every game for many centuries and it doesn’t seem to be a problem. The problem seems to be that when luck is involved in the outcome, even when there are ways to mitigate it, it makes people feel cheated or frustrated.

The other four players (I’m including myself to make a total of six) found Nagaraja incredibly fun and very, very exciting. I love the look of the game, the way the different mechanics integrate seamlessly and the competitive nature of things. I love how a player might be close to victory, only to have it snatched away by the other player rotating their tiles and closing off access to a key relic, or better still, when a third cursed relic is uncovered to result in an outright loss.

There’s no doubt that Nagaraja can get very, very nasty, but the fact that each game is so quick to set up or reset, and that the game itself only takes about half an hour takes the edge of that. Luck can play a factor and that means that the players shouldn’t take it too seriously, but then with the amount of agency that the cards give, it can frustrate when just one or two draws or rolls don’t go your way (given that everything else feels within your grasp).

I can’t think of tons of modern board games that are strictly focused on the two player experience, although clearly they do exist. At any player count, few games are as unique and features such tightly entwined systems — almost like the titular King of Snakes — as Nagaraja does. This game, whilst a little bit marmite, is one of the most unusual in my collection, and it’s a game that I will look forward to playing time again whenever I have the chance.

You can purchase Nagaraja on Amazon.

Love board games? Check out our list of the top board games we’ve reviewed.

Comments are closed.